The Women Book

T.C. Boyle (1)

Translated by Julia Osuna Aguilar

Impedimenta Publishing. October 2013

978-84-15578-89-5

Although, as Boyle indicates in his book, the text is a fictional recreation, the fictional situations and dialogues are from real people.

The book deals with the relationship between Frank Lloyd Wright and his three wives and his partner.

- Caherine «Kitty» Tobin Wright (1871–1959), married to Wright from 1890–1922.

- Her partner, referred to in many texts as «Wright’s lover,» Mamah Borthwick Cheney (1869–1914), was with Wright from 1909 until his violent death in 1914.

- Maude Miriam Hicks–Noel Wright (1869–1930), married to Wright from 1914. They married in 1923 and divorced in 1927.

- Olga Ivanovna – Olgivanna- Lazovich Milanoff Hinzenberg Lloyd Wright (1897 – 1985), married from 1928 until Wright’s death in 1959. In 1926 they had their only daughter, Iovanna who, like her mother, studied dance and movement in Paris with the mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff.

Caherine Tobin

Frank and Kitty married in 1889.

Kitty gave birth to their first son, Lloyd, in 1890, John in 1892, Catherine in 1894, David in 1895, Frances in 1898, and their youngest son, Llewellyn, in 1903.

Wright’s Statement to the Press

The Dodgeville Chronicle newspaper reported in its January 5, 1912, article that Wright told them:

“The only circumstance which serves as a basis for asserting that I eloped with another man’s wife, abandoned a wife, or deserted my children, is found in the fact that I neglected to inform the Chicago newspapers of my intentions and the arrangements that had been honestly made with all who had a right to be consulted.”

Maude Miriam Noel

In December 2014, Wright received a first letter of condolence from Miriam.

According to biographer Finis Farr (1904–1982), “In a second letter, Noel suggested they meet: A few days later, Miriam Noel sat across Wright’s desk… She saw a woman who was no ordinary person, and who retained much of what had evidently been great youthful beauty. Opulently dressed in a sealskin cloak, her pale complexion contrasted with her abundant dark red hair…

“How do you like me?” Miriam Noel asked.

“I’ve never seen anyone who looks remotely like you,” Wright said.

In his autobiography, he would write, “Marriage to Miriam was the ruin of both of us.”

Edgar Tafel (1912–2011) contacted the Taliesin Community Foundation in Wisconsin by mail and was informed that the tuition fee was $675. Since he could only muster $450, the equivalent of his own tuition at NYU, he wrote to Wright, who accepted the partial payment.

Other sources confirm that, in September 1932, the tuition fee was indeed $675. (Architectural Records and Papers of Edgar Tafel 1919–2005. Documenting the life and career of Tafel, who had been a Taliesin Fellow since 1932.) (2)

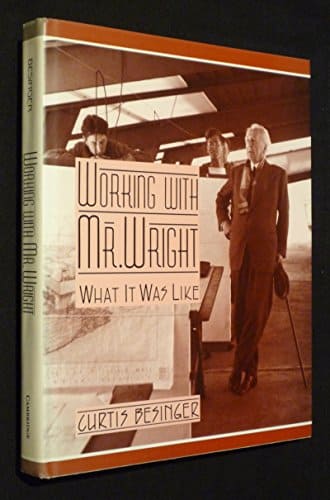

Working with Mr. Wright: What It Was Like. Book.

Curtis Besinger. ISBN 9780521481229

Publisher: Cambridge University Press, 1995. Text in English

In 1931, Wright and his third wife, Olgivana, created the Taliesin Fellowship, a community of apprentices who, along with their families, lived, worked, and studied with Wright, first at Taliesin East in Wisconsin and then at Taliesin West in Arizona.

But the workshop needed to be promoted, so he put out a call to prominent scholars, artists, and friends, announcing his plan to establish a School at Taliesin Spring Green, to implement a teaching method for Architecture based on the concept of “Learning by Doing.” Full text at https://onlybook.es/blog/las-obras-de-frank-lloyd-wright-parte-6/

Tafel wrote the 1979 book “Apprentice Genius: Years with Frank Lloyd Wright” and the 1993 book “About Wright: A Scrapbook of Memories by Those Who Knew Frank Lloyd Wright.”

In 1995 he produced “The Frank Lloyd Wright Way” a film that won first prize at the 1995 Houston International Film Festival.

In 2012, “A Taliesin Journal: A Year with Frank Lloyd Wright” was published, featuring his journal entries. It chronicles the experiences of Priscilla and David Henken as a married couple from 1942 to 1943.

«IN THE CAUSE OF ARCHITECTURE.» The Taliesin Fellowship

By John W. Geiger, Wright Apprentice

When I went to meet with Wright, there was a tacit agreement to pay $1,500 ($24,000 in 2025 terms) for one year for room and board, the privilege of working 40 hours a week on Wright’s behalf, and to attend Saturday nights and Sunday mornings and evenings regularly in exchange for his consent to teach me “absolutely nothing”—this was an apprenticeship, not a school.

For Wright, the Fellowship was an opportunity to work with a group of enthusiastic men and women and a source of income (26 x 500 = $13,000 per year in 1932 terms, equivalent to $303,000 in 2025 terms). Geiger.

Other apprentices included David George, Dick, and Mary Lim.

«In the cause of architecture,» Wright said, «it was impossible to teach someone to be creative in architecture.»

Geiger recalls that a quote from Walt Whitman’s (1819–1892) Song of the Open Road was written on the wall of the Hillside Theatre in 1932.

Here is the test of wisdom (creativity);

Wisdom is not finally tested in schools;

Wisdom cannot be passed from one who has it to another who does not;

Wisdom is of the Soul; it is not susceptible to testing; it is its own test.

The use of the word “student” implies a Master, but by the time the Fellowship was formed a year later, the idea of a Master had been abandoned forever. There were no Masters in the Fellowship, and no one was taught anything. If we learned anything at all, it came through the process of absorption by being immersed in Wright’s environment.

From various sources, one can glean a list of advice Wright gave to young architects; some are excerpts from “Modern Architecture,” 1931, published in Writing and Buildings, Meridian Books, NY. (3)

«Frank Lloyd Wright Writings & Buildings» Paperback – January 1, 1960. Publisher Meridian Books, authors Edgar Kaufmann & Ben Reaburn. ISBN 978-0529020574

-He considers building a chicken coop as important as a cathedral. The size of the project matters little in art, beyond the economic aspect. What really counts is the quality of character. Character can be great in the small and small in the large.

-Don’t take anything beautiful or ugly for granted; on the contrary, dismantle every building and question every detail. Learn to distinguish the curious from the beautiful.

- Acquire the habit of analysis; over time, analysis will allow syntheses to become a habit of mind.

- Thinking in simple terms, as my former teacher Louis H. Sullivan used to say, means reducing the whole to its parts in simple terms, returning to basic principles. Do this to move from the general to the specific and never confuse them or be confused by them.

- Sullivan is seen through Wright. Full text https://onlybook.es/blog/la-escuela-de-chicago-3-arq-louis-h-sullivan-su-vida/

- Go where you can see the machines and methods in operation that construct modern buildings…observe direct and simple construction until you can work naturally into building design from the nature of construction.

- Take your time to prepare. Ten years of preparation for the preliminaries of architectural practice is not enough for any architect who wishes to excel in the… architectural practice.

- Immediately begin to form the habit of thinking, thinking “Why?” about any effect you like or dislike.

- Do not enter any architectural competition under any circumstances, except as a beginner. No competition has contributed anything valuable to the world in architecture. The jury is a chosen average. The first thing the jury does is review all the designs and discard the best and worst to, as an average, arrive at an average over an average. The net result of any competition is an average among the averages.

In 1932, Wright published «Advice to the Young Architect, of obvious connotation.»

Originally a square, triptych publication printed in black and red inks, it was later reprinted in a new format to be placed as an insert in the Journal of the Taliesin Fellows (Issue 4, Summer 1991). Research was done by Dennis Stevens, and design by JTP art director Louis Wiehle.

About Wright

The Taliesin Fellowship was an unconventional organization. Frank Lloyd Wright was a complicated man and “no angel,” but he did have a vulnerable side that he protected with great bravado. Apprentice Bob Bishop comments: in a letter to his fiancée, a conversation he had with Wright in 1934, “…We discussed at length his inability to have close friends, and he “confessed” that his worst weakness, and the one that most troubled his conscience, was his lack of concern for others as persons in their own right.” own, to be appreciated, remembered, and befriended…» Edgar Tafel, «About Wright», John Wiley & Sons, Inc., page 109).

The Fellowship’s social structure was organized by Mrs. Wright according to a model established by Gurdjieff at his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in France.

Olgivanna studied for several years in Russia with the Greek-Armenian mystic and philosopher Georgi Gurdjieff (1866–1949). In 1917, at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution, Olgivanna fled Russia with Gurdjieff and his followers, and that year her daughter Svetlana was born. Read the full text at https://onlybook.es/blog/las-obras-de-frank-lloyd-wright-parte-8-su-vida/

Wright had no interest in the day-to-day affairs of administration, but in the event of a dispute, he made the final decision.

Mrs. Wright’s followers were known as «the little kitchen crowd.» as John DeKoven Hill puts it in his book (pp. 477, The Regents of the University of California, 1977).

Wright had his loyal secretary, Gene Masselink, construction manager and structural engineer Wes Peters, and Jack Howe, who ran the newsroom.

Ms. Wright‘s primary assistants were Kay Schneider and Davison Rattenbury, who, among their other responsibilities, scheduled the food preparation tasks. Breakfast and work were from 5:30 a.m. until after dinner, which concluded around 7:30 p.m.

Music

The photo shows Curtis Besinger (who joined the Fellowship in 1939 and remained in the choir until 1955) sitting at the piano during choir rehearsal. The photo was taken in 1940 or 1942 in a room at Taliesin West known as the Kiva.

Front row from left to right: Besinger at the piano, Wes Peters, Davy Davison, Aaron Green, and Cary Caraway. Standing behind Wes are Gene Masselink and John Hill. Behind Wes are Jack Howe, Lock Crane, and Marcus Weston. Behind Gordon Lee are Jim Charlton, Norman Hill, Gordon Chadwick, Chi Ngia Show, Bob Mosher, and Kenn Lockhart.

He discusses the experiences of another apprentice, John Geiger, at both Taliesin East in Wisconsin and Taliesin West in Arizona. “I joined the choir early on. We practiced for an hour every morning after breakfast. A few years later I joined the musical ensemble. I practiced an hour a day after lunch. Where else could you spend two hours a day making music and another six hours a day pouring concrete, doing carpentry, and maybe even working in the drafting room or kitchen, as part of your everyday life? It was a productive and fulfilling lifestyle.”

I remember one of Wright’s “sermons” that he used to give on Sundays after breakfast. He was talking about developing a muscular body and then he said, “…and through the exercise of the spirit you will develop spiritual muscle.” Edgar Kaufmann Jr. donated a tape recorder and Bruce Pfeiffer has been recording his talks ever since.

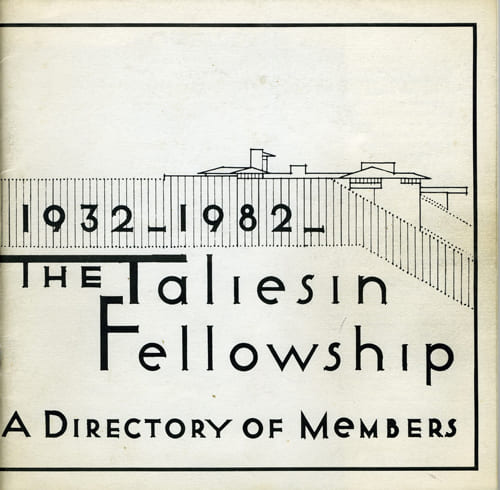

Shortly after a visit to Taliesin by Elizabeth (Bauer) Mock (Kassler) in March 1979, she decided to compile a retrospective directory of the Taliesin Fellowship for its 50th anniversary. This monumental task was undertaken before the age of computers and had to be done entirely by hand. The directory, 1932-1982, The Taliesin Fellowship, A Membership Directory, was published in the fall of 1981 with a printing of 450 copies. Geiger has copy number 441; she made it possible to reference the biographical data she compiled.

From April 1928 to April 1959, arranged alphabetically by surname (625 entries).

1889–April 1959, arranged alphabetically by surname (182 entries).

Grouped by year of first association and arranged alphabetically within each group (790 entries).

Elizabeth (Bauer) Mock (later Kassler) (1911–1998), a Taliesin Fellowship recipient after college, was one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s first apprentices, working from September 1932 to April 1933, where she met her first husband, Rudolph Mock.

She was an influential advocate of modern architecture in the United States and the first Taliesin-trained scholar to join MoMA, the Museum of Modern Art, where she served as chair of the Department of Architecture and Design and as a professor at the University of Oklahoma.

Mock worked in Wright’s studio from January 1931 to April 1933. She was one of four Taliesin apprentices arrested for assaulting C. R. Secrest, who had broken Wright’s nose over an employment dispute.

Elizabeth completed the first directory of the Taliesin Fellowship in 1981. The Taliesin Fellowship, A Directory of Members, and inspired the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation to develop similar directories.

Wright’s broken nose

Photograph of Wright with four of his students—Rudolph Mock, Karl Jansen, Sam Ratensky, and William Peters—on November 19, 1932.

The clipping reads: «Following a street fight in which C.R. Secrest of Madison is said to have broken the nose of world-famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright, four students from Wright’s school of trades and crafts at Taliesin, Wisconsin, drove to Madison, entered Secrest’s home, and beat him until the victim drove them off with a butcher knife. In court, the students pleaded guilty and are awaiting sentencing.»

According to Brendan Gill in «Many Masks 332,» the argument centered around C.R. Secrest’s wife, who had worked at Taliesin.

It was alleged that Wright owed him wages. During the argument, Secrest broke his nose. Wright’s four apprentices were fined for whipping Secrest, while Wright himself was eventually found guilty of withholding wages.

He was fined and subsequently left town.

In the chapter “Summer of 1948” he comments… one afternoon, during tea in the tea circle, Tal Davidson, son of members Kay and Davy, and Brandoch Peters, was playing and cavorting in the nearby Hill Garden…they knocked over a large jar of Ming tea that was standing on a stone; the jar rolled down the hill and broke into hundreds of pieces.

Was there a moment of silence and suspense…would Mr. Wright have been angry?

Instead, he seemed to accept this philosophically as one of the risks of living with works of art, and particularly with small children.”

Ling Po, a member of the Ming Dynasty Community, reattached the large teapot.

Notes

1

Thomas Coraghessan Boyle (Peekskill, New York, 1948) is an American novelist and short story writer. Since the mid-1970s, he has published sixteen novels and over 100 short stories. He won the PEN/Faulkner Award in 1988 for his third novel, The World’s End, in which he retraces three hundred years of New York State history.

He is currently a professor of literature at the University of Southern California. His works have been translated into more than a dozen languages, and his stories have appeared in the most prestigious English-language publications of the genre, including The New Yorker, Harper’s Bazaar, Esquire, The Atlantic Monthly, Playboy, The Paris Review, GQ, Antaeus, Granta, and McSweeney’s.

2

This collection is available for use by appointment in the Drawings and Archives Department of the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University. Information: avery-drawings@library.columbia.edu.

3

The Nomad Sketchbook. Thenomadscketchbook. Josh Nelson. 8/22/23

——————————————————

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico7.blogspot.com

Post navigation

Entrada anteriorEileen Gray, Le Corbusier y Badovici en Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. 1a parte. (mb)