hugoklico Deja un comentario Editar

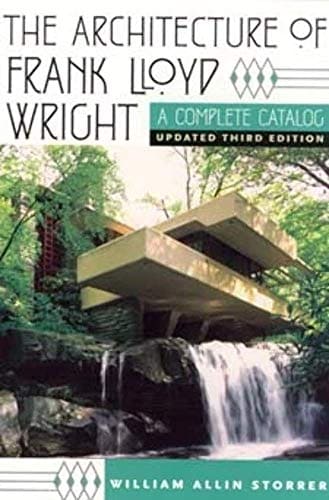

For many of my articles I use renowned scholar William Allin Storrer’s classic book The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: A Complete Catalogue as it is the authoritative guide to all of Wright’s built work. This updated third edition reviews each of Wright’s structures, tracing the architect’s development from his works on the Prairie, through to the final building constructed, the magnificent Aime and Norman Lykes Residence in California (S.433).

William Storrer incorporates a number of key revisions and tells the story of each building up to the present day, as some buildings have been remodeled, some moved, and others sadly abandoned or destroyed by natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina, including the James Charnley Bungalow in Ocean Springs, Mississippi.

Organized chronologically, this updated third edition features color photographs of all extant works along with a description of each building and its history, with complete addresses, GPS coordinates, and maps of locations throughout the United States, England, and Japan, indicating the shortest route to each building.

Some stages of his life 1885–1887

In 1886, at age 19, he was admitted to the University of Wisconsin-Madison and worked with Allan D. Conover (1854 – 1929) as a professor of civil engineering, leaving school without earning a degree.

According to campus records, Wright spent only two semesters at the UW University of Wisconsin-Madison there he studied civil engineering briefly, never graduating. (1)

In his biography Wright corrects that he stayed 2 semesters, he has written that he left school after three and a half years.

Wright attempted to submit what he called his senior thesis at age 88, the UW administration rejected his offer but instead awarded him an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts in 1955, a distinction given for outstanding achievement.

1941 and 1953

Frank Lloyd Wright received several honorary doctorates. Among the universities that awarded him this distinction were:

-University of Wisconsin-Madison (1955), although an exact transcript of his speech does not survive, but it has been written that Wright joked about his college experience and said, «I never finished my studies here, but it seems that now you have decided to correct that mistake.»

-Also Princeton University (1947)

In 1941 he received the Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

In 1949 the American Institute of Architects awarded him the AIA Gold Medal. The medal marked a symbolic “burying of the hatchet” between Wright and the AIA. In a radio interview he commented: “Well, I never joined the AIA, and they know why. When they gave me the gold medal in Houston, I told them frankly why. Thinking that the architectural profession is the only thing wrong with architecture, why would I join them?”

In 1953 he was awarded the Frank P. Brown Medal from the Franklin Institute.

Among the reasons mentioned in many of the distinctions awarded to him are:

-His contribution to organic architecture, which seeks to integrate buildings with their natural surroundings and human needs.

-His influence on the Modern Movement worldwide.

-Many of his buildings are icons in redefining architecture (such as Fallingwater or the Guggenheim Museum).

-His contribution to education with his Taliesin Foundation.

1886

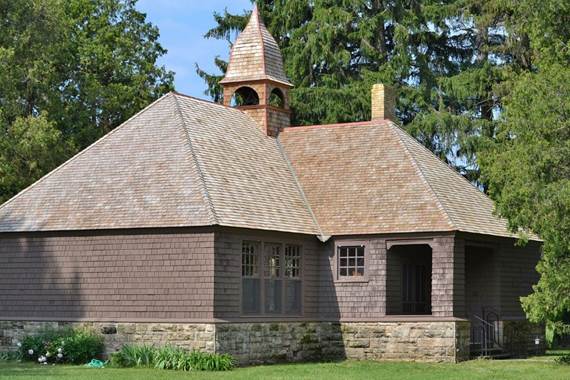

Wright collaborated with the Chicago architectural firm of Joseph Lyman Silsbee (1848 – 1913) where he worked as a draftsman and construction supervisor on the 1886 Unity Chapel for his uncle, the Unitarian minister Jenkin Lloyd Jones, in Spring Green, Wisconsin.

Wright also worked on two other family projects: All Souls Church in Chicago for his uncle, Jenkin Lloyd Jones, and Hillside Home School I in Spring Green for two of his aunts.

Silsbee left behind notable works such as the White Memorial Building in Syracuse from 1896 or The Amos Building in downtown Syracuse, NY.

He was paid only $8 a week so he quit to work for the firm of Beers, Clay, and Dutton, when Joseph Silsbee offered him a raise, and he returned to him, since he taught Wright what he needed for his training.

1888 1893

Adler & Sullivan were looking for “someone to do the final drawings for the interior of the Auditorium building.” After two brief interviews he was appointed an official apprentice at the firm. Wright did not get along with Sullivan’s other draftsmen; He wrote that several violent altercations occurred between them during the early years of his apprenticeship. Sullivan apparently did not treat them well either.

«Sullivan took Wright under his wing and gave him a great deal of responsibility in the design.» As an act of respect, Wright would later refer to Sullivan as Lieber Meister («Dear Master»). He also formed a bond with office foreman Paul Mueller. Wright later hired Mueller to build several of his public and commercial buildings between 1903 and 1923.

1887

Wright came to Chicago in search of employment. As a result of the devastating Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and the population boom, new developments were abundant.

By 1890, Wright had an office next to Sullivan’s that he shared with his friend and draftsman George Elmslie, who had been hired by Sullivan at Wright’s request. Wright was already chief draftsman and did all residential design work in the office.

Louis Sullivan dictated the guidelines for these residential projects (2). Wright’s design duties were often limited to detailing the projects from Sullivan’s sketches.

During that time, Wright worked on Sullivan’s bungalow (1890) and James A. Charnley’s bungalow (1890) in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, the Berry-MacHarg House, the James A. Charnley House (both 1891), and the Louis Sullivan House (1892) in Chicago. The Walter Gale House, Oak Park, Illinois (1893).

Pirate Houses, the Beginning of the Break with Sullivan

Despite Sullivan’s loan and overtime pay, Wright was constantly short of funds. Wright admitted that his poor finances were probably due to his expensive tastes in clothing and vehicles, and the additional luxuries he designed in his home. To supplement his income and pay his debts, Wright accepted independent commissions for at least nine houses. These “pirate houses,” as he later called them, were conservatively designed in variations of the fashionable Queen Anne and Colonial Revival styles. Eight of these early houses remain today, including the Thomas Gale, Robert Parker, George Blossom, and Walter Gale houses.

Sullivan was unaware of the detached works until 1893, when he recognized that one of the houses was undoubtedly a Frank Lloyd Wright design; this particular house, built for Allison Harlan, was just a few blocks from Sullivan’s townhouse in Chicago’s Kenwood community.

See https://onlybook.es/blog/gb-the-integral-design-of-frank-lloyd-wright-mbgb/

Apart from the location, the geometric purity of the composition and the balcony tracery (the decorative element made up of combinations of geometric figures) in the same style as Charnley House probably betrayed Wright’s involvement. Since Wright’s five-year contract prohibited any outside work, the incident led to his departure from Sullivan’s firm. Various stories recount the breakdown of the relationship between Sullivan and Wright; Wright later told two different versions of what happened.

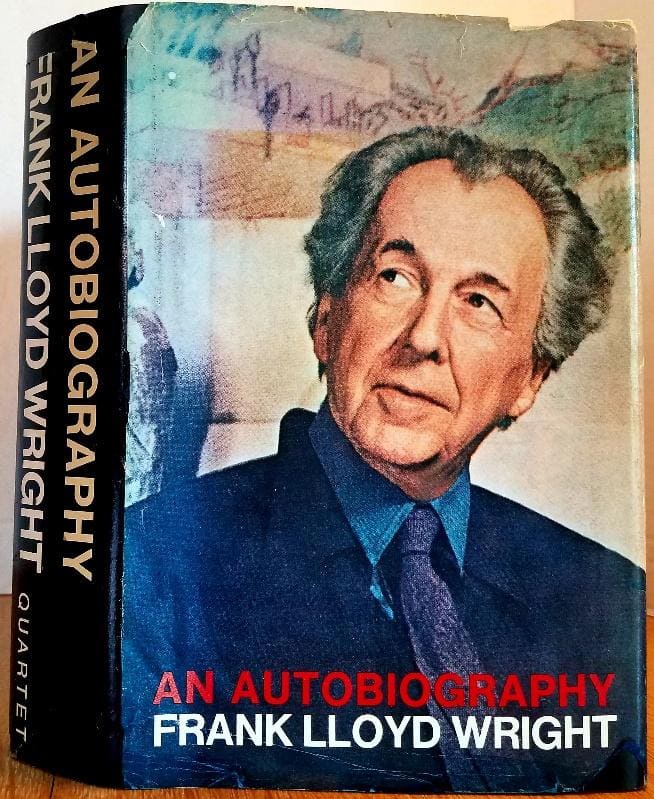

In An Autobiography, he claimed that he was unaware that his side affairs were a breach of his contract. When Sullivan learned of them, he became angry and offended, forbade him to take any more outside assignments, and refused to grant Wright the deed to his Oak Park house until after he had completed his five years. Wright could not stand his boss’s new hostility and thought the situation unfair. “…he threw down [his] pencil and walked out of the Adler & Sullivan office, never to return.” Dankmar Adler, who was more sympathetic to Wright’s actions, later sent him the deed. However, Wright told his Taliesin apprentices (as recounted by Edgar Tafel (1912–2011)) that Sullivan fired him on the spot upon learning of Harlan House. Tafel also recounted that Wright had Cecil Corwin sign several of the pirated works, indicating that Wright was aware of their forbidden nature. Regardless of the correct series of events, Wright and Sullivan did not meet or speak for 12 years.

1892

Chicago, IL. Destroyed by fire in 1963. According to Wright, the Harlan House marked the true beginning of his career.

He felt that his design was unaffected by outside influences, and indeed the house featured many innovations that would become distinctive features of his residential work.

The building was oriented toward the northern periphery of the lot to maximize its exposure to natural light on the south.

Wright employed corbels to support the house’s second-floor balconies, and a series of large windows in the building’s first-floor living room opened onto a terrace. The balconies featured decorative tracery reminiscent of that found on the Charnley House.

1893–1900

After leaving Adler & Sullivan, Wright took up residence on the top floor of the Sullivan-designed Schiller Building on Randolph Street in Chicago in 1890/1891.

Cecil Corwin followed Wright and took up residence in the same office, but the two worked independently and did not consider themselves partners.

1930

Wright visited Princeton University many times throughout his long career. The first and perhaps most important visit was in 1930, when Wright accepted the Kahn Professorship and gave a series of six illustrated lectures in McCormick Hall. Modern Architecture; Being the Kahn Lectures for 1930, was published the following year by Princeton University Press (who still have six copies of the original), and he designed its cover.

The Princeton University Weekly Bulletin (May 3, 1930) announced that “From May 3 to May 14, Frank Lloyd Wright will present a series of lectures on the problems of modern architecture… Today he will speak on the subject of “Machinery, Materials, and Men,” and tomorrow on “Style in Industry; The War of Styles.”

On Thursday, “The Cardboard House,” and his closing address for the week on Friday, “The Disappearance of the Cornice,” will address a trend in architecture.

In a week, he will speak on “The Tyranny of Skyscrapers,” and will end his series with a talk entitled “The City.”

Wright exhibited recent drawings at the Museum of Historical Art, a space that housed the Department of Art and Archaeology, the Fine Arts Library, and the School of Architecture. Then the exhibition entitled “The Show,” which included 600 photographs, a thousand drawings, and four models, would go on to New York; Chicago; Eugene, Oregon; Seattle, Washington; then to several European cities; and the Layton Gallery in Milwaukee.

1933

In the spring of 1933, another exhibition was held at McCormick Hall, entitled Early Modern Architecture: Chicago 1870-1910.

This show, prepared by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, featured wall labels by Philip Johnson (1906 – 2005), chairman of the Museum’s Department of Architecture, and Professor Henry Russell Hitchcock (1903 – 1987) of Wesleyan University.

1947

Wright returned to Princeton for a two-day conference in connection with the University’s bicentennial celebration. “Planning Man’s Physical Environment” brought together 70 architects, urban planners, philosophers, and social psychologists under the direction of Arthur C. Holden (1890 – 1993).

He advocated decentralization of American cities, telling students: “We are educated far beyond our capacity. We have urbanized urbanism into a disease: the city is a vampire living off the fresh blood of others, sterilizing humanity.”

1955

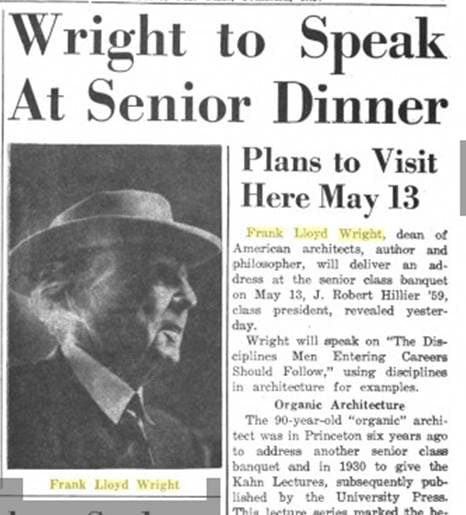

In 1955, Wright was invited to be the keynote speaker at that year’s senior class dinner. He gladly accepted, but at the last minute asked that the dinner be rescheduled while he attended to construction problems with the Guggenheim Museum building. The 800 students and their guests accepted him, and his talk was so memorable that the class of 1959 invited him back, but Wright died a month before the Princeton event.

“An expert is a man who has stopped thinking: he knows.” F. Ll. W

Notes

1

Academia Lab. (2025). Frank Lloyd Wright. Enciclopedia. https://academia-lab.com/enciclopedia/frank-lloyd-wright/

2

Frank Lloyd Trust

———————————————

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico.blogspot.com

Previous entry GB. The works of Frank Lloyd Wright. Tom Monagham, the Wasmuth Portfolio and Murder at Taliesin, part 5. (mbgb)