«This translation from Spanish (the original text) to English is not professional. I used Google Translate, so there may be linguistic errors that I ask you to overlook. I have often been asked to share my texts in English, which is why I decided to try. I appreciate your patience, and if you see anything that can be improved and would like to let me know, I would be grateful. In the meantime, with all its imperfections, here are the lines I have written». Hugo Kliczkowski Juritz

Rochester

My architectural itinerary

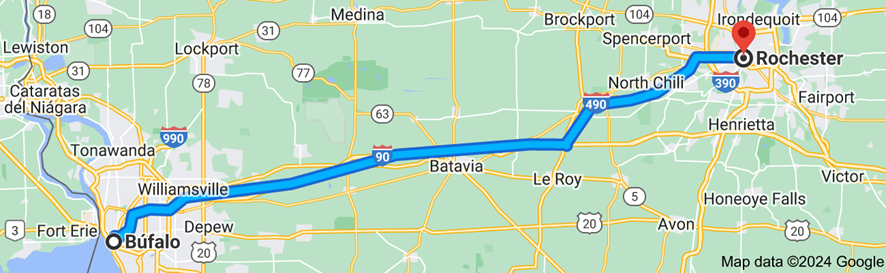

NY to Buffalo is 479 km

Buffalo to Rochester is 120 km

Rochester to Syracuse is 138 km

Syracuse to Middlebury is 264 km

Total 1.001 km

Before making my trip to Buffalo, I prepared (as I always do) my logbook, which by the way I will have to summarize, because it already has 58 pages.

Not only addresses, but also dates, times, possibility of visiting, etc. They have given me quite a few references from some pages of F.LL.Wright, with many valuable people, who know a lot and like to help.

My big question was whether from Buffalo I go to Toronto (160 km) to see Glenn Gould’s recording room, which apparently is no longer there, and his bronze figure. It seems that they have built a large auditorium, and the recording room is no longer there… (what I want to see is one of his pianos, and on an old tape recorder listen to his Goldberg Variations, which were commissioned from Bach by Count Hermann Carl von Keyserlingk (1696-1764) from Dresden, played slowly (recorded in 1981, the fast one was recorded in 1955).

If I’m not going to Toronto, I’d go to Rochester, although the Wright-designed Boyton House is undergoing renovations. What I already have is the ticket for the Darwin D. Martin house built between 1903 and 1905.

Seer https://onlybook.es/blog/wright-greycliff-la-casa-de-isabella-martin-y-su-familia-3era-parte/

In Buffalo the first thing I’ll see is the gas station at the Pierce Arrow Museum, 263 Michigan Avenue. Designed in 1928 and rebuilt in 2012, commissioned by William Heath for the corner of Cherry and Michigan

See https://onlybook.es/blog/wright-brenham-sullivan/

First Unitarian Church of Rochester

6-42 W. Main St., 20-56 Fitzhugh St., Rochester, New York

My interest in Louis Kahn comes largely from everything that Architect Miguel Angel Roca (1936) has told us about him, both in his chair at the University of Buenos Aires, where I was his adjunct professor for four years, and in countless and enriching personal conversations. I sent my thanks to Miguel from here.

Toledo en septiembre del 2024

«The sun didn’t know how great it was, until it hit the side of a building.» Louis Kahn

220 Winton Road South. Rochester.

1959 – 1969 Kahn expanded it in 1967.

On September 2, 2014, the temple was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Its exterior is characterized by deeply broken brick walls that protect the windows from direct sunlight. The complex roof of the sanctuary has light towers at each corner to let in natural light indirectly.

Paul Goldberger, architecture critic and Pulitzer Prize winner, writing in 1982 in The New York Times describing the First Unitarian Church of Rochester, “…is one of “the greatest religious structures of this century, along with the Notre Dame du Haut Chapel.” , the Unity Temple, and the First Church of Christ.”

Notre Dame du Haut. 1950/1955

Kahn y el ser-en-el-mundo

When he mentioned the school as an example of institutions that arise from inspirations, he said, “Schools began with a man who, without knowing that he was a teacher, discussed his ideas with a group of people who did not know that they were students.”

“The street is probably the first human institution, a meeting center without a roof, the school is a space where it is good to learn. The city is the place where institutions meet.”

“Everything an architect does respond first to a human institution before becoming a building.”

Thus, «architecture is based on the general forms of man’s being-in-the-world.» Martin Heidegger (1889 – 1076).

Kahn’s intention was to demonstrate that architecture is the embodiment of the incommensurable.

In this sense, it is incommensurable, although it can be measured as a building “A work is carried out between the imperious sounds of industry (creation) and when the dust settles (when the excitement of creation has passed). The pyramid of echoing silence provides the sun with its shadow.”

The affinity between Kahn’s ideas and the philosophy of the Congregation of the First Unitarian Church was one of the decisive factors in choosing him among six other architects to develop the design of their new building when urban planning regulations forced them to abandon their old one. headquarters of 1859. (1)

The congregation of the First Unitarian Church of Rochester voted in January 1959 to sell their existing building in downtown Rochester, New York, thinking they would be around until July 1961. However, construction weakened the building, forcing them to move in September of 1959.

The former First Unitarian Church building was architecturally significant, as it was designed by Richard Upjohn (1802 – 1878) a prominent 19th century architect and first president of the American Institute of Architects. The church decided to replace it with a building designed «by a prominent 20th century architect, giving the community a notable example of contemporary architecture.»

The search committee, made up of church members who had a background in architecture, decided to focus on prominent architects who had established relatively small offices and who did most of the creative work themselves.

Although Kahn’s own subsequent account of the development process suggests – misleadingly – that it was produced in a fluid and coherent manner, the truth is that the built project – of which both Kahn and the clients were to be very satisfied – was the result of no less than six different versions.

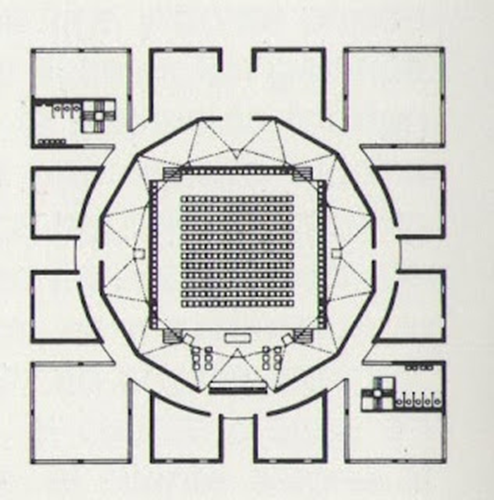

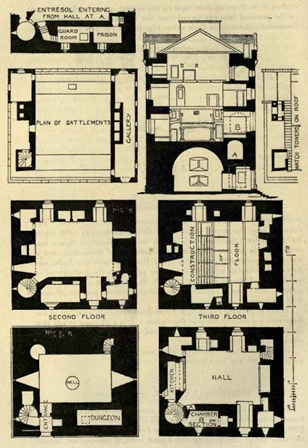

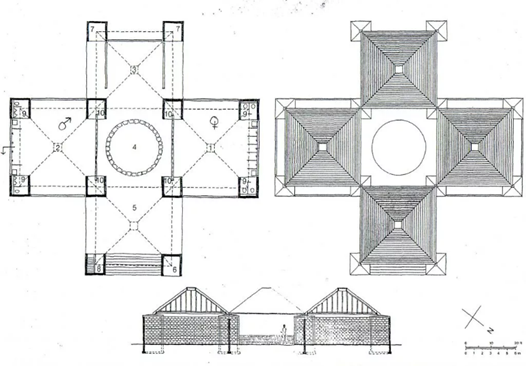

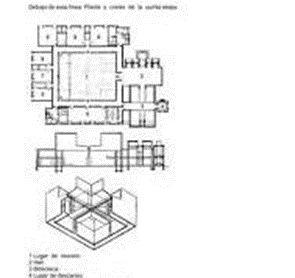

The first tests, carried out by Kahn before knowing the specific site and program, proposed a centralized type scheme, directly inspired by Renaissance churches. This is how the first design emerged, which proposed a large circular worship room enclosed within a square with four towers in the corners.

This approach clearly expressed Kahn’s idea about the composition and form appropriate to the project, but it did not adequately respond to the functional requirements and far exceeded the financial possibilities of the congregation. (2)

The different versions of this project were distorting the original idea without pleasing the clients, who from the beginning had insisted on the separation of the school and the sanctuary into two independent groups.

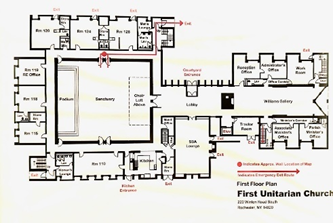

Kahn, who was resistant to this idea, was willing, however, to rethink the project from scratch and, through a new phase of versions, arrived at a solution that harmonized his clients’ ideas regarding the configuration of a Unitarian temple (to which Wright’s Unity Temple responded much better) with their own questions about the “desire” for the classrooms and premises to be smaller and arranged around the large worship hall.

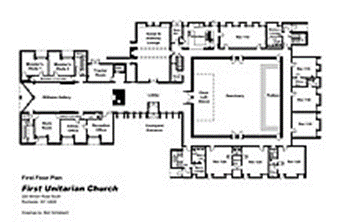

The satisfaction of the congregation is demonstrated by the fact that, in 1967, they went to Kahn to extend the building, which he resolved by means of a complementary body joined to the main one through a gallery, breaking in part with the homogeneity and the compactness of the original project.

Design process

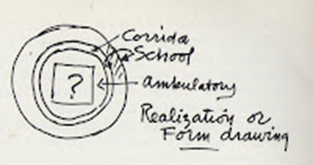

The history of the design process at the First Unitarian Church, including Kahn’s creation of what he called a form drawing, «is almost a classic in the history and theory of architecture» according to Katrine Lotz, a professor at the School. of Architecture from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.

He began by creating what he called a form drawing to represent the essence of what he intended to build.

I remember that, in my student days at the University of Buenos Aires, we called it “guiding idea, or simply party idea”, a first idea, with the strength of proposing concepts drawn without having formal or functional prejudices, that drawing, prudently angry, he guided us as we solved the project. (thanks Edgardo).

He drew a square to represent the sanctuary, and around the square he drew concentric circles to indicate an ambulatory, a corridor, and the church school.

In the center he placed a question mark to represent his understanding that, in his words, “the way the unitary activity was carried out was linked to what the Question is. «Eternal question of why anything.»

His approach was to design each building as if it were the first of its kind. August Komendant (1906 – 1992), a structural engineer who worked closely with Kahn, said that during the initial stages of design, Kahn struggled with questions of the type “How would a Unitarian Church be designed? What is unitarian religion? and studied Unitarianism in depth. The result sometimes confounded expectations. When the completed First Unitarian Church was shown at an architectural exhibition in the Soviet Union, the mayor of Leningrad commented that it did not look like a church, Kahn jokingly replied, «That’s why it was chosen for display in the Soviet Union» .

Prior to hiring Kahn, they contacted five architects.

Frank Lloyd Wright expressed little interest, and his proposed fees were high. (Wright died shortly afterward at the age of 91.)

Eero Saarinen had support from the community, but was unable to take the job due to time constraints.

The committee also met with Paul Rudolph, Walter Gropius and Carl Koch.

They spent a day with Louis Kahn in May 1959 and were impressed by his philosophical approach, the atmosphere in his office, the assurance that he would personally be in charge of the design.

Robin B. Williams, writing in Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture, “attracted his clients to the high compatibility of his philosophy with unitary ideas.”

Robert McCarter (3), one of Kahn’s biographers, points out parallels between his ideas and those in the Essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 – 1882) (4), an important figure in Unitarian history.

Kahn, who came from a non-observant Jewish background, was spiritual in a way that has been described as “pan-religious” by Carter Wiseman (5), one of his biographers.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primera_Iglesia_Unitaria_de_Rochester_%28edificio%29

“…Its architecture reflected spirituality”

FAIA (abbreviation for Fellow of the American Institute of Architects) David Rineheart (1928 – 2016), who worked for Kahn, explains: “For Lou, every building was a temple. Salk was a temple to science. Dhaka was a temple for the government. Exeter was a temple to learning.” (6)

During the Great Depression, Kahn worked with unions and civic agencies to design affordable housing. He worked as an assistant architect on the Jersey Homesteads, a project to resettle Jewish garment workers from New York City and Philadelphia into a rural kibbutz-like collective that combined agriculture and manufacturing.

During the 1948 presidential election, he worked with the third party campaign of Henry A. Wallace, who was nominated by the Progressive Party.

Kahn gave a philosophical presentation of his ideas at a congregational meeting in June 1959, after which the church commissioned him to design its new building. During that same visit he helped choose the site that would be purchased for the new building.

That year Kahn was chosen to design the Salk Institute, and in 1962 he was selected to design the Jatiyo Sangsad Bhaban in what would become the capital of the new nation of Bangladesh.

The building committee told him that the new building “must support the community at large and must express “the dignity rather than the depravity of man.”

The congregation’s broad approach to the statement of requirements was similar to Kahn’s philosophical approach to his architectural design, which he explained in «Form and Design» an article he wrote while working on this project.

Using the First Unitarian Church of Rochester as an example, he said: “In my opinion, a great building must begin with the immeasurable, it must go through measurable means when it is designed, and in the end it must be immeasurable… But what is immeasurable is the psychic spirit.”

Kahn associated the incommensurable with what he called Form, saying that “Form is not design, nor a figure, nor a dimension. It is not a material thing. Form… characterizes a good harmony of spaces for a certain human activity.»

Form, he said, was not to be understood as an architectural design. He drew a square representing the sanctuary, and around the square he placed concentric circles representing an ambulatory, a corridor, and the church school.

In the center of the square he placed a question mark which, he explained, represented his understanding that “the form of realization of the Unitarian activity was linked to what the “Question” is, the eternal Question of the why of anything.”

Kahn delivered his first design in December 1959, proposing a square building three stories high with four-story towers at each corner.

The sanctuary was a square area in the middle of a large twelve-sided room in the center of the building. The rest of the almost circular room was an ambulatory space that had to be protected from the sanctuary.

«I felt the ambulatory was necessary because the Unitarian Church is made up of people who have had previous beliefs (…) So I drew the ambulatory to respect the fact that what is said or what is felt in a sanctuary is not necessarily something in which that you have to participate. And then you could walk around and feel free to walk away from what is being said.”

Kahn had developed the idea of this type of ambulatory before his work at the First Unitarian Church, and referred to it during a talk in 1957 in the context of a university chapel.

The central hall was to be surmounted by a complex dome and surrounded by a corridor outside its walls that would provide connections to the three-story church school on the building’s periphery.

School students could watch church services “from the open spaces above.”

Prompted by complaints about the cost, which was several times the amount that had been budgeted, he quickly removed a floor from the proposed building.

The committee, however, was also unhappy with other aspects of the design, such as its rigidity and lack of usable classroom space — the irregularly shaped rooms on the periphery created by the placement of a large, almost circular room within a square building. and the possibility of children listening upstairs and people entering and leaving the sanctuary disrupting services.

In February 1960, Helen Williams, chairwoman of the building committee, wrote to him that «we are not at all happy with the present concept you have given us» and a week later she wrote: «We remain firm in the conclusion that we must have a completely new concept.«

Claiming that “Kahn has failed us miserably,” Williams resigned from the building committee.

Kahn agreed to create a new design, much to the relief of the building committee, which feared he would demand payment for work performed and walk away from the commission.

For his new design, Kahn proposed a slightly elongated rather than rigidly square building.

He resisted suggestions to place classrooms in a separate wing to reduce the possibility of rowdy children disrupting services, retaining the concept of surrounding the sanctuary with the church school. Kahn eliminated ambulatory space within the sanctuary walls, but retained the hallway just outside to provide access to the classrooms.

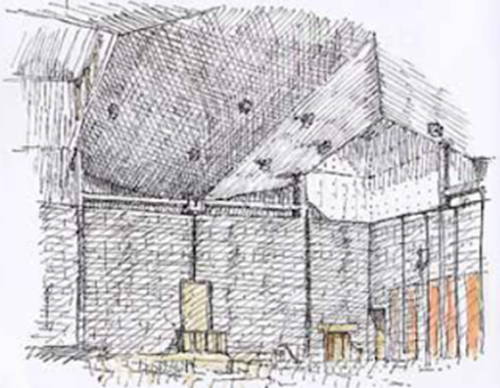

The roof over the sanctuary was one of the last aspects of the design to be completed

One option would have been to cover the sanctuary with a steel structure, but Kahn had decided in the early 1950s that he would no longer use such structures, preferring the more monumental appearance he could achieve with materials such as concrete and brick.

Not completely satisfied with the roof design he had developed, as I have already mentioned, Kahn asked his collaborator August Komendant, a pioneer in the use of prestressed concrete, for suggestions, which allowed him to create lighter and more elegant structures than normal concrete.

Komendant kept the overall design of the roof, but redesigned it as a prestressed concrete folded plate structure that would require support only at its edges, eliminating the need for the solid concrete beams that Kahn had planned to use as support for the roof structure.

Kahn initially planned to bring natural light into the sanctuary through light slits in a series of concrete caps on the roof, but the construction committee estimated that each cap would weigh 33 tons (30,000 kg), creating support problems. The light towers in Kahn’s final design are glazed only on their inner sides, a suggestion that originated in meetings with the committee.

The new design was overwhelmingly approved by the congregation in August 1960. At the dedication of the new building in December 1962, Kahn spoke about the relationship between architecture and religion.

Komendant said: “He told me that in his speech he described the cathedrals, the size and height of which were intended to show the greatness and power of God and the baseness of man, so that men would be frightened and obey His laws. For this church he used atmosphere and beauty to create respect and understanding of God’s goals, goodness and forgiveness.”

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primera_Iglesia_Unitaria_de_Rochester_%28edificio%29

The exterior of the building is characterized by deeply folded brick walls created by a series of slim, two-story light hoods that help protect the windows from direct sunlight.

The main entrance to the building is not visible to people passing by on the street.

Light towers at each of the sanctuary’s four corners rise above the exterior walls of the building, allowing the shape of the sanctuary to be easy to view from the outside.

Habitable Walls (1)

Kahn, Heidegger. The language of Architecture by Christian Norberg-Schulz

The impression Kahn created “of the sanctuary embedded within the larger building” is similar to the “box within a box” approach he used in several other buildings, notably the Phillips Exeter Academy Library.

Ver https://onlybook.es/blog/impresiones-de-un-relator-desde-el-middlebury-college/

The building echoes the design of the Scottish castles that fascinated Kahn, particularly Comlongon Castle,

Comlongon Castle has a single large room in the center surrounded by 20-foot-thick walls. Those unusually thick walls allowed entire secondary rooms to be carved from their insides, effectively turning them into inhabited walls.

In the case of the First Unitarian Church, the large central hall is the sanctuary, and the «inhabited walls» can be perceived as the two surrounding floors of rooms.

The windows in these rooms are so recessed that they are inconspicuous when viewed from an angle, and the corner spaces of the building are windowless, all of which adds to the perception that the sanctuary is surrounded by massive, sturdy walls.

In Kahn’s words, «the school became the walls surrounding the issue.» The church hired Kahn in 1964 to do an addition, which was completed in 1969.

Its exterior is relatively disjointed, in contrast to the sculpted walls of the original building.

According to scale drawings, the irregularly shaped building measures approximately 240 by 120 feet at its longest and widest points. Approximately 23 meters is from the 1969 extension. Its footprint on the land is 1,384 m².

A low ceiling

Instead of a large entrance at the front of the building that leads directly to the sanctuary, the First Unitarian Church is accessed through a side door that requires a right turn to reach the sanctuary.

The entrance is beneath the low cantilevered choir ceiling, creating a sequence from shadow to light.

“Civilization is measured by the shape of its roof,” Kahn said.

The complex roof of the sanctuary rises above the two stories of the surrounding rooms.

Light towers at the four corners bring indirect natural light to areas that are not normally well lit.

Kahn said: «If you think about it, you realize that you don’t say the same thing in a small room as you do in a big room.»

The cruciform shape Kahn used for the roof is one he had used in previous works, notably the Trenton Jewish Community Center.

The massive roof structure is supported in part by twelve slender columns embedded in the walls of the sanctuary, three columns per wall. Each central column is braced to the columns on each side by horizontal beams. The roof is lower and darker in the center, the opposite of classical church domes that are higher and brighter in the center.

The wall hangings were designed by Kahn and, like the building itself, contain no literal symbolism.

At Kahn’s request, the panels span the entire color spectrum, yet were constructed entirely from one red, one blue, and one yellow thread, with the remaining hues created from blends of those three threads. The panels were designed not only for visual effects, but also to correct a sound problem that was reverberating off the concrete walls.

The main construction materials of the interior are concrete blocks, poured concrete and wood, a combination he used in most of his later projects.

The walls of the sanctuary are 24 inches thick and constructed of concrete blocks, the hollow spaces within the walls serving as ventilation ducts.

Light and Silence

During initial design discussions, Kahn asked Komendant, “What is the most important thing in a church?” and then he himself answered that question by saying “the essence of atmosphere for a church is silence and light. Light and Silence! «

“Silence and Light” later became the name of an essay Kahn wrote in 1968 in which he explained concepts crucial to his philosophy.

Architectural historian Vincent Scully said of the church:

«You can really feel the silence of which he spoke, vibrating as with the presence of divinity, as the cinder block turns silver from the light flooding into it, while the heavy slab , rises above the head».

The editor of his writings, Robert Twombly, said that by silence, Kahn meant «each person’s desire… to create, which for Kahn was the same as being alive.»

Benches with small side windows cantilevered from the exterior walls are placed in classrooms. These spaces create the impression of small rooms carved into the exterior walls and, according to Robert McCarter, continue Kahn’s architectural theme “of the classrooms themselves appearing as rooms embedded within castle-thick walls.”

Monumentality and authenticity

Sarah Williams Goldhagen, author of Louis Kahn’s Situated Modernism, says that Kahn was concerned with the socially corrosive aspects of modern society.”

He believed that “architecture should favor the ethical training of people. “People who are anchored in their community, morally obligated, and psychologically connected to the people around them make better citizens.”

Kahn’s first major essay as sole author, published in 1944, was called Monumentality, a concept he defined as «a spiritual quality inherent in a structure that conveys a sense of its eternity.»

At the First Unitarian Church, Goldhagen says, the column-shaped light rhythms that Kahn sculpted into the façade are among the devices that increase the impression of massiveness and give the building an air of monumentality, he said: «I believe in frank architecture. A building is a struggle, not a miracle, and the architect must recognize this.«

Architecture of Institutions

According to Goldhagen, it was the first building Kahn built that gave “an indication of his mature style.”

Goldhagen says that at the First Unitarian Church, Kahn developed a philosophy for creating architecture for such organizations: «Kahn’s philosophy of the architecture of institutions, developed while designing the First Unitarian Church in Rochester, stipulated that the first and highest duty of the architect was to develop an idealized vision of the ‘way of life’ of an institution and then give shape to that vision, or as he would have put it, Form.”

Kahn made his enthusiasm for the First Unitarian Church evident even before it received final approval from the building committee.

As early as October 1960, at a conference in California, he had chosen it to illustrate a pair of terms, «form» and «design,» that were becoming key principles of his philosophy. He used these words to describe his conception of architecture, and in particular his design procedure, as the translation of the intangible into the real. It was at this time that Kahn mythologized the way the church’s design had evolved, composing an account (accompanied by the now famous diagram) that, since its publication in April 1961, has been seen as the clearest illustration of its design approach.

“Schools began with a man who, without knowing he was a teacher, discussed his ideas with a group of people who did not know they were students.”

Kahn worked on this lecture for several months and published it as an essay titled Form and Design. A colleague described it as the best embodiment of his ideas at the time and said that when people requested examples of Kahn’s publications, he most often sent this essay.

Kahn’s intention was to demonstrate that architecture is the embodiment of the incommensurable.

He used to mention the school as an example of institutions that arise from inspirations “Schools began with a man who, without knowing that he was a teacher, discussed his ideas with a group of people who did not know that they were students.”

“The street is probably the first human institution, a meeting center without a roof, the school is a space where it is good to learn. The city is the place where institutions meet.”

“Everything an architect does responds first to a human institution before becoming a building.” Thus, architecture is based on the general forms of man’s being-in-the-world. Martin Heidegger, 1889 – 1976.

In this sense, it is incommensurable, although it can be measured as a building. “A work is made between the imperious sounds of industry (creation) and. When the dust settles (when the excitement of creation has passed)(…), the pyramid of resonant silence provides the sun with its shadow.”

The 1950s constitute a decisive turning point in the career of Louis I. Kahn, a moment in which his ambition to understand the very origin of architecture led him to propose a series of decisive transformations in the conception of order and space. modern. His intuitions about the autonomous and indivisible condition of the room from the intimate commitment between envelope and structure were intertwined with a simultaneous interest in the processes of growth of the form, partly influenced by key figures of the North American context such as Buckminster Fuller (1895 – 1983). ) or Robert Le Ricolais (1894 – 1977) but above all for his intense collaboration with the architect Anne Tyng (1920 – 2011).

The evolution of the Trenton Jewish Community Center project can be considered a paradigmatic example of this crossroads of interests, naturally assuming the transition from a «cellular» plot with an organic appearance to a tartan scheme with classical connotations. The main objective of the article is to shed new light on the reason for this transition and to do so it proposes the reconstruction of the hypothetical creative process of its author, by redrawing the different versions of the project. The aim is to detect key episodes in decision-making, such as the debate established between Kahn and Colin Rowe (1920 – 1999) following the latter’s visit to Philadelphia, which could have encouraged a radical change in the proposed anatomical model. Louis I. Kahn, Anne Tyng, Colin Rowe, Trenton Jewish Community Center, modern review, growth patterns.

Kahn’s belief in “what the building wants to be,” as he often repeated in his lectures, was strongly conditioned by this Wrightian ideal.

Kahn said: “It is a happy moment when a geometry is found which tends to make spaces naturally, so that the composition geometry in the plan serves to construct, to give light and to make spaces.”

“It is a happy moment when you find a geometry that tends to make spaces naturally, so that the geometry of the plan composition serves to build, give light and make spaces.”

Richard Saul Wurman, editor “What will be has always been: the words of Louis I. Kahn” New York. Access and Rizzoli. 1990, What will be has always been: the words of Louis I. Kahn.

And those of Wright: “There is a life principle expressed in geometry at the center of every Nature-form we see. This integral pattern is abstract, lying within the object we see and that we recognize as concrete form. It is with this abstraction that the architect must find himself at home before Architecture can take place.”

“There is a principle of life expressed in geometry at the center of every form of Nature that we see. This integral pattern is abstract and is found within the object we see and recognize as a concrete form. It is with this abstraction that the architect must become comfortable before Architecture can take place”.

“Frank Lloyd Wright, Collected Writings of Frank Lloyd Wright.” New York: Rizzoli, 1992, vol. I, For the cause of architecture: composition as a method in creation, 259–60.

What does a building want to be?

A rose wants to be a rose

In the discussion of Kahn’s philosophy, his famous question: What does a building want to be? is usually taken as a starting point. This question has a greater scope than the approaches of functionalism. As a matter of principle, functionalism is circumstantial, since it starts from the particular or the general, although it may accept the concepts of typology and morphology.

Kahn’s question, on the other hand, suggests that buildings possess an essence that determines the solution. Thus, his approach represents an inversion of functionalism; the latter starts from the bottom, while Kahn starts from the top.

He emphasizes again and again that there is an order that precedes design. One of his statements begins by saying “Order exists.” This order encompasses all of nature, including human nature.

In his early writings, he used the word form to designate what a thing wants to be; However, he himself must have perceived the danger of misunderstanding, since this term usually has a more limited meaning.

That is why he introduced the term pre-form.

Then he preferred to refer to the field of essences with the word silence. Silence is immeasurable, but it contains the desire to be. Every form has a desire for existence that determines the very nature of things. This desire for existence is satisfied through design, which involves a translation of the internal order into being.

Boynton House in Rochester

The Boynton House was designed in 1908 by Frank Lloyd Wright, it is located at 16 East Blvd, in the city of Rochester, in the state of New York (14610).

No visitors allowed at this time. (August 2024).

Part of Wright’s Prarie Style repertoire of homes, this house was commissioned by Edward Everett Boynton, for him and his teenage daughter Beulah Boynton.

Some of the following photos are courtesy of the Wright Legacy Group.

The first floor has abundant windows, especially in the dining room, with skylights, a strip of skylights and a long window made up of folding modules, which join together to create different levels of lighting.

Next is the living room which features millwork with a similar window configuration on two sides and glass doors leading to a gallery at the northwest end of the home.

Wright was heavily involved in the design process and traveled to Rochester several times to oversee construction.

He also designed much of the furniture, such as the large dining room table, which has a wooden structure that holds the lamps, with a notable design.

We already anticipate the one on the dining room table in the Robie house, completed two years later.

Edward Boynton commissioned Wright to build a total work of art, including the house, landscaping, and furniture.

The site, which stretched across three city lots, gave Wright the space to incorporate a large garden, tennis court, and rectangular reflecting pool, providing the feel of an open prairie.

Boynton had sufficient resources due to his enormous success in his business selling lighting fixtures, he was a partner in CT Ham Manufacturing Co. of Rochester.

But his financial success failed to prevent Boynton’s personal life from being marked by tragedy.

Three of his four children died at a young age, including Bessie, the twin sister of his daughter Beulah.

On April 13, 1900, his wife died. Beulah told Times Union reporter William Ringle, «My father didn’t have any more hobbies than I did.»

When Boynton decided to move from his home at 44 Vick Park B in Rochester he commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design what would become the only Wright-designed home in the city.

Beulah Boynton recalled: «My father wanted the architect Claude Bragdon (8) to build our house, because he was captivated by Wright, until he was able to hire Wright.»

Edward Boynton learned of Frank Lloyd Wright through his business partner Warren McArthur, as Wright had designed the McArthur House in the Kenwood district of Chicago in 1892. It was in 1906 that Boynton commissioned Wright to design a house on a spacious property on East Boulevard.

Construction began in 1907 and was completed the following year.

His daughter Beulah Boynton was a teenager when she met Frank Lloyd Wright.

He became very interested and involved in the design and construction of houses.

«I learned to read the specifications. I discovered a mistake in the bricklayers who were placing the chimney.»

Wright, in an unusually fruitful collaboration with 21-year-old Beulah, designed the two-story house to stand sideways on the site in an elongated “T”-shaped plan.

Art glass windows and a large terrace characterize the home, which has suffered numerous structural problems due to Rochester’s harsh winter conditions.

New owners

Kim Bixler is the author of the book “Growing Up in a Frank Lloyd Wright House” and can be seen in the 2012 PBS documentary Frank Lloyd Wright’s Boynton House: The Next Hundred Years, as well as in the “Wall Street Journal,” “The Not Too Serious Architecture Hour” and on NPR’s “Here & Now” in celebration of Wright’s 150th birthday.

He graduated from Cornell University in 1991 and New York University.

His family owned the Boynton House from 1977 to 1994.

The book “Growing Up in a Frank Lloyd Wright House” chronicles the joys and pitfalls of owning a house he designed. The house’s tumultuous history is told through interviews with former and current owners. It tells what it is like to live with the curiosity of the public, play hide-and-seek, deal with the usual roof leaks and manage constant renovations.

Restoration

The Boynton House’s current owners, Jane Parker and Francis Cosentino, who purchased it in 2009, have just completed a painstaking two-year restoration project.

The process, which was completed in 2012, was documented by Rochester Public Broadcasting Station in a program titled “Frank Lloyd Wright’s Boynton House: The Next Hundred Years.”

It is the only house made by Wright in Rochester, and an example of his Prairie houses. And it is one of the few Wright houses that continues to function as a private residence, as they are generally preserved as public museums.

The restoration was carried out by a local architecture company Bero Architecture, and the landscape design was done by the company PLLC. Bayer Landscape Architecture.

Originally, in 1908 the house stood on three lots, two of which, to the south of the house, were landscaped.

Today the house is on a single urban lot.

The most striking thing about the restoration was returning the spectacular cantilevered roof, common in Wright’s projects. This was because it had been closed shortly after the completion of the house.

The restoration has received congratulations from the Landmark Society (7), its president, Mary Nicosia, and its executive director, Wayne Goodman.

The house has 235 pieces of art glass, many of which are in the dining room.

Notas

1

Living Architecture. First Unitarian Church of Rochester. Architect Louis Kahn.

2

10/03/2013. Kiara. https://proyectoskiara.blogspot.com/2013/03/iglesia-unitaria-de-louis-kahn.html

3

Robert McCarter Architect, teacher and writer, two of his books, “Louis I. Kahn” and “On and By Frank Lloyd Wright”, were finalists for the RIBA (Institute of British Architects) International Book Awards in 2006.

4

Ralph Waldo Emerson (Boston, Massachusetts, 1803 – 1882 Concord, Massachusetts) was a writer, philosopher, and poet. A leader of the Transcendentalism movement in the early 19th century, his teachings contributed to the development of the “New Thought” movement in the middle of the century.

5

Architect, professor and writer, his books include “Louis I. Kahn: Beyond Time and Style”.

A graduate of Yale College, Wiseman earned a master’s degree in architectural history from Columbia University and was a Loeb Fellow in Advanced Environmental Studies at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. From 1999 to 2010, he was president of MacDowell Colony, the nation’s oldest retreat for creative artists.

At the Yale School of Architecture, Wiseman teaches seminars on Louis Kahn, writings on architecture, and architectural criticism. He provides editorial support for education and the arts through Writertime Communications, in Weston, Connecticut.

6

Crossed dialogues between Louis I. Kahn, Anne Tyng and Colin Rowe: Guiomar Martín Domínguez. Isabel Rodríguez Martín. December 2018.

7

Landmark Society of Western New York, Inc. Created in 1937, it is one of the oldest and most active historic preservation organizations in the U.S. It is a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping communities preserve and leverage their rich heritage architectural, historical and cultural. The Landmark Society’s service area encompasses nine counties in Western New York, centered on the City of Rochester. They are Orleans, Genesee, Wyoming, Monroe, Livingston, Ontario, Wayne, Yates and Seneca.

The Landmark Society of Western New York is supported by the New York State Council on the Arts, with support from the Governor’s Office and the New York State Legislature.

8

Claude Fayette Bragdon (1866 – 1946) was an American architect, writer and set designer, who enjoyed a great national reputation with works associated with progressive architecture that were linked to Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright.

In numerous essays and books, Bragdon argued that only an “organic, nature-based architecture could foster a democratic community in an industrial capitalist society.”

Continue at https://onlybook.es/blog/wright-casa-davidson-y-midway-park-6ta-parte/

——————-

Our Blog has obtained more than 1,200,000 readings.

http://onlybook.es/blog/nuestro-blog-ha-superado-el-millon-de-lecturas/

——————–

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico.blogspot.com

Salvemos al Parador Ariston de su ruina

http://onlybook.es/blog/el-parador-ariston-

hugoklico

Architect. Argentine/Spanish. editor. illustrated book distributor. View all posts by hugoklico. Ver todas las entradas de hugoklico