Comes from https://onlybook.es/blog/saul-steinberg-artista/

«This translation from Spanish (the original text) to English is not professional. I used Google Translate, so there may be linguistic errors that I ask you to overlook. I have often been asked to share my texts in English, which is why I decided to try. I appreciate your patience, and if you see anything that can be improved and would like to let me know, I would be grateful. In the meantime, with all its imperfections, here are the lines I have written». Hugo Kliczkowski Juritz

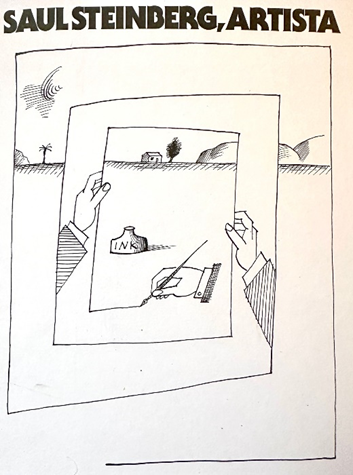

If this book is titled «Saul Steinberg, artist» it is because it states, from beginning to end, that this was the most radical vocation of the man who said of himself that he had not just «belonged to the world of art, cartoons or drawing.» and that the art world didn’t know where to place it. Profusely illustrated, it covers his life and work in Europe and the United States of America, especially in New York.

Saul Steinderg: The Wandering Sign

Alicia Chillida (1)

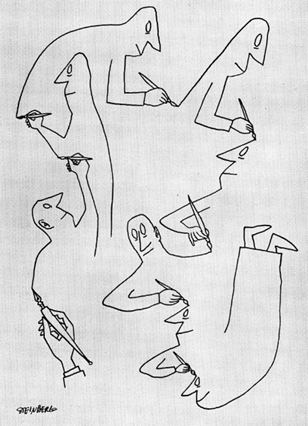

«I am a writer who draws.» Saul Steinberg

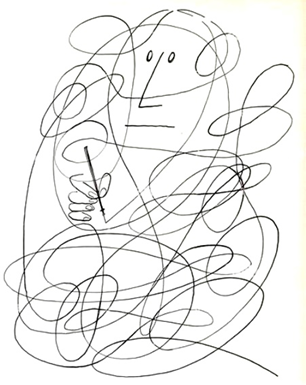

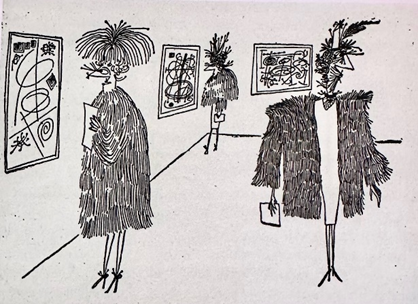

The paper on which Saul Steinberg draws seems to transform into a continuous and infinite ribbon. With its profuse lines it is capable of invading territories, maps, art galleries, museums, people, furniture, animals or buildings. (…)

Origin and Destination

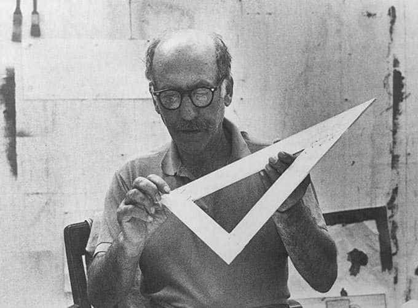

Saul Steinberg chose drawing in search of maximum freedom of expression and action, until it became a wandering sign, traced by its own existence. He was born in 1914 in Râmnicu Sărat, a Romanian town near Bucharest, into a Jewish family of Russian descent who emigrated to the capital in 1915. He studied Philosophy and Letters at the University of Bucharest. Between 1933 and 1940 he lived in Milan, and there he obtained a degree in Architecture from the Royal Polytechnic. A tireless draftsman, inspired by Cubism and the Bauhaus, he began working in 1936 for the satirical newspaper Bertoldo.

New York. 1966

As he himself would recall years later in his interview with Jean Vanden Heuvel (Los Angeles 1934 – 2017 New York), «although I believed that I did not have great talent, I always felt a strong inclination for drawing.»

When his first work was published he said, “I stared at it for hours, mesmerized. I walked carefully along each of the lines. It was probably not the drawing that I admired, but myself!

From that first publication, he became aware of the potential of his work and the power of disseminating his thoughts on paper through the mass media.

In the opinion of the American critic and philosopher Harold Rosenberg (New York 1906 – 1978 Springs), the author anticipated the artistic spirit of his time:

Steinberg, by capturing the mix (that exists) between nature and art, between the artist and the viewer, participates in the advanced artistic thinking of his time. Twenty years before pop art, he exposed his premises in a large number of drawings, as well as in the double relationship he maintains between commercial art and the museum.

In Italy, the architect and draftsman was a victim of Mussolini’s racial laws of 1938, which prohibited him from practicing his profession as a draftsman. Arrested later, he was interned in the Tortoreto camp, from which he was allowed to leave on the condition that he leave the country. Years later, he would write to his friend Aldo Buzzi: «I seemed to be in someone else’s role, I saw myself as if I were someone else, something similar to the situation of a man who draws a man.»

Finally, in 1941, he managed to flee Europe towards New York. He had to wait about a year in the Dominican Republic – where he met the Spanish painter and poet Eugenio Granell – waiting to obtain a visa to enter the United States. During that period, he began to collaborate with the weekly newspaper The New Yorker, a fact that helped him, together with the mediation of his agent Cesare Civita and his relatives residing there, to enter the country in July 1942.

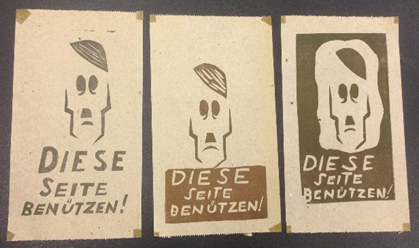

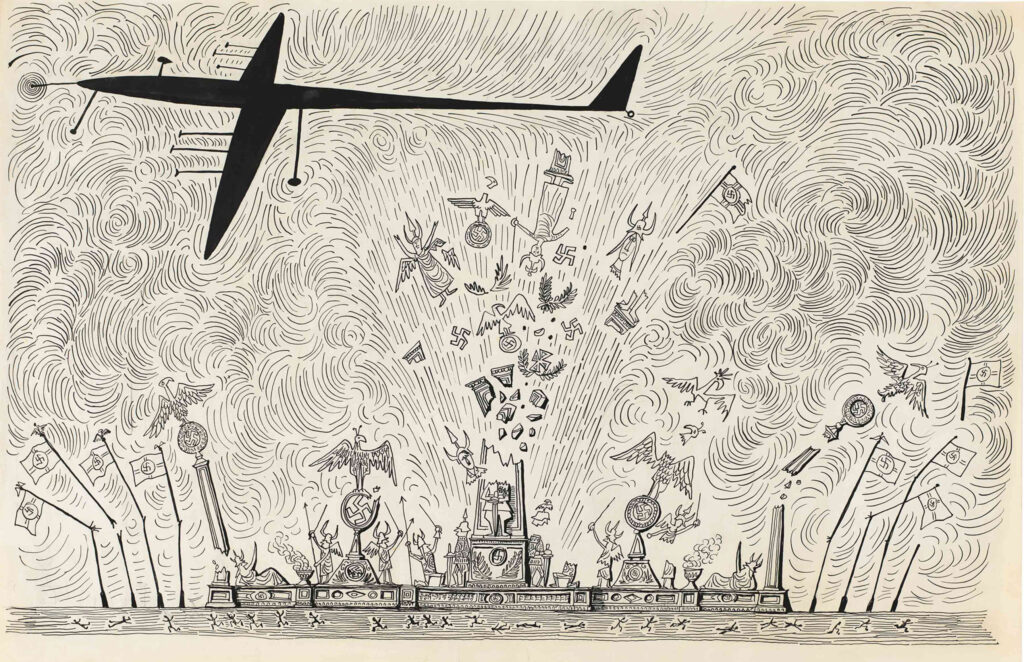

In 1942, still in Ciudad Trujillo (today Santo Domingo), he drew caricatures of Hitler that appeared in various publications and were part of the exhibition “Cartoons against the Axis,” organized by the American Society of Magazine Cartoonists and held at the Art Students. League, which also featured, among others, Ad Reinhardt, Crockett Johnson and Charles Addams.

Der Schuldige (The Guilty One), in the July 26, 1944 edition of Das Neue Deutschland, a fake Resistance newspaper produced by the OSS Moral Operations

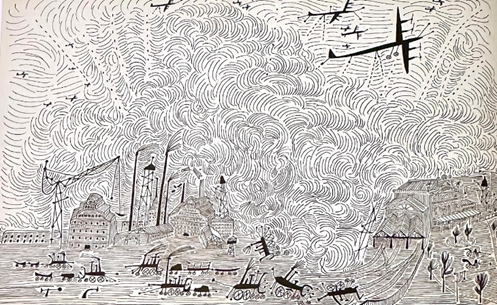

Already established in the United States, he was recruited in 1943 by the North American Naval Reserve and performed military service during World War II in the Moral Operations Division, integrated into the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

In this unit, he dedicated himself to producing material for psychological warfare against the Axis Powers and, for this purpose, he was sent to India, China, North Africa and Italy.

and instructions «Use this side»

In the fall of 1944, he settled permanently in New York, where he married the painter Hedda Sterne (Bucharest, 1910-New York, 2011).

After the war, he got to know the United States in depth and spent time in Europe, especially in Paris, where Romanian artists and writers who were part of the European intellectual and cultural elite such as Constantin Brancusi, Emil Cioran and Eugene Lonesco resided.

In 1957, he also traveled to Spain with his wife (and they visited San Sebastián, Madrid, Granada…). Among all these trips, it is worth mentioning the visit in 1958 to Picasso at his villa La Californie, in Cannes, where they had fun drawing exquisite corpses. (2)

A tireless explorer, he valued travel as a method. It would seem that in his drive to travel there was a desire for existential mutation, a desire to test himself and, perhaps, to become another. He was a wanderer due to his biography: Jewish, draftsman trained as an architect, prisoner and emigrant.

This tangled vital line is what draws its character and gives rise to the sign: a sign that moves between signs. Critic and art historian Dore Ashton has pointed out precisely this wandering condition of ST, in which character is destiny: Steinberg’s destiny was to identify the exact line among millions of possible lines to express his own character, simultaneously, with that of what he observed.

He knew that the word was derived from the ancient Greeks and that it was meant to engrave. For the Greeks, character was an instrument. For Steinberg, too.

Similarly, the French structuralist philosopher Roland Barthes, who dedicated an important essay to ST’s work, All except you, used the term «idiolect» to describe the characteristic way of speaking of this creator of sign-figures. .

The artist, according to Barthes, plays with all forms of representation, goes through the common language to create a new one, in which drawing becomes a way of philosophizing or satirizing, causing in the “reader” an intellectual spark, a grimace of laughter and despair.

ST offers a reading that never ends. From sign to sign, it invites the reader on an always unfinished journey.

New York, The Museum, Criticism, Art

Without ceasing to be present in magazines such as The New Yorker – which provided him with a collaboration that spanned more than five decades and allowed him to become known worldwide, or Flair, where he published his first photographic works during the 1950s – white photographs. and black intervened with drawing, which represents domestic interiors and urban scenes; In 1946 he participated in his first national exhibition: Fourteen Americans, curated by Dorothy C. Miller at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), along with artists such as Isamu Noguchi, Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell and Mark Tobey.

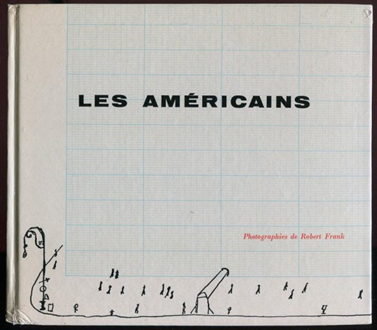

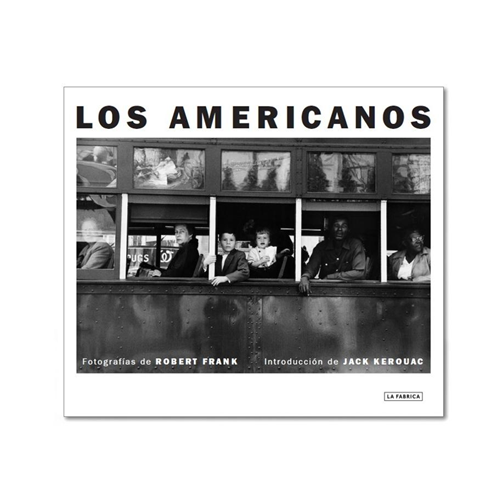

In 1958 the book “Les Américains” – The Americans – was published with photographs by Robert Frank, a Swiss emigrant of Jewish origin who had toured the United States between 1955 and 1956, portraying the streets, the faces of the people, the squares, the bars and shops. (3)

Robert Delpire, its Parisian editor, invited Saul Steinberg to make the cover of this first edition, who responded to the commission with a few strokes of black ink on millimeter paper, a drawing that condensed the spirit of New York in the 1950s. .

The extraordinary visual acuity with which ST observed his adopted country dialogues with the work of Robert Frank, both European artists, inveterate travelers and passionate chroniclers of North American society. Les Américains soon became one of the most influential photography books in the world.

The large train stations and buildings of the city constitute another motif captured by the draftsman-architect and wandering traveler, who loved his adopted continent while satirizing it:

Ah! I love America […]. Freedom of movement, freedom to be what you want. America is utopia! There are no social classes, no obligations… And what I also like about there is that everything happens quickly! The containers are always full, you can find grand pianos, last year’s televisions or sofas: it is the wealth of garbage in America. Another thing: you can be alone. If you die, no one notices.[… ] His inclusion in the aforementioned MoMA exhibition established him as one of the artists of the moment, which aroused the distrust of the American critic, Clement Greenberg. “The presence of artists such as Sharrer, the ineffable Pickens, Tooker, Culwell, Aronson, Even the abstract painter Pereira, the sculptor Noguchi, and the talented illustrator and caricaturist Saul Steinberg—whose drawings have a surprising energy in their own right—takes away from the force (of the exhibition), either because, as in the case of the first four or five, they ultimately tend towards academicism, or because, as in the case of Pereira and Noguchi, their feigned pose dilutes good intentions. And the incorporation of Steinberg – who is good, but with his limitations – seems almost a desperate last-minute gesture: because, even if he gave much more of himself, it would still be relatively insignificant from the point of view of modern art.

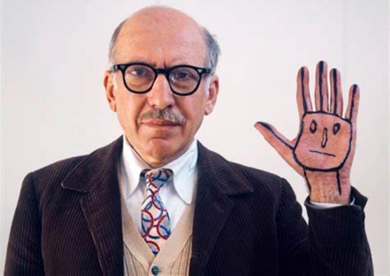

Steinberg avoided any typecasting: «I don’t quite belong to the world of art, nor to the world of cartoons, nor to the world of magazines, which is why the art world doesn’t really know where to place me.»

[…] Another artist also close to him was the painter, sculptor, engraver and ceramist Joan Miró (Barcelona 1893 – 1983 Palma), with whom he shared that world of childhood, as well as an inclination towards irony and the complexity of drawing.

[…] in his pictorial comments, a multitude of faces attentively contemplate a set of abstract paintings in an exhibition, and these same abstract forms blend with the hairstyles and other aspects of the viewers.

In his work, forms taken from Russian constructivism or references to Piet Mondrian are also evident, as in Luna Park (1968), where the Dutch neo-plasticist painter becomes an art deco fair attraction alongside Soren Kierkegaard and Arthur. Rimbaud.

…The text continues in the catalog, from this page 311 to page 324, which is where the text by María Teresa Muñoz begins.

The Saul Steinberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The girl in the bathtub. Page/12. May 13, 2011

By the writer, journalist, editor, translator and literary advisor Juan Forn (Buenos Aires 1959 – 2021 Mar de las Pampas), responsible for the wonderful back covers of the newspaper Pagina/12

A few days ago, a hundred-year-old Romanian woman named Hedda Sterne died in New York (she used her name Sterne and Hedda Lindenberk as sunomonyms). The obituary machinery was set in motion in the usual manner and the headlines were: “The last of the abstract expressionists dies.” They were referring to the gang of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and company, who during the first years of the Cold War, with the active collaboration of the CIA and the North American State Department, exported to the entire world the news that There was a new way of painting and that the capital par excellence of art was no longer Paris, but New York.

The abstract expressionists were all men, all egomaniacs, all pontificators and drinkers, and they burned like bonzes after fighting like mad dogs, after discovering to their stupor that they had triumphed. A double-page photo that appeared in Life magazine in 1951, with the title “The Irascibles,” had made them famous. In the photo taken by Nina Leen (Russia 1914 – 1995 New York), among all those goats, the little head of Hedda Sterne appeared, in the last row, the only woman. “I am better known for that photo than for eighty years of work. “If I had an ego, I would be depressed,” declared Sterne in the only report they made of him at the inauguration of his last exhibition, when he was 97 years old.

The photo called «Los Irascibles or Los Belicosos» brought together a group of important artists and was taken to protest the refusal of the Metropolitan Museum of New York to show the works of the Abstract Expressionists in the 1950s, in the largest retrospective of American painting to date. In that photo were Willem de Kooning, Paul Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Saul Steinberg, Hedda Sterne, among others.

The history of the photo and the group

In 1950, eighteen artists from what years later was called the New York School staged a protest against the exhibition “American Painting Today: 1950” that the Metropolitan Museum of Art was organizing for that year.

Many contemporary artists did not consider themselves represented in this exhibition that sought to bring together the best of American contemporary art and decided to organize a collective protest.

Among those artists were none other than the painters Jackson Pollock, Christopher Rothko, Barnett Newmann and Willem de Kooning.

In 2020, seventy years later, the March Foundation remembers that episode with an exhibition at its headquarters in Madrid, showing the works of the eighteen artists who participated in that protest, which began around the Studio 35 academy, in the Village of Nueva York, a space that the painters Motherwell, Baziotes and Rothko had launched in 1948 together with the sculptor David Hare.

Dissatisfied with the jury that the Metropolitan Museum had appointed to choose the representatives of contemporary North American painting, in their opinion of conservative tendency and little related to the avant-garde art that was being done in 1950, they wrote a letter to the president of the museum, Roland L. Redmond, signed by twenty-three artists.

The New York Times published that letter on its front page on May 22, 1950 under the headline «18 Painters Boycott the Metropolitan: They Accuse the Museum of Maintaining a Hostile Attitude toward Advanced Art.»

The Herald Tribune tried to disavow the protest of those artists in a harsh editorial that it published the next day in which it described the signatories as «The irascible 18.»

Despite everything, the Metropolitan held that exhibition at the end of 1950. Life magazine then proposed to the signatories of the letter that started the controversy that they pose for a photograph that is now historic. Fifteen of them attended and the image became an iconic symbol not only of the protest but of the ideology of what these artists thought about the future of American art.

La foto es ya el retrato canónico de la generación de artistas conocida como Escuela de Nueva York. Life publicó la fotografía el 15 de enero de 1951 ilustrando un artículo que titulaba “Una facción irascible de artistas avanzados ha liderado la lucha contra una exposición”.

The Hedda Sterne archives are deposited at the Smithsonian Institution. Included in the Archives of American Art, Hedda Sterne papers, AAA sterhedd 1939/1977. There is correspondence between Hedda and Saul Steinberg that contains little-known drawings by Steinberg that he sent to Hedda in a private and erotic nature.

His appearance in that photo was a misunderstanding. The bellicose men became enraged en masse with her and with Life, because the presence of a woman took away all seriousness from the matter (Hedda appeared in the photo with a little hat and a flirty purse hanging from her arm). Until the day before, they condescendingly told him, “You look like a man. “You could be one of us.” From that day on they decreed that she was neither abstract nor expressionist, something that she herself confirmed with a phrase that they did not find very funny: “It’s true, Mondrian is abstract. And, for an expressionist, there is no one better than my Saul.” Their Saul was Saul Steinberg, who for those painters was, yes, a brilliant cartoonist, even a gifted one, but a mere New Yorker cartoonist.

Steinberg was Romanian like Hedda, born in Bucharest and raised in the same environment, but they only met in New York. Hedda came from Paris, from where she had fled with the clothes on her back before being deported as a Jew, and Steinberg came from Milan, where she had been studying architecture before the anti-Semitic purges began: ‘I was four years older than him, and at nineteen I wasn’t running around with fifteen-year-olds,’ she said. Steinberg went to his small flat on 71st Street at noon in 1943 and stayed there for 18 years. In the bathtub of the flat, in 1949, he painted his famous portrait of Hedda, Girl in the Bathtub.

Unlike the Life painting, Hedda did not mind at all being Steinberg’s Girl in the Bathtub, even though they separated in 1961; she continued to live in the same small flat until her death, long after the bathtub painting had faded. Nor did she ever remove from the kitchen wall the beautiful diploma Steinberg had made for her, consecrating her as head chef of the house and of the city (though after Steinberg she never cooked for him again). When Peggy Guggenheim criticised Hedda for abandoning the kitchen and stubbornly refusing to label her paintings, Hedda corrected her: «I think it’s the style of the ego».

Since her arrival in America, she had been fascinated by the concrete and the immediate: «‘America is a country of the mind».

Sterne began painting moving cars, gigantic vegetables seen from the inside, totem-like aeroplane parts, still lifes with toilets (one of his obsessions: the differences between European and New World toilets), but to his astonishment and Steinberg’s hilarity, everything he did was abstract in the eyes of his colleagues: » ‘You could be one of us, You paint like a man».

Sterne unabashedly confessed that her dry spells had been plentiful, simply because she had lived for eighteen years with a man who never worked more than three-quarters of an hour at a time and who blindly relied on only one thing in the world: his formidable first stroke (according to Steinberg, ‘that stroke was his way of thinking’). During these crises of confidence, Hedda made freehand psycho-portraits of her colleagues and friends to distract herself: they were not physiognomic; they were exclusively of the psyche, in her opinion. She accumulated them over the years, and when she exhibited them, believing them to be the most abstract thing she had ever been able to do in her life, she was accused of having betrayed abstraction and (in 1971!) defenestrated once again. Steinberg had once drawn a story that Hedda told her, they had it hanging in the kitchen:

…a little girl is drawing. The mother asks her what she is drawing. How can you draw him if you don’t know what he looks like, says the mother. That’s why I draw him, the girl answers. Rothko and Barnett Newman were drinking one night in that kitchen. Barnett pointed to Rothko’s drawing. ‘That’s what we’re all forgetting,’ he said.

In 1943, she participated in The Exhibition by 31 Women held at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century gallery in New York.

Despite her work, Sterne has been almost completely ignored by the Art History of the post-war American art scene. Sterne saw his widely varying works as a flowing

From the moment she began to lose her sight until she went blind, Sterne kept a sort of logbook in the form of daily drawings, done in white crayon on white paper. She had set up her work table against the largest window of her flat and there she sat each day, crayon in hand, searching for the light with her milky eyes. In an interview filmed before her death, she is sitting at the same table, the light shining in from the side and illuminating her eyes, her hair is white and she has that serenity in her face that only the blind can have: she is literally glowing. ‘The doctors say you can’t wear out your eyes. It’s other things that wear them out, not use,’ he says at one point. ‘Ego is the tool some people use to make talent look like genius,’ she says at another point.

One sees her speak, recount her life, and sees all the women she was appear, all of them at once: the ten and the twenty and the thirty and the forty and the fifty, the fatal young woman Hans Arp and Duchamp fell in love with, the one persecuted as a Jew, the one rescued by New York, the one always attentive to the sensuality of the world, the artist immune to ego, the loner, the wise old woman. As if somehow, in that container, they were all preserved, preserved what most lose of themselves along the way. The novelist Henry de Montherlant (Paris 1895 – 1972 Ibid) said that there was only one way to portray happiness: with white ink on white paper.

Hedda Sterne

Eames and Saul Steinberg. C. 1950. 12,7 x 10,2 cm

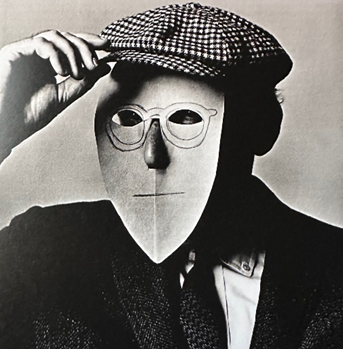

Part of a series in which a drawing by Saul Steinberg of a woman was projected onto Hedda Sterne, the projection aligns so closely with Sterne’s features that it becomes a kind of mask.

It anticipates the paper bag masks that Steinberg would begin to make several years later. Between 1959 and 1962, he animated many simple paper bags with faces drawn in crayon, ink or pencil, which he and his friends donned for the masked portraits taken by the photographer Inge Morath (Graz 1923 – 2002 Manhattan). The Eameses shared the Steinbergs’ interest in masks.

Charles, Ray Eames and Saul Steinberg

Shortly after Charles and Ray Eames developed the Shell Chairs (1948) with a fibreglass seat shell (mass-produced, a new seating typology) (4), Saul Steinberg visited the Eames Office in Los Angeles in 1950. Steinberg was already known for his humorous and sometimes provocative drawings of people and animals – especially cats – with which he repeatedly pushed the boundaries of traditional graphic media. During his visit, he spontaneously drew a series of lively caricatures on the furniture prototypes, floors and walls of the studio. He was particularly drawn to the Shell Chairs, and with a paintbrush he began to paint lines that flowed from one chair to the next, creating a small, imaginative cosmos of characters and animals, and the Eameses enthusiastically documented the spectacle in a series of photographs.

Nota

1

Alicia Chillida (San Sebastián, 1958) demonstrates an interest in the convergence of art, architecture, landscape and environmental issues.

Her most recent projects are the exhibitions Archivo Portera at the Museo de Arte Abstracto de Cuenca and Saul Steinberg, artist at the Juan March Foundation, Madrid.

-Moderator of the session ‘Artistic creation’ in the summer course Luis Martín-Santos and his time. Politics, society and culture in years of silence at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), San Sebastian.

-Invited by the Department of Systems Design Engineering, Keio University, Tokyo;

-Direction and production of the Edge’92 Biennial, Madrid.

-Coordination of the workshop Urban Interventions, directed by Muntadas for Arteleku, Donostia-San Sebastián.

-Directorship and production of Ulrich Rückriem’s permanent sculpture project: Siglo XX, XXI, in the Pre-Pyrenees of Huesca.

-Invited by the XII Havana Biennial.

-Director del Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

2

El cadáver exquisito era un juego surrealista de creación colectiva, que podía ser escrito o gráfico. En él, cada miembro del grupo realizaba su parte de la obra sin ser plenamente consciente de las demás. En este tipo de collage, el accidente desempeñaba un papel muy importante.

3

THE AMERICANS. Frank Robert- Kerouac Jack. ISBN 978- 84-18934-03-2. Editorial la Fábrica. 180 pp.

A masterpiece in the history of photography, this book shows an exciting portrait of America in the 1950s as a road movie.

Los Americanos was conceived during 1955 and 1956. First published in 1958, it did not take long to become a landmark, the most influential photography book in the world and a touchstone of American identity.

Robert Frank, who travelled the roads of 48 American states taking photographs of ordinary people (a parade in New Jersey, a funeral in South Carolina, shop windows in Washington, a cocktail party in New York, roads in Idaho, a picnic in California, Tennessee, Utah…) thanks to a grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, conceived this project as a result of his relationship with the beat generation, after meeting personalities such as Bill Brandt, Walter Evans and the poet Allen Ginsberg.

4

Vitra currently uses recycled post-consumer plastic to manufacture the shells of the Eames Plastic Chairs and fibreglass-reinforced polyester resin for the Eames Fiberglass Chairs.

They are produced in more than 170,000 configurations, 23 shell colours and 36 upholstery options. The seat shells, whether fibreglass, recycled plastic or welded steel wire, conform to the contours of the human body for a higher level of comfort.

Continued on https://onlybook.es/bl

—————–

Our blog has been read more than 1,300,000 times.

Nuestro Blog ha superado el millón de lecturas

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico.blogspot.com

Salvemos al Parador Ariston de su ruina

Let’s save the Parador Ariston from its ruin

http://onlybook.es/blog/el-parador-ariston-una-ruina-moderna-por-hugo-a-kliczkowski/