Previus text read https://onlybook.es/blog/frank-lloyd-wright-some-key-stages-in-his-life-part-4-mbgb/

The Caravan from Taliesin East to Taliesin West

3,500 km from Wisconsin to the Arizona Desert

Frank Lloyd Wright began building Taliesin West in 1937, at the age of 70, as a winter residence for himself and Olgivanna. The property occupies approximately 240 hectares of the Sonoran Desert and was located an hour from Phoenix, the nearest major city, when it was purchased.

On the Road with Frank Lloyd Wright

On June 8, 2017, Patrick Sisson (8) tells us on his “Curbed blog” and on his “On Tour with Frank Lloyd Wright” page what the road trip to Taliesin in Arizona was like.

The caravan of 30 people left Spring Green, Wisconsin, on January 23, 1935, in several cars and a red pickup truck, heading for the Arizona desert, a desert many of them had never seen before.

At that time, during the harsh winter, when the temperature was 40 degrees below zero and the roads were canyons carved out of drifts of snow…anywhere else would have been a better destination. It was the time of the economic depression…they were equipped with supplies, drawing materials, and architectural models. The 3,500-kilometer journey that Frank Lloyd Wright and his apprentices undertook to Arizona that winter represented a new chapter in his career.

Near Dodgeville, they stocked up on supplies at Etta Hocking’s grocery and butcher shop, the trip heading west on a primitive, mostly unpaved version of Route 66 (…) stopping at budget hotels and tourist cabins, eventually ending at a site near what would become the architect’s famous Arizona home and studio, Taliesin West.

This was the beginning of the migration. They called it «the journey,» or «hegira,» which in Arabic means «flight or emigration.»

The semiannual trip became a ritual for the architect and his apprentices. While he didn’t write or speak much about the trips, his apprentices did in books and journals, it became a synthesis of Wright’s passion for architecture, automobiles, and the American landscape.

Landscape architect and professor Anne Whiston Spirn wrote in the book Frank Lloyd Wright: Designs for an American Landscape:

“Perhaps Wright’s tendency to idealize both Taliesins was fueled by his periods of absence and the fact that he spent the most pleasant seasons at each; they came to resemble summer cabins and winter encampments rather than year-round dwellings.”

Gene Masselink, Wright’s longtime personal secretary, recalls the end of that 1935 Arizona trip, as the wagon train vehicles “were coming down from the mountains as the sun neared the horizon.” He marveled at the landscape before him: the “tall, graceful saguaro (plant), with white blossoms and edible fruit, and the waving ocotillos (native plant) illuminated by long, low beams of sunlight. It was “a desert such as I had never dreamed of.” From the ocotillo plant, Wright, modifying a letter, named his first camp Ocatillo.

You can read more about the camp in detail at https://onlybook.es/blog/frank-lloyd-wright-some-relevant-stages-of-his-life-part-4-mb/

These trips began at a time when cross-country driving was still long and difficult (the first continental highway, Route 30, was completed in 1925).

On the Road with Frank Lloyd Wright

A group of architects followed a circuitous route, often dictated by Wright, who, aboard one of his elegant convertibles, sports cars, or coupes, such as the majestic Jaguar Mark IV, traveled across the country at top speed. With occasional stops at sites designed by Wright, these road trips to and from the desert camp allowed him to observe firsthand the country’s changing landscape and how automobiles were transforming society.

It was certainly a recurring theme in his work, as he designed numerous automotive-influenced structures, including a gas station, a service station/restaurant, a butterfly-shaped bridge, a drive-through national bank, a self-parking garage, and his Jaguar showroom in New York City.

In 1935, Chandler invited Wright to stay at the Hacienda, a polo stable converted into a hotel, to escape the harsh winter of that year and work under the desert sun.

The architect had founded his Taliesin Fellowship, an apprenticeship program for aspiring architects, in 1932 and decided to bring the entire group. During their stay, Wright and the apprentices would develop their concept of Broadacre City, Wright’s vision of a rural, suburban, automobile-centric lifestyle. The apprentices, who built a huge wooden model of the project outdoors during the day, slept in sleeping bags at night.

In 1937, Wright founded a school of architecture at Taliesin West, where students, called «Fellows,» lived and studied.

You can read https://onlybook.es/blog/las-obras-de-frank-lloyd-wright-parte-12-conferencias-en-princeton-y-la-casa-walker/

The round trip to Arizona that year would set the pattern for Wright’s annual migration. On the way west, frugality reigned.

Wright bought and drove cars that he believed embodied intelligent design, elegance, and good performance. Among them were brands such as Jaguar, Packard, Cadillac, and Mercedes-Benz.

He also owned a 1937 AC 16/80 Competition Sports; five 1949 Crosleys; two Cord L-29s (Phaeton and Cabriolet); a 1953 Bentley R-Type convertible and, famously, a modified 1940 Lincoln Continental. Like many of the objects in his professional and personal life, his cars were painted his favorite Cherokee Red (a shade he called «the color of creation»), including the AC and the Crosleys.

About the color Cherokee Red you can read https://onlybook.es/blog/frank-lloyd-wright-algunas-etapas-relevantes-de-su-vida-4ta-parte-mb/

Of all his cars, the AC 16/80 and the Hot Shots are significant, specifically because Wright incorporated them into his teaching and his students used them on trips across the country during the 1950s.

Wright kept his cars in numerous locations, including his two residences, Taliesin East in Spring Green and Taliesin West in Scottsdale.

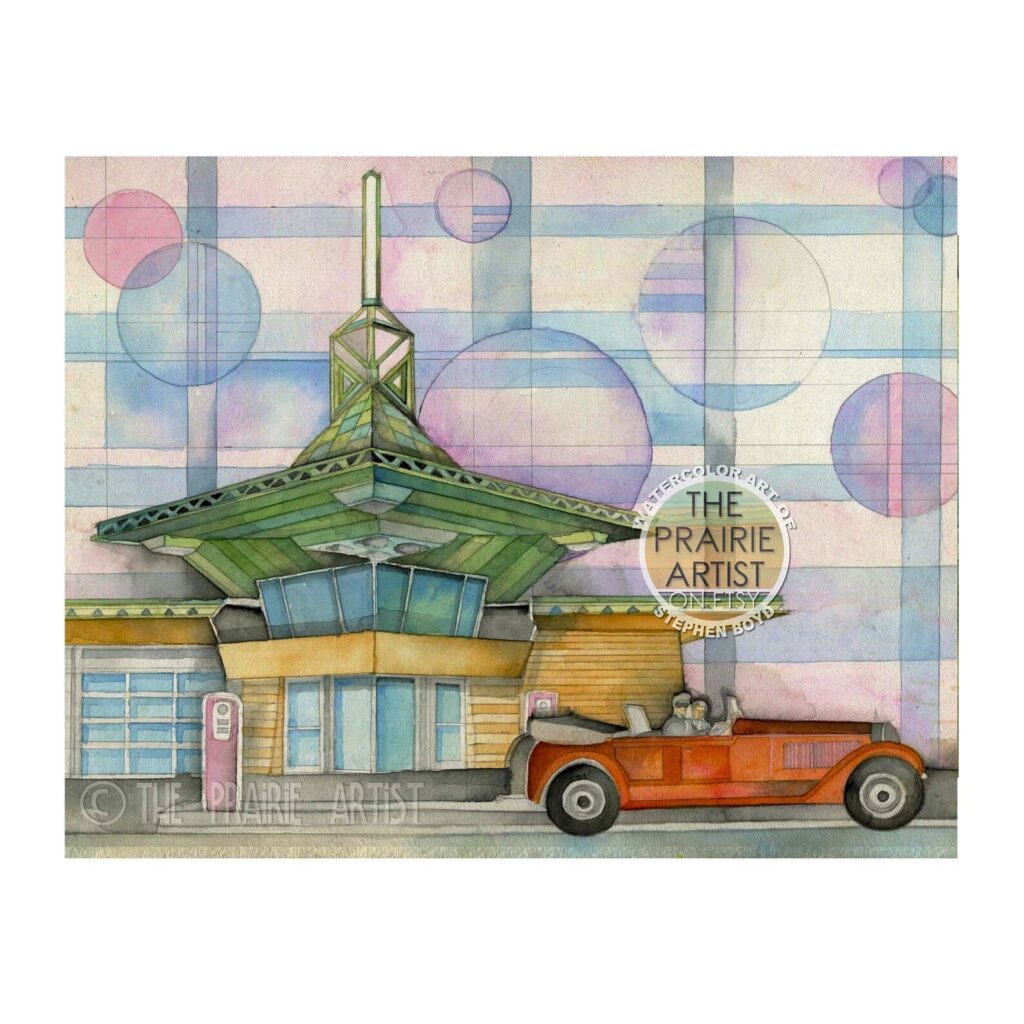

The Lindholm Service Station. 1958

The RW Lindholm Gas Station is a Wright-designed gas station in Cloquet, Minnesota.

Built in 1958 and still in use, it is the only gas station built during Wright’s lifetime.

It was originally part of the utopian plan for Broadacre City and is one of the few designs from that plan that was implemented.

On September 11, 1985, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Wright had designed the home of Ray Lindholm, the owner of the gas station, in 1952 and, knowing that Lindholm worked in the oil industry, presented him with a proposal to design the gas station he had envisioned as part of Broadacre City.

Let’s look at «Mäntylä,» Lindholm’s house. 1952

Originally built at Route 33 and Stanley Avenue in Cloquet, Minnesota, it was moved to Polymathe Park, located 20 miles from the Fallingwater house and near the Kentuck Knob house.

The RW Lindholm House, often called Mäntylä, Finnish for «house among the pines,» was built in 1952 in the small town of Cloquet, in northeastern Minnesota.

Designed for Ray and Emmy Lindholm, it is an example of one of Wright’s late Usonian houses, created for middle-class families beginning in the 1930s during the Great Depression.

The low-slung dwelling, approximately 2,250 square feet (2,140 square meters), based on 4-foot modules, was built of concrete block and has a roof clad in Ludowici reddish tiles. The beams are standard wood, and cypress wood was used for the window frames and built-in furniture.

The garage is more enclosed than is typical in Wright’s projects.

The clients’ grandson, Peter McKinney, and his wife, Julene, eventually became owners of the Lindholm House, where they lived for many years.

When they decided to put it up for sale, they found no buyers.

In 2016, they began collaborating with the Chicago-based Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy to determine how to ensure the home’s longevity.

Its isolated setting had changed significantly over the decades, and noisy, brightly lit commercial development dominated the area.

“The McKinneys and the Conservancy concluded there was no viable long-term future for the house as a residence on its once isolated, wooded property,” so they ultimately decided to donate it to an organization that owns a 130-acre (53-hectare) estate in Acme, Pennsylvania, called Polymath Park, 60 miles (96 km) from Pittsburgh.

Barbara Gordon, the Conservancy’s executive director, said moving the house to the Pennsylvania property was the best option.

In 2016, they began collaborating with the Chicago-based Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy to determine how to ensure the home’s longevity.

Its isolated setting had changed significantly over the decades, and noisy, brightly lit commercial development dominated the area.

“The McKinneys and the Conservancy concluded there was no viable long-term future for the house as a residence on its once isolated, wooded property,” so they ultimately decided to donate it to an organization that owns a 130-acre (53-hectare) estate in Acme, Pennsylvania, called Polymath Park, 60 miles (96 km) from Pittsburgh.

Barbara Gordon, the Conservancy’s executive director, said moving the house to the Pennsylvania property was the best option.

Thousands of pieces were transported, including interior walls made from hundreds of individual planks.

The components traveled more than 1,609 kilometers to the new location. Reconstruction began in 2018 and was completed in 2020.

Both the exterior and interior have remained faithful to the original design, with its enormous windows and glass doors over 3 meters high.

The Conservancy organizes daily tours.

Lindholm Service Station

In his original plans for Broadacre City, Wright designed his service stations to be community social centers and an integral part of his utopian ideas. His design for the Lindholm Service Station reflects these plans and represents an unconventional approach to service station design at the time.

Lindholm took the opportunity to embellish the station’s design, and the design was completed in 1956. The station ultimately cost $20,000, about four times the average cost of a gas station at the time.

It opened in 1958 under the Lindholm name; it later became a Phillips 66 station.

Its construction was only a partial success for Wright, as his vision of the station as a social center never materialized. However, Phillips 66 incorporated several of the station’s design elements, notably the cantilevered triangular canopy, into later stations. Since 2014, it has operated under the Spur brand. In 2018, Ray Lindholm’s grandchildren sold the station to developer Andrew Volna for $250,000.

A cantilevered copper canopy extends over the gas pumps. Although Wright had planned to install gas pumps suspended from the canopy to create more space in the service areas, local safety regulations forced him to install conventional pumps on the ground.

I saw the hoses for the suspended pumps at the gas station, also by Wright, at the Pierce Arrow Museum in Buffalo.

Beneath the canopy is a glass-walled observation lounge, originally intended to be the social center envisioned in the plans for Broadacre City.

The station’s service bays are constructed of stepped cement blocks; the staggering, as well as the mortar embedded between the rows of blocks, provides a horizontal element to the building.

Natural light enters the service area through a skylight.

Service station on display at the Pierce Arrow Museum

In 1927, Frank Lloyd Wright designed a unique and revolutionary service station for Buffalo, New York. Buffalo is the second largest city in the state after New York City, located in the area known as Western New York, and is the county seat of Erie County.

Service stations of the time typically consisted of nothing more than a pump and a small pay-as-you-go booth. Wright proposed that his designs feature a copper roof, the pumps use gravity to fill cars’ tanks, and the hoses be painted in the patriotic red, white, and blue of the United States.

It is on display at the Pierce-Arrow Museum in Buffalo, New York. Although he designed the station in 1927, it was not built until 2013. The museum is located at 263 Michigan Avenue and 201 Seneca Street, Buffalo, NY.

It had several unusual amenities, such as two fireplaces (one in the staff room) and two 13.70-meter-high totem poles.

Luxurious and clean bathrooms, a very important detail, since the women were just starting out as drivers and valued spacious and usable spaces.

When the construction of a large network of service stations was being planned, Wright demanded a commission of $1,700 at the time—more than $25,000 today—for each of his stations opened, a request that was rejected. The museum is building the station 86 years later than it was designed.

You can read the full article at https://onlybook.es/blog/wright-estacion-de-servicio-y-otras-obras-fundamentales/

Note

8

Patrick Sisson, based in Los Angeles, writes about urbanism, cities, transportation, and architecture, examining how these topics shape urban culture and life. His work has previously appeared in The Verge, Racked, Pitchfork, Dwell, and Wax Poetics.

———————–

Our blog has been read more than 1,300,000 times.

http://onlybook.es/blog/nuestro-blog-ha-superado-el-millon-de-lecturas/

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico.blogspot.com

Salvemos al Parador Ariston de su ruina

http://onlybook.es/blog/el-parador-