Previous text read https://onlybook.es/blog/frank-lloyd-wright-some-key-stages-of-his-life-part-3-mbgb/

Frank Lloyd Wright and Automobiles

The Symbolism of the Road Trip

Thomas Boyle, in his book The Women, mentions Wright’s car, a Cord Phaeton, as the fastest and most majestic vehicle ever built.

If we were to visit the Auburn Cord Duesenberg Automobile Museum in Indiana, we would see Wright’s 1929 Cord L-29 Cabriolet, which he acquired in the 1950s, alongside more than 125 other classic cars.

He had it painted in a bright shade he called «Taliesin Orange,» after the Taliesin emblem in Spring Green.

It was known as «Cherokee Red.»

The Cord L-29 is powered by a Lycoming inline-eight engine with a displacement of 4893 cubic centimeters and 125 horsepower, and weighs 1,950 kilograms.

The Cord L-29 Cabriolet was the first production car with front-wheel drive and cost $3,295 ($60,800 today).

Its «modern» style and engineering feat attracted many buyers. This impressive convertible was acquired in the 1950s by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, its legal guardian until Wright’s death in 1959.

Wright’s interest in and attraction to automobiles is a subject of much study, to the point that he eventually owned numerous elegantly designed cars, including Bentleys, Jaguars, Packards, Cadillacs, and Mercedes-Benzes.

This interest has motivated Director Brandon J. Anderson of the Auburn Cord Duesenberg Automobile Museum, which opened more than half a century ago, to teach courses exploring the history of this fascination, both in his personal life and in his design concepts.

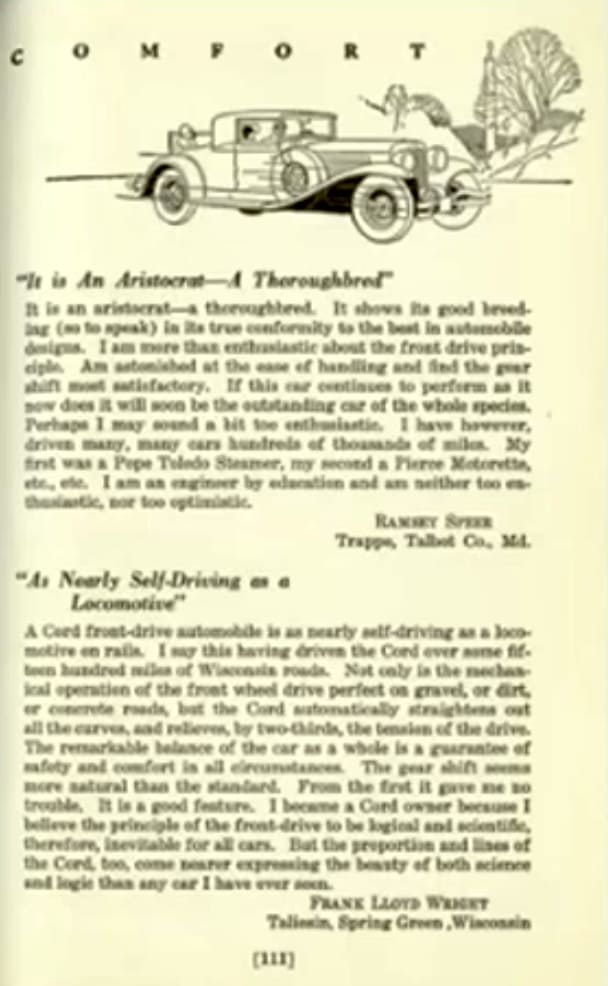

“A front-wheel-drive car is like a locomotive on rails. I know this because I’ve driven the Cord for over 500 miles on Wisconsin roads. Not only is the mechanical operation of the front-wheel drive perfect on gravel or dirt roads, but the Cord automatically straightens out of turns and reduces driving stress by two-thirds. The remarkable balance of the car as a whole is guaranteed and maintained under all circumstances.”

“The gearshift is so natural that one forgets it’s not standard. From the very beginning, it offered me such a combination of virtues that I became the owner of a Cord, because I believe the principle of front-wheel drive is logical and therefore inevitable for all cars. But the proportion and line of the Cord also seem to express the beauty of both science and logic better than any automobile I have ever known.” Frank Lloyd Wright

“He’s an aristocrat. A genuine thoroughbred. He carries himself with the dignity that only the best in his class possess. The elasticity of the front-wheel drive, and, in my opinion, the perfection of this car, make it the finest example of its kind.» Ramsey Spike, Engineer

This video is very interesting because of all the details explained by Brandon J. Anderson. «Frank Lloyd Wright and the Automobile.»

Color

Bright orange hue, known as «Taliesin Orange».

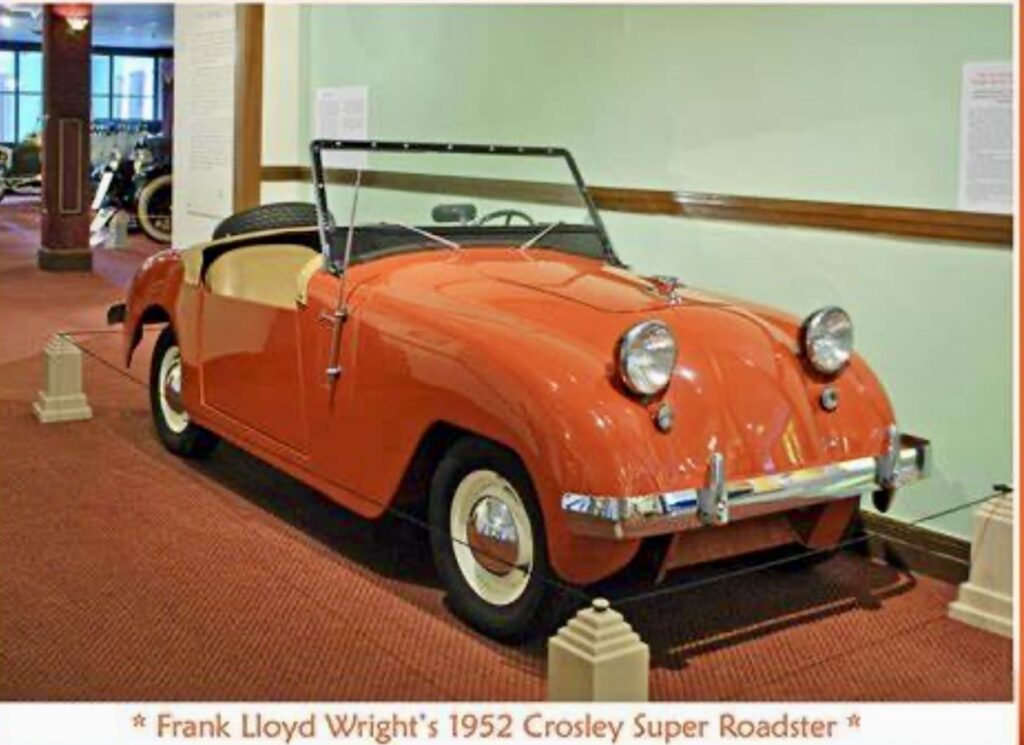

«Cherokee Red» can be seen on Wright’s 1952 Crosley, which is also in the museum. The finish on this Cord is quite similar. Wright had many of his cars painted in a bright shade he called «Taliesin Orange.»

The 1952 Crosley, part of the collection of the Cord Duesenberg Automobile Museum in Auburn, was originally owned by Wright and has been repainted in Cherokee Red during the restoration.

Crosley automobiles, manufactured in Indiana, were introduced in 1939.

By 1948, they had achieved success, with record sales and a wide range of body styles. However, by 1952, sales were only a third of those of 1948, and production had to be discontinued.

Frank Lloyd Wright and his wife Olgivanna in a 1949 Crosley Hotshot. Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York City), This was his second Cord Phaeton, the first one he bought new in 1929.

Color

Steve Sikora, writing on the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation blog on February 22, 2019, writes that there are many Cherokee reds.

The color Frank Lloyd Wright immortalized in his name evolved over time from a deep, earthy brown to a clay red with a dusty orange tinge. Cherokee Red first appears in a letter from Gene Masselink to Nancy Willey dated February 26, 1936.

What color is Cherokee Red?

Steve Sikora, creative director and owner of the Malcolm Willey House in Minneapolis, introduces the color Frank Lloyd Wright made famous: Cherokee Red! This stream was hosted live on June 8, 2021, as part of Wright Sites x PechaKucha Vol. 3, exploring the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright with 20×20 talks in honor of the famed architect’s 154th birthday.

Frank Lloyd Wright, his wife Olgivanna, and their daughters Svetlana and Iovanna in February 1929 in a Packard Deluxe Eight, en route to Wright’s temporary studio in the desert near Chandler, Arizona. Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

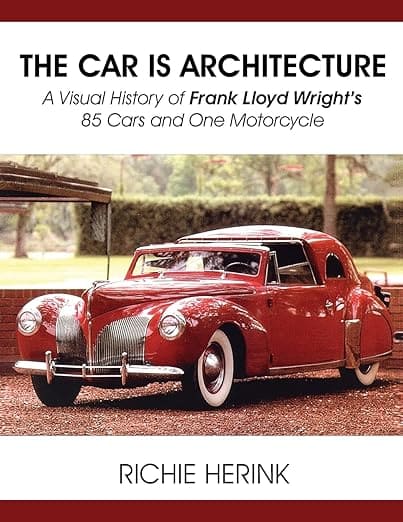

The Car Is Architecture – A Visual History of Frank Lloyd Wright’s 85 Cars and One Motorcycle.

Author Richie Herink.

English edition. Softcover. 112 pp. Illustrated, January 7, 2015

ISBN 09781604148435. 21.6 x 27.9 cm

Author Richie Herink wrote about Wright’s obsession with cars: «He saw them as becoming the greatest agent of social, economic, environmental, and personal change the world has ever known; the automobile is architecture.»

Was it 85 or 54 cars?

Cars were one of Wright’s great obsessions, along with architecture and Japanese prints… the book tells of Wright’s 85 cars and motorcycle in the order they were acquired between 1911 and 1959.

While he mentions all the cars used at Taliesin, it seems exaggerated to mention 85. Ed Winkel, director of the Arizona Concours held in January 2014 at the Arizona Biltmore Resort (2400 E Missouri Ave, Phoenix), has been able to track down 54 documented automobiles that belonged to Wright.

Automobiles

He owned a fleet of Mini cars, including Bantams and five 1949 Crosleys, for the staff and architects of both Taliesins.

He drove the finest cars in the world, including the Auburn, two Cord L-29s (Phaeton and Cabriolet), a Jaguar Mark IV, a Mercedes-Benz, a Cadillac, a 1934 Duesenberg, which some collectors say surpassed a Rolls-Royce in its era; two 1935 Fords, three 1936 Fords, a convertible sedan, and two station wagons.

A 1909 Stoddard Dayton 45 hp Model K Roadster, similar to the one that had won Indianapolis, was the year 1909 and was being designed by the Robie House.

Roadster Stoddard

Also featured are a 1937 AC 16/80 sports car, a Packard, the famous 1940 Lincoln Continental V12 Cabriolet, and a 1953 Bentley R-Type Sedan Coupé convertible.

The cars, both the AC 16/80s and the “Hot Shot” pickups, served as both design teaching aids and transportation, with apprentices using them on trips across the country during the 1950s.

“America had become a nation with a car culture almost overnight and a country where people were always on the move, traveling somewhere by car.”

Wright, too, loved moving, especially moving. A news story in an April 1940 issue of Architects’ Journal, headlined “Open-Top Cars,” described the annual pilgrimage as organized with “Hollywood exuberance.”

An excerpt from a letter described the scene as «a safari consisting of five or six truckloads of young people, pots and pans, grand pianos, and cement mixers.»

Wright started in the back of the caravan in a sleek new red Lincoln Zephyr Cherokee. «Since he never drives less than 60 miles per hour, he leaves a few days later than everyone else and, of course, arrives early.»

In the 1920s, he endured a series of failures, health problems, and experimental plans before recalibrating his strategy to regain his place as the country’s foremost architect in the late 1930s. Arizona represented both renewal and rebirth.

At first, however, the desert reflected moments of despair; his first trip to Arizona occurred during one of the worst periods of his career. In 1927, after completing a series of commissions in California, he desperately needed to find work, and as a resource, he began touring the Midwest giving lectures.

The lack of work and income at the time nearly meant losing the place he held most dear: Taliesin, the home, studio, and complex he had designed and rebuilt over the past few decades, was virtually at the mercy of creditors (the Bank of Wisconsin foreclosed on the property and was about to auction it off). Wright was rescued by the generosity of his patron and friend, Darwin Martin, a New York businessman who devised a plan to raise funds for Frank Lloyd Wright Incorporated by selling shares in his future projects to investors. It is unclear whether they ever received any dividends from their investments.

Darwin Martin was one of the directors of the Larkin firm who did the most to help Wright design the company’s administrative building; over the years, the two became friends.

Read the full note in https://onlybook.es/blog/gb-wright-larkin-darwin-martin-complex-midway-gardens-2nd-part/

When a former student, Albert McArthur, invited Wright to advise him on the design of the Arizona Biltmore Hotel in early 1928, he couldn’t refuse. The agreement revealed the difficult situation the proud architect found himself in: he would receive compensation for his expertise, but would not be recognized for the final design, something difficult for Wright’s personality.

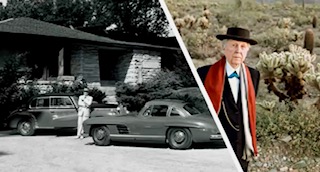

It was time to move on. Traveling, Wright delighted in his passions—architecture, automobiles, and the American landscape. Many decisions were influenced and influenced by the fact that Olgivanna met a doctor who told her that «if she took her husband to the desert every summer, it would extend his life by 20 years.» This also influenced many decisions.

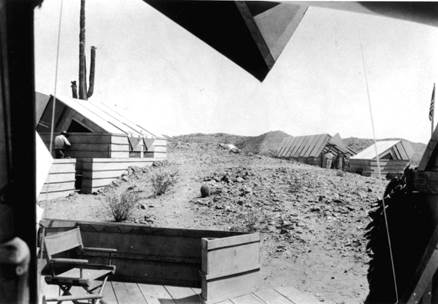

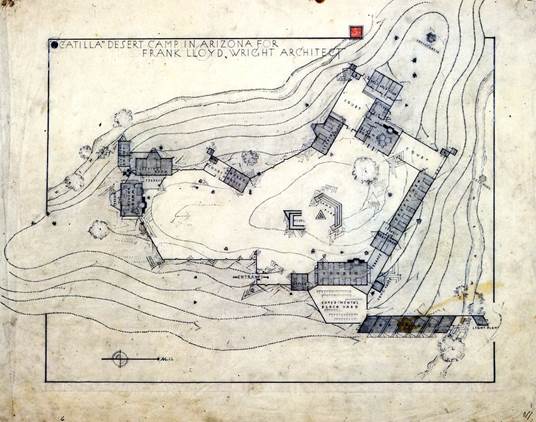

During that first stay in 1928, Wright met a local real estate developer, Dr. Alexander John Chandler, who convinced him to work on the San Marcos Hotel in the desert in Ahwatukee, Arizona. Wright seized the opportunity and built a small tent village called Ocatilla so his team could design a wide range of new buildings for his client. Wright had hoped to earn $40,000, but after the crash hit, he ended up $19,000 in debt. His only real reward was publicity, as photographs of his desert camp appeared in several international magazines.

Ocatilla

Wright named the camp Ocatilla, modifying a letter of the name Ocotillo, a plant that grew abundantly in the area.

Wright and his apprentices built it from 1927 onwards, it would be a base camp where the progress of the San Marcos Hotel could be observed.

In his autobiography, he writes, “And soon you will see them as a group of giant butterflies with scarlet spots on their wings, gracefully adapting to the crown of jagged black rock outcrops that rise gently from the desert floor.”

Wright personally designed the tent-inspired complex, which was built very quickly.

Despite his financial difficulties, he returned to Wisconsin in style, purchasing a luxurious Packard Phaeton convertible with a fee from a New York client.

The aborted Hotel San Marcos in 1929 led to the abandonment of Camp Ocatilla, which eventually disappeared, as the materials were diverted to other uses.

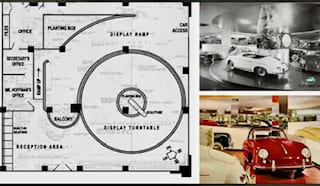

Hoffman Auto Showroom

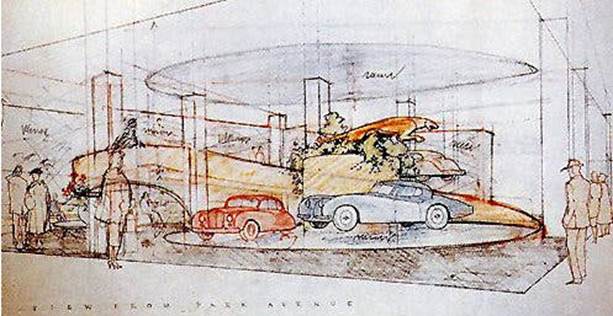

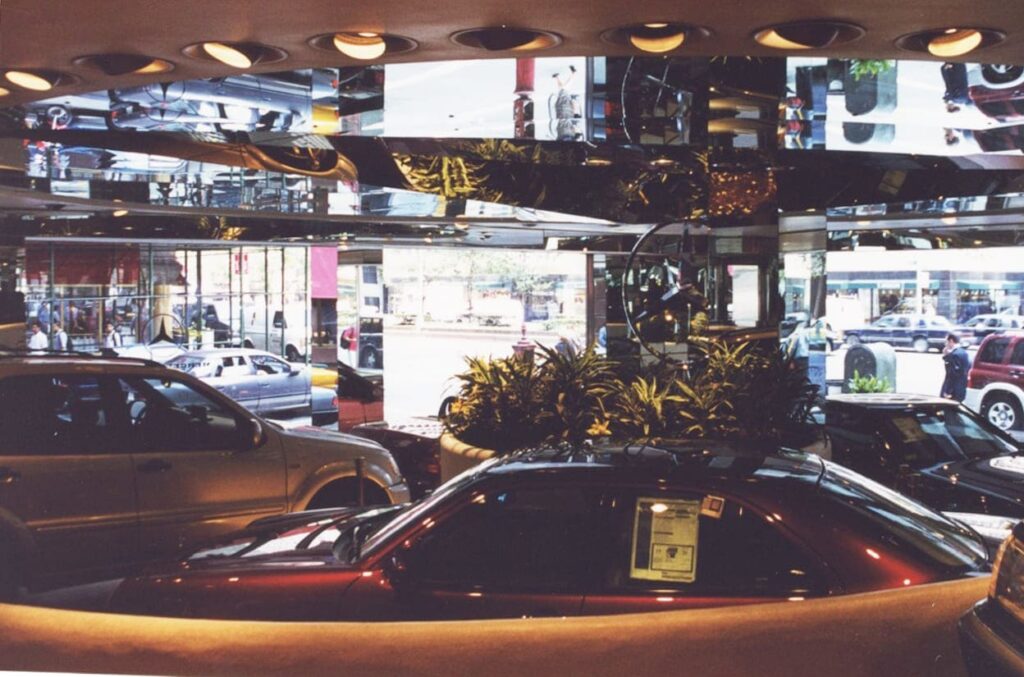

In 1954, Maximilian Edwin Hoffman (1904–1981) commissioned Wright to design the “Hoffman Auto Showroom” for his Jaguar automobile dealership at 430 Park Avenue and 56th Street in New York City.

The space, a spiral ramp, was designed for Austrian-born automobile importer Maximilian (Max) Hoffman, who emigrated to New York during World War II and founded his importing company in 1947.

The product was a commission between two friends, one an automobile importer and the other a highly regarded architect in the United States. They both shared a love of designer automobiles and their display.

He was already in discussions with Hoffman about the design of his home in Rye, New York, when discussions about the showroom began.

Douglas Steiner, who has written extensively about the architect (4), has commented that part of Wright’s fee for the design of the showroom was paid with two Mercedes-Benz vehicles, which made the association even more interesting to Wright.

Agreeing immediately, he wrote to Hoffman that his Porsche ownership would be «good for the appreciation of this fine foreign automobile,» as there were none «within hundreds of miles of Madison, Wisconsin.» (5)

In 1955, the new Porsches were displayed on the spiral ramp of the Wright-designed Park Avenue showroom. Credit: Ezra

A rotating platform held three or four cars; a ramp behind it accommodated one or two more. This spiral anticipated the design of the Guggenheim Museum, opened in 1959.

Luxury European models were displayed there, including Jaguars, Delahayes, Austins, Porsches, Mercedes-Benz, and even Volkswagens.

In 1958, Mercedes-Benz purchased Hoffman and remained in the Park Avenue space until moving to a larger showroom in a new dealership on 11th Street.

Year 2012

Janet Halstead, executive director of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, a Chicago-based group dedicated to preserving Wright’s work, said that «after learning of the planned demolition from one of its members, her organization attempted to have the city designate the exhibition hall as a historic landmark.»

«We have a network of members and professionals who informally monitor Wright buildings in their regions and in the media, and we often learn about situations through these ‘Wright Watch’ participants,» she said. «They constitute a kind of early warning system for risks to Wright buildings. We submitted a formal request for an assessment to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in August 2012.»

Year 2013

On March 22, Matt Chaban of Crain’s New York Business reported on the possibility of the building being destroyed.

On March 25, a letter was sent informing the building’s owner that a landmark designation was being discussed.

On March 28, the owner applied to the city’s Department of Buildings, an independent agency, for a demolition permit, which was granted. Demolition took place the following week to make way for a TD Bank branch.

Calls and emails to the owners, Midwood Investment and Management and Oestreicher Properties, and to the building’s managers were not returned.

Frank Lloyd Wright in New York: The Plaza Years 1954–1959 Hardcover – September 5, 2007. Gibbs Smith Publishers. Authors: Debra Pickrel and Jane King Hession, with a preface by Mike Wallace. (6)

Preservationist Debra Pickrel wrote about the showroom’s destruction in Metropolis magazine. (7)

The Hoffman Auto Showroom on Park Avenue is lost. May 9, 2013.

“It wasn’t a masterpiece, but it was the work of the master. Every day, hundreds of people passed by the gleaming space, but few realized its significance. A gem hidden in plain sight, the Hoffman Auto Showroom at 430 Park Avenue opened in 1955. It was one of three Frank Lloyd Wright projects in New York City. And now, it’s gone.”

La sala de exposición también fue una joya para mí. Es un personaje de mi libro, Frank Lloyd Wright in New York: The Plaza Years, 1954-1959.

The Ramp

The exhibition hall’s signature ramp was also one of Wright’s several design experiments with the spiral, the extraordinary culmination of which was the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Debra Pickrel writes, “I spent a lot of time studying, visiting, and writing about it. Imagine my surprise on a warm day last month when I walked by the exhibition hall and witnessed it being gutted. A woman in construction gear, standing in front of the open door, beckoned pedestrians past clouds of dust and containers filled with the exhibition hall’s remains on their way to a nearby garbage truck.”

“When longtime tenant Mercedes Benz vacated the space last December, the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, among others, had been actively advocating to save it. But the fate of historic New York interiors…is always precarious.”

“The Landmarks Commission was unaware the site had been demolished until we received a witness report stating the space had been completely gutted,” Ms. Halstead said.

The conservancy’s president, Larry Woodin, issued a statement: “It is very disappointing that the City of New York was unable to act quickly enough to prevent the demolition of this Wright space.”

“This costume jewelry store,” as he described it in an October 13, 1955, letter to Max Hoffman, was the architect’s first permanent work in the city, his first built automobile design, and one of his few interior-only projects. Executed during New York’s post-World War II commercial construction boom, it was the architect’s only gesture along the corporate corridor of International Style buildings designed by his rivals, the “glass box boys,” as journalist and film critic Brendan Gill (1914–1997) wrote in Many Masks, A Life of Frank Lloyd Wright (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1987).

“Host to an array of the latest and greatest imported cars for nearly 60 years, the Hoffman Auto Showroom was a small but important piece of our built history, sadly underappreciated in a place where the value of square footage frequently exceeds its contents.”

The Max Hoffman House

In 1955, Wright designed a large house and garden for the Hoffmans on the shore of North Manuring Island overlooking Long Island Sound.

It was located on the waterfront in Rye, New York, in Westchester County.

Built with stone, plaster, and slate roofs, it has a copper-clad cornice under the roof edge.

The L-shaped house is a single-story, 5,600 square foot house on a 80,000 square foot waterfront lot overlooking Long Island Sound.

The residence has five bedrooms, six bathrooms, guest quarters, and a climate-controlled garage.

It features a Japanese garden designed by Stephen Morrell, curator of the John P. Humes Japanese Garden in Locus, New York.

History of the Hoffmann House

Emily Fisher Landau (1920–2023) purchased the house in 1972 and lived there until 1993. She was a director of the Fisher Brothers real estate firm. Due to her donations to the Whitney Museum of American Art, the fourth floor bears her name. She was a member of the Painting and Sculpture Committee of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Board of Trustees of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe.

In 1972, Taliesin Associated Architects, a firm founded by Wright’s disciples after his death, built an additional wing to the north.

Between 1993 and 2019, it was occupied by Tom and Alice Tisch (son and daughter-in-law of former CBS chairman and CEO Laurence Tisch). An interior renovation designed by architect Emanuela Frattini Magnusson took place in 1995.

In April 2019, it was purchased by fashion designer Marc Jacobs, who lives there with his partner Charly Defrancesco.

Notas

4

In this link http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Artifact%20Pages/PhRtS389Aug01.htm

Exterior photographs taken by Douglas Steiner in August 2001 are shown. They are of William B. and Elizabeth Tracy’s home in Normandy Park, Washington, in 1955.

5

Frank Lloyd Wright, letter to Max Hoffman, July 14, 1952, Frank Lloyd Wright Archives.

6

Frank Lloyd Wright in New York: The Plaza Years, 1954–1959 examines the momentous five-year period in which one of the world’s greatest architects and one of the world’s greatest cities dynamically coexisted. Authors Jane Hession and Debra Pickrel bring each of these peerless characters to life, exploring the fascinating contradiction between Wright’s oft-expressed disdain for New York and his pride and pleasure in living in one of the city’s great landmarks: the Plaza Hotel. From his suite, or “Taliesin the Third,” as it came to be known, Wright oversaw the construction of the Guggenheim, spoke to the New York press, and hosted many famous visitors such as Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller.

7

Debra Pickrel, principal of Pickrel Communications in New York, is the co-author of Frank Lloyd Wright in New York: The Plaza Years, 1954–1959 (2007, Gibbs Smith) and served on the board of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy for six years. In 2011, she wrote “Remembering Edgar” in memory of her friend and Wright apprentice, Edgar Tafel.

——————————–

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico7.blogspot.com

https://onlybook.es/blog/frank-lloyd-wright-some-key-stages-of-his-life-part-3-mbgb/