hugoklico Deja un comentario Editar

«35 rue de Sevres, one hundred years». Publication (very good) of the magazine ARQUINE on September 18, 2024.

By Alejandro Hernández Gálvez | Twitter: otrootroblog | Instagram: otrootroblog

Perhaps there is no other mythical address in modern architecture with the weight of 35 rue de Sèvres in Paris.

It was there that on September 18, 1924, 100 years ago today, Le Corbusier established his workshop, according to the foundation that bears the name that Charles Edouard Jeanneret-Gris gave himself.

The rue de Sèvres was first called de la Maladrerie, then Petites-Maisons, because of a hospital for lepers, closed under François I and in whose place the Petites-Maisons were built. Beggars, people of bad habits, and madmen were locked up there; however, the establishment was divided, leaving mainly a hospital.

From 1355 there is news of the name street or road of Sèvres, as it was the direction to that city, southwest of Paris, today famous for the National Porcelain Manufacture that was established there in 1756 – and that from 1800 to 1847 was directed by Alexandre Bronginart, among other things, son of an architect, chemist and mineralogist, and collaborator of Georges Cuvier, with whom he carried out pioneering studies in stratigraphy, such as his «Theoretical Court of the Parisian Basin»—and the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, founded in 1875, where the «universal standards» of the meter and the kilogram are preserved.

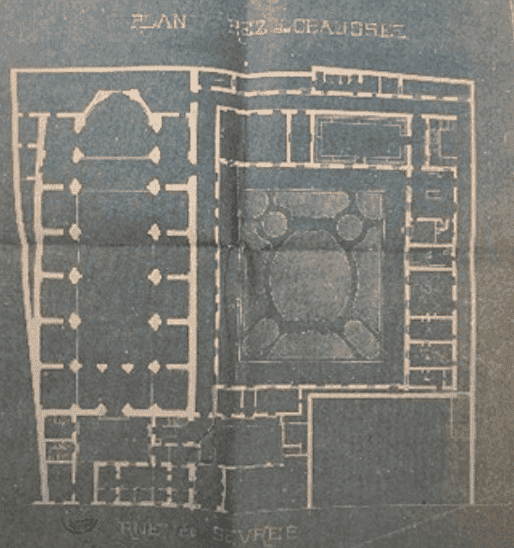

It was shortly after 1821 that the Society of Jesus bought the buildings located at numbers 33 and 35 rue de Sèvres. Then they would add those of numbers 37 and 43. Between 1855 and 1858 the church of San Ignacio was built, which was followed by a cloister. The last building built on these grounds by the Jesuits, after a complicated history of expulsions and returns of the Society in France, was a study center inaugurated in 1974.

José Ramón Alonso Pereira writes that it was Winaretta Singer-Polignac who, at the beginning of the summer of 1924, offered Le Corbusier the possibility of setting up his studio, «under very advantageous conditions», in a secondary space occupied by the gallery on one of the cloistered sides of the Jesuit Residence. He also says that both the temple of Saint Ignatius and the building of the residence were designed by Jean-Maggior Torunesac, «diocesan architect later a Jesuit, who followed the ogival style of Le Mans Cathedral.» Of Winaretta Singer-Polignac he writes:

She was the daughter of the famous American industrialist Isaac Merrit Singer, whose name was the emblem of the sewing machine. Born in New York, she lived in England and Paris, where she learned to paint and became interested in Impressionist creations, as well as in the English Pre-Raphaelites, admiring in them their attempt to merge literature, philosophy, religion and history. She married Louis de Scey-Montbéliard at the age of 22 and then Prince Polignac, whose union was based on mutual respect and a great artistic friendship, especially for music.

The salons of his house in the Trocadèro – decorated by the famous José María Sert, uncle of the architect José Luis Sert, later an apprentice to Le Corbusier – were known as an important avant-garde musical centre. The best performers of their time played there: Gabriel Fauré, Claude Debussy, Eric Satié, Maurice Ravel, Igor Stravinsky, Arthur Rubinstein, Manuel de Falla, etc.

It is known that many of Marcel Proust’s evocations of the culture of the time were born from his attendance at those concerts in the Polignac salon. Winaretta Singer also used her fortune to promote the arts and sciences, with a manifest social component linked to her militant Christianity. In particular, he was a patron of the Armée de Salut, 49 sponsoring Le Corbusier’s projects: the annex to the Palais du Peuple (1926-27), the Floating Asylum (1930) and the Cité de Refuge (1929-33).

Alonso Pereira underlines Le Corbusier’s interest in naming his workplace a «workshop» and not an «architecture agency», as was customary – that was the name of Perret’s, with whom he worked – or «office», leaning towards the use of «atelier» by artists.

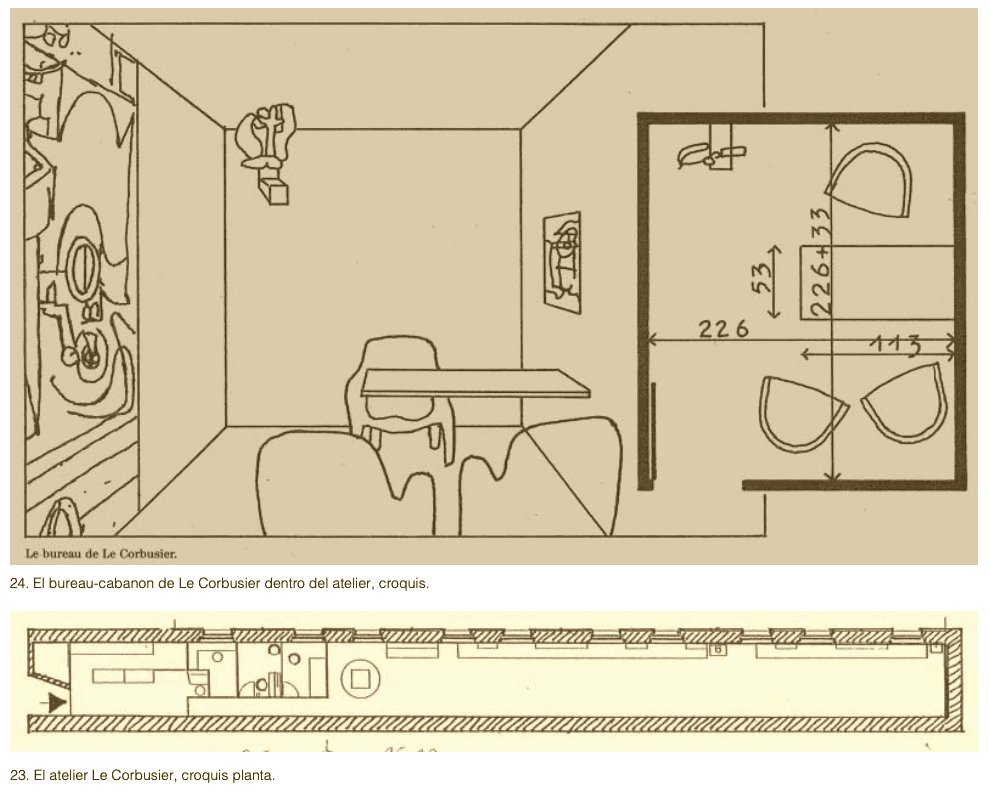

About the space itself, Alonso Pereira writes: «With a height of 4 meters, the premises measured 41 meters long by 3.50 meters wide. That is to say, it had a ratio of 1 to 12, a very thankless ratio that was only matched by one work in the history of architecture: the gallery that forms the entrance to the Vatican palaces defining the straight arm of Bernini’s St. Peter’s Square, a work admired by Le Corbusier a few years earlier, during his second trip to Rome with Ozenfant in the summer of 1921. In it you can see a more or less clear antecedent of the Sèvres atelier as an architectural space.»

«Located on the first floor of the convent building, it was not easy to find the premises of the atelier. The access process was as follows. Common to that of the church, the entrance to it from the street was an atrium lit by a skylight, with doors open in all directions. The only indication of the atelier was a small blue plaque with a handwritten sign in red: «Atelier Le Corbusier, first floor at the end of the corridor.» The door on the right was opened, and one passed into the northern corridor of the cloister, illuminated by the light from the south, which led at the end to a wooden staircase that ascended to the first floor. Once up the stairs you crossed the door of the sanctuary. A photographic mural and a black door gave way to the atelier»

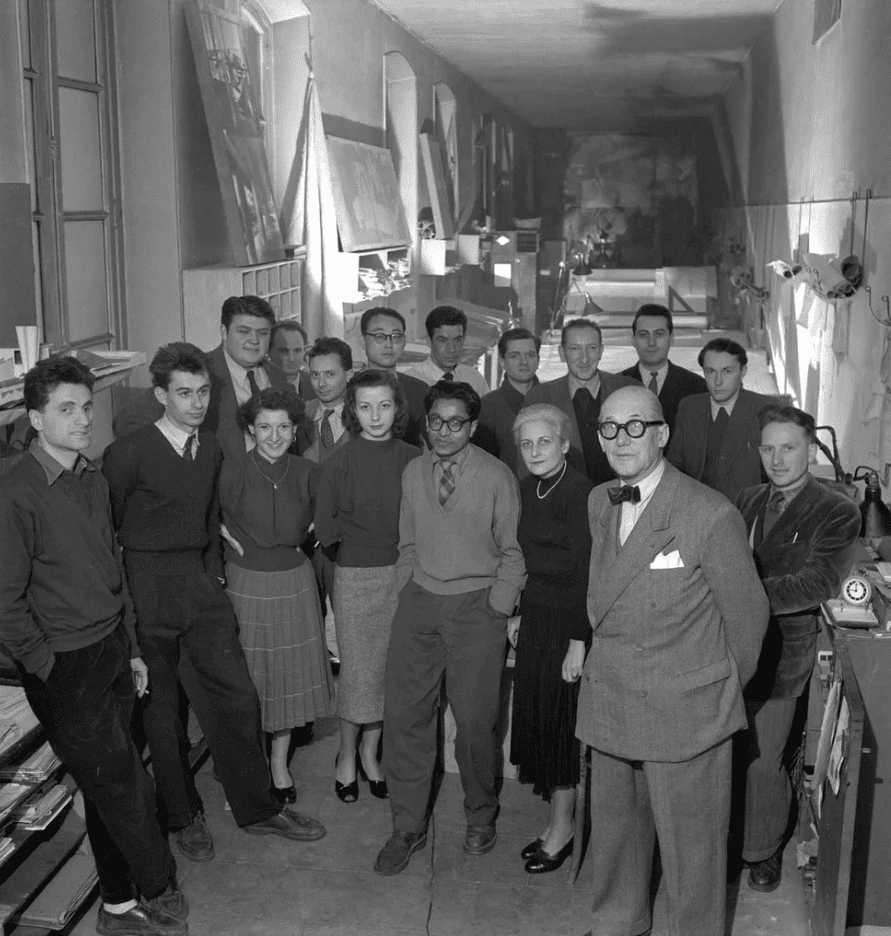

«Ten high windows looked out over the cloister and its centenary trees. In 1924 Le Corbusier closed the two ends of the premises with brick walls. In the early days, the atelier was only furnished with a few chairs and drawing tables on easels, in no order, and the equipment was reduced to what was strictly necessary: a telephone and a stove, since the gallery had no heating. Then some screens were set up so that Le Corbusier could have a personal corner 53 to receive.»

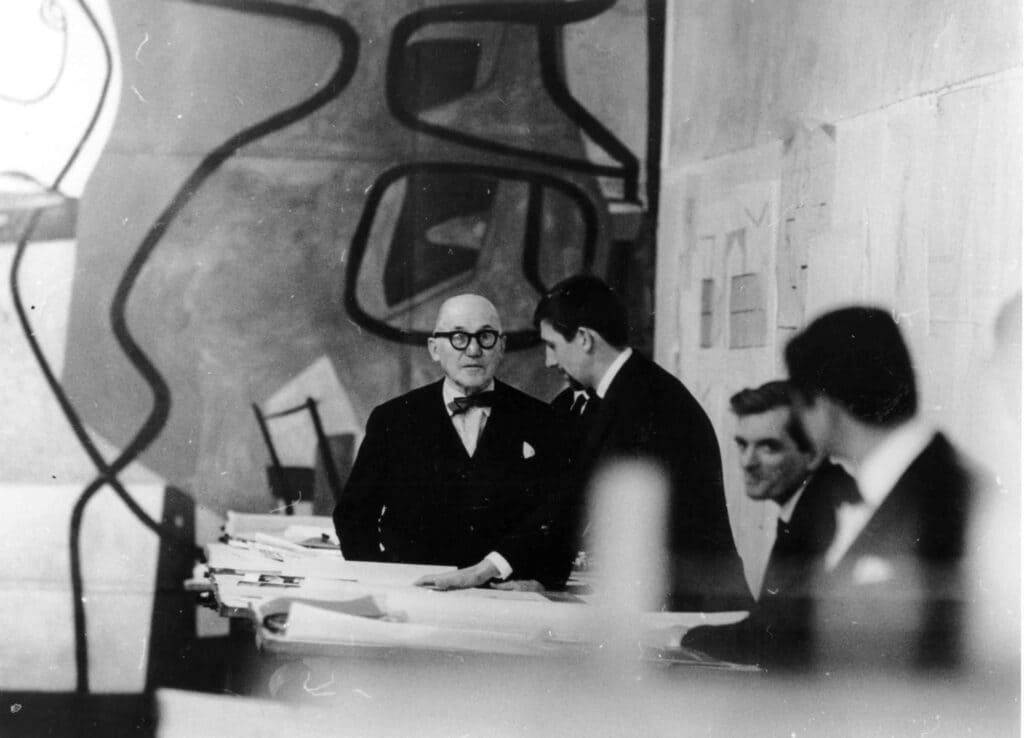

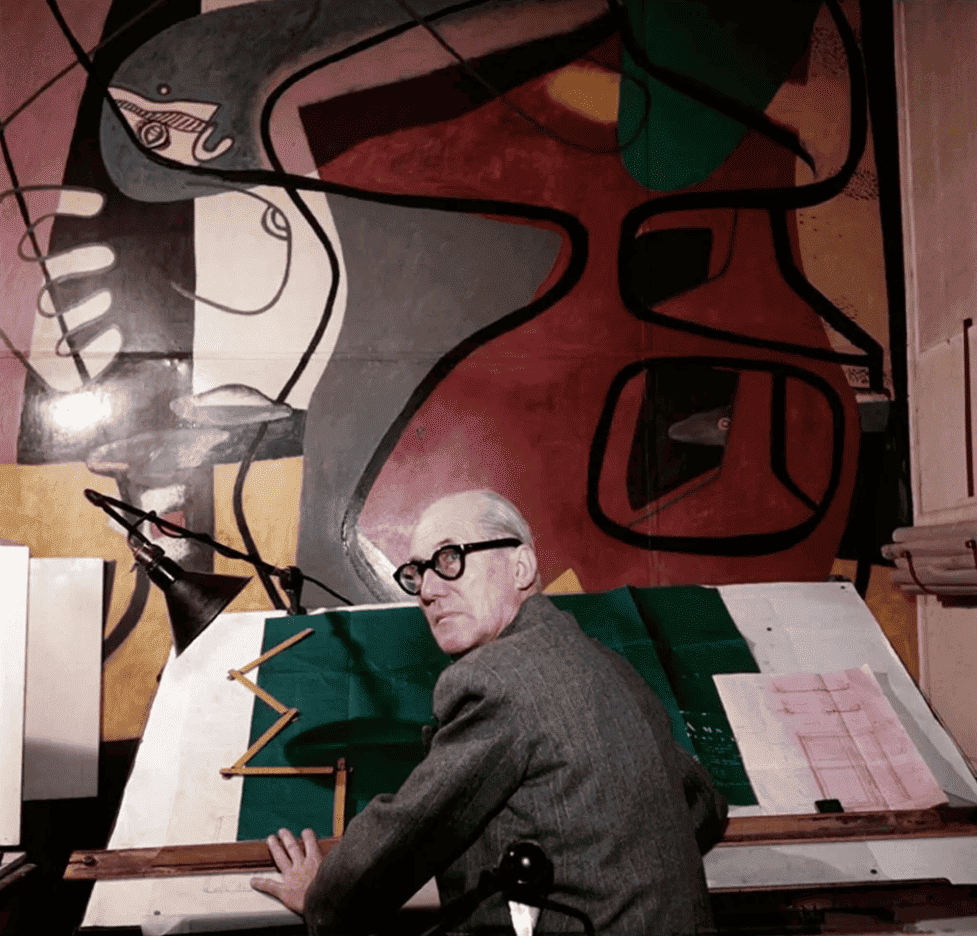

As for the space, the atelier was organized in three concatenated sections. The first was a dark body, without natural lighting, where the areas of access, storage and copying of plans, control and secretarial were located, followed by the small offices of Le Corbusier and, at the time, of the head of the atelier, behind which the atelier itself opened, with the tables and drawing boards, at the bottom of which there would be a large mural painted by Le Corbusier since 1947.

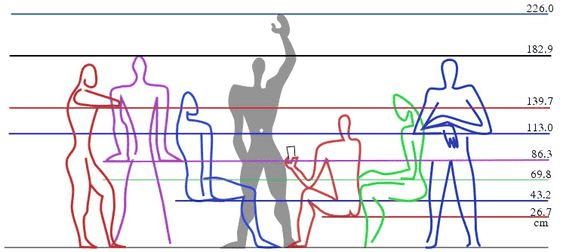

At the entrance, a small lobby, to the left of which were placed the changing rooms and the copier of plans, concealed by filing cabinets, and then the secretarial office that controlled the entrance. Behind it was Le Corbusier’s small bureau, an office of 2.59 × 2.26 × 2.26: a ‘standard volume’ that gave plastic expression to the concepts of the Modulor, whose publication was being prepared at the time. This mythical bureau was like a cabanon, an interior architecture within an enveloping architecture.

Another description, less objective, perhaps, but certainly closer, is the one made by Charlotte Perriand: «… My footsteps regularly took me to the rue de Sèvres until 1937. My unexpected role was to collaborate as an associate of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in the development of their furniture program: «drawers, chairs and tables», which they had announced in 1925 in the pavilion of the Esprit Nouveau, to continue their study and ensure the execution of the prototypes by my artisans, but also to initiate myself in architecture, as I wanted, because everything is linked. Working in this old convent, now demolished, was a privilege. It was an inspired place. After the concierge booth, we enter a wide corridor to climb the first flight of stairs. At the top left was the entrance to the workshop. Once through the gate, we find ourselves in a vast camp. A rope ran along an endless wall where the drawings hung from clothespins.»

The high windows looked out onto the courtyard of the convent. In the center of the workshop, a solitary wood-burning stove. No independent secret office. The mail was placed on one of the drawing tables. Everyone could read it. In summer we heard the birds singing, in winter we froze to death (then I wrapped my legs in newspaper so I wouldn’t feel my feet freezing). Let us think of this heroic, pioneering and penniless age, with so few means, let us think of all these architectural or urban projects never realized and yet carefully studied, which go far beyond the object itself, projects in relation to man, in harmony with him, in accordance with his times. Because, after all, why our work if not that? The result is visible and experienced. It can make man happy or unhappy, according to his honest conception. It creates the nest of man and the tree that will sustain it. We end up believing it.

Boys, young people, enthusiasts, coming from the best schools, from all over the world, were there, not only for the architecture, but for Corbu, for his way of solving all problems, for his aura. Corbu had chosen France to express himself, but France had not adopted him. Academicism reigned. The rejection of the other was mutual, the struggle, even unjust, was necessary. Corbu would never have accepted a student from the École des Beaux-Arts into this studio on rue de Sèvres: their drawings were bad, their minds were distorted. This was one of the reasons why he preferred to hire Jean Bossu, whose motivation was to be an architect and who worked as a night stevedore in Les Halles. However, Corbu did not spare him his criticism, as he did ourselves, and even his bad mood, until the day Bossu left us to practice his profession in total freedom. In this Tower of Babel we spoke all languages, French badly, but we spoke the same language.We helped each other with the frequent «sudden», there were not many of us. Those days, the effervescence began after Corbu’s departure, at eight in the evening.

Corbu left 35 rue de Sèvres for the last time on Wednesday, July 28, 1965. The atelier closed for holidays and Le Corbusier left to rest in his cabin in Cap Martin. On Friday, August 27, Le Corbusier died while swimming in the Mediterranean. Alonso Pereira writes: his remains returned to Paris, to the atelier of Sèvres, opened for the last time to receive him.

La Vanguardia, August 28, 1965.

The architect who has just died has been in the interwar years a fabulous gravedigger of concepts, forms, masses, ornaments… He was a winner and a more or less official failure. Let us remember in this regard the palace of the League of Nations, in eighteenth-century style that made the conservatives so happy to witness how Le Corbusier’s project was postponed because it was too audacious. But the creator of rational architecture had to say some profound words in that trance «… The Palais des Nations is no longer, as was intended, a work machine, but a mausoleum representative of all that is terribly useless and incapable of evolution that an Academy represents».

Le Corbusier, if he retains his original prestige, owes it simply to the fact that he never built a mausoleum. A. R. ©Newspaper Library La Vanguardia de Barcelona.

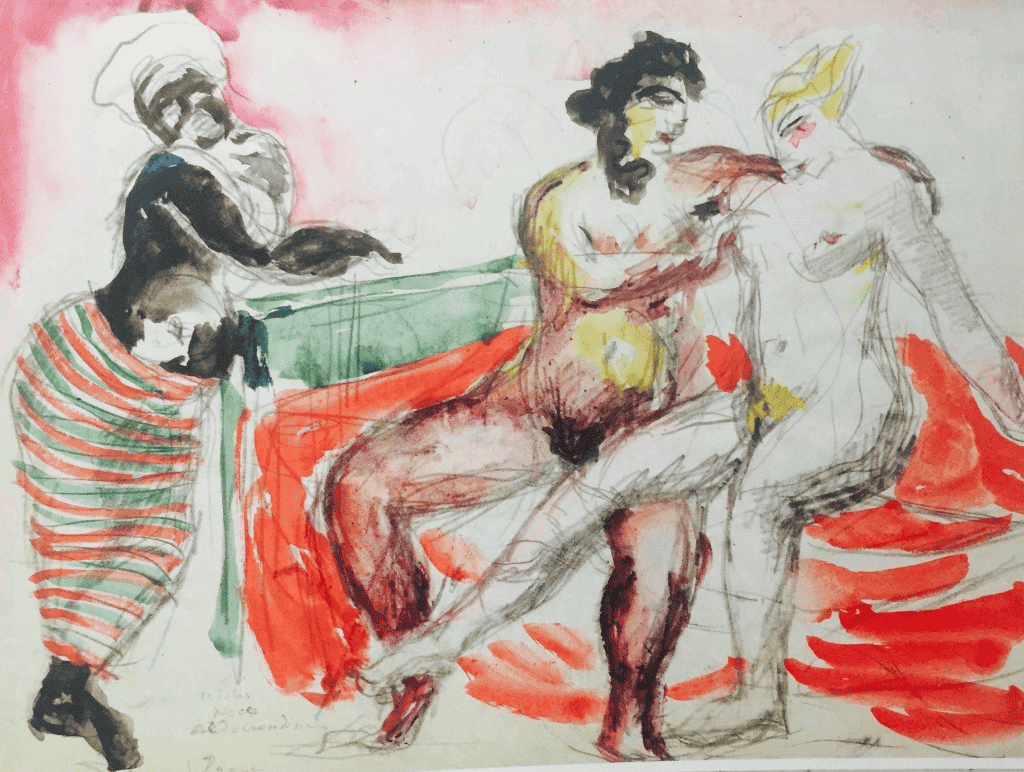

See Sketches de Le Corbusier https://onlybook.es/blog/sketches-de-le-corbusier-viaje-a-oriente-y-burdeles-de-paris/

See El Modulor https://onlybook.es/blog/el-modulor-de-le-corbusier/

—————————————————————

Our Blog has obtained more than 1,300,000 reads.

http://onlybook.es/blog/nuestro-blog-ha-superado-el-millon-de-lecturas/

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico.blogspot.com

Salvemos al Parador Ariston de su ruina

http://onlybook.es/blog/el-parador-

Post navigation

Entrada anteriorAlberobello, Polignano a Mare, Ostuni, Matera en La Puglia. (mb)Entrada siguienteFoster en las palabras de Luis Fernandez Galiano. Fundación J. March