22 December, 2024 hugoklico Leave a comment Edit

«This translation from Spanish (the original text) to English is not professional. I used Google Translate, so there may be linguistic errors, which I ask you to overlook. I have often been asked to share my texts in English, so I decided to make an attempt. I appreciate your patience, and if you see anything that can be improved and would like to let me know, I would be grateful. Here are the lines I have written in the meantime, with all their imperfections». Hugo Kliczkowski Juritz

Was William Le Baron Jenney’s HIB (Home Insurance Building) the first skyscraper?

It comes from https://onlybook.es/blog/el-edificio-flatiron-de-nueva-york-2a-parte/

The Le Baron Jenney Myth: “How the Home Insurance Building falsely became the first skyscraper.” By Jason M. Barr, July 1, 2024. (6)

Historian and professor Leonardo Benevolo (Orta San Giulio 1923 – 2017 Cellatica) in his famous and referential book “History of Modern Architecture” on pp 245 states “1879 year Jenney builds the first tall building with metal structure”.

In the following text I mention several architects, they are William Le Baron Jenney (1832 – 1907), Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, Dankmar Adler (1844 – 1900) -Adler & Sullivan-, George B. Post (1837 – 1913), Daniel H. Burnham (1846 – 1912) -Burnham & Root-, LeRoy S. Buffington (1847 – 1931), Bradford Gilbert (1853 – 1911), Henry Hobson Richardson (1838 – 1886), John Root (1850 – 1891), Charles B. Atwood (1849 – 1895), S. E. Loring, Holabird & Roche.

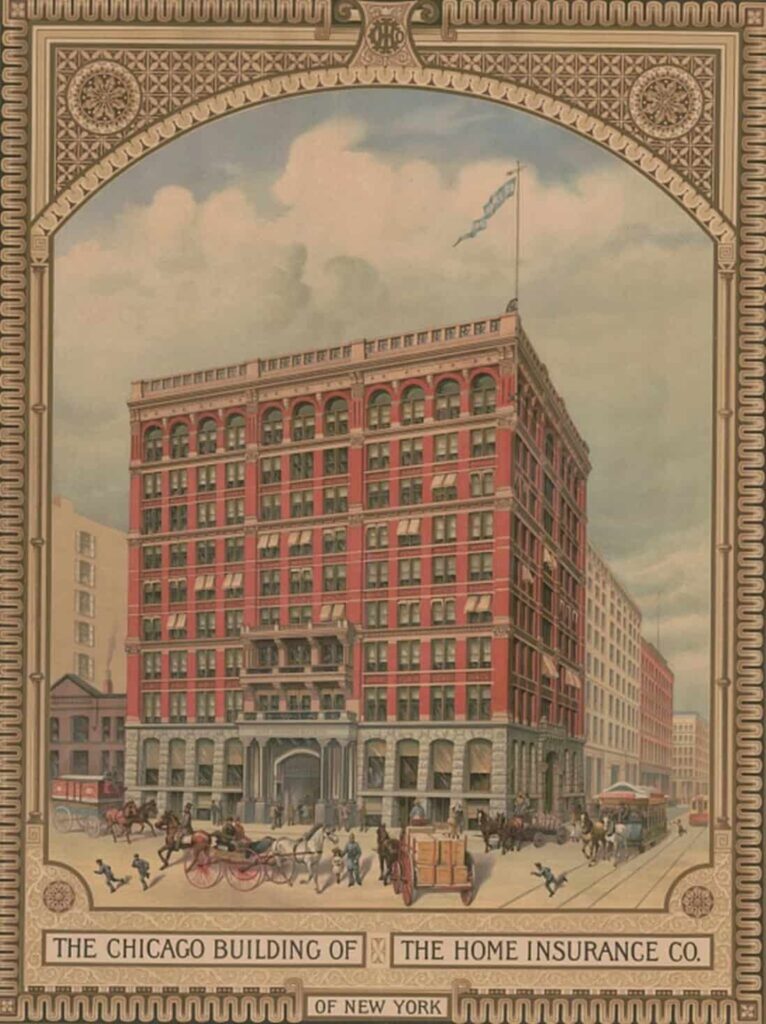

It is not easy to know if the first skyscraper was the Home Insurance Building (HIB) built in Chicago, in 1884/85, by architect William Le Baron Jenney, an engineer trained at the Ecole Polytechnique de Paris, Major of the Corps of Engineers during the Civil War, who opened his studio in Chicago in 1868.

The historian and professor Leonardo Benevolo (Orta San Giulio 1923 – 2017 Cellatica) in his famous and referential book “History of Modern Architecture” on pp 245 states “1879 year in which Jenney builds the first tall building with metal structure”.

It is not easy to know if the first skyscraper was the Home Insurance Building (HIB) built in Chicago, in 1884/85, by Architect William Le Baron Jenney, an engineer trained at the Ecole Polytechnique de Paris, Major of the Corps of Engineers during the Civil War, who opened his studio in Chicago in 1868 with S. E. Loring, in 1869 published a book of plates “Principles and practice of Architecture”, and taught architecture at the Univ. of Michigan from 1876 to 1880.

It can be said that he was an innovator in the use of structural steel.

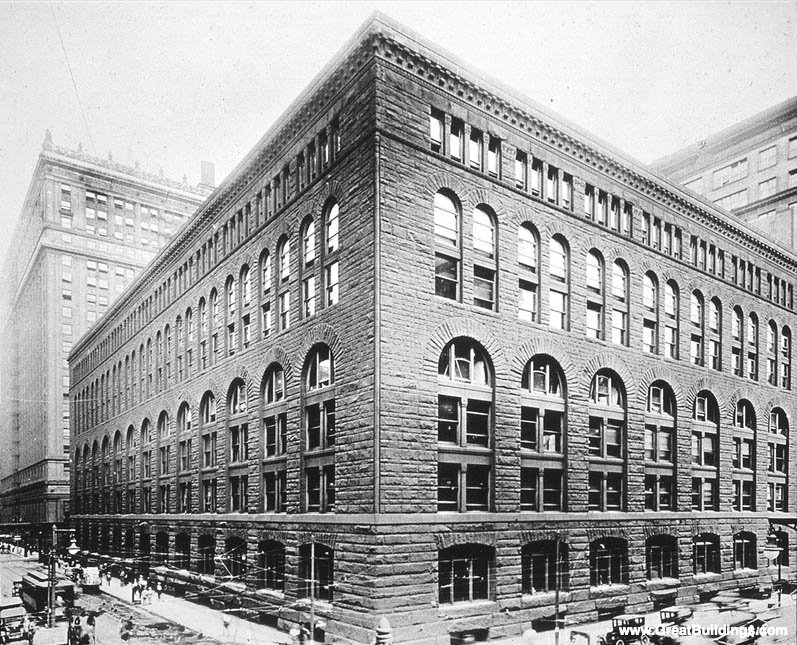

It is said of the HIB that “it was the first building with an all-metal structure and is therefore considered the first skyscraper”. In 1931 it was demolished to build the La Salle Bank Building (later the Bank of America) designed in 1934 by architects Graham, Anderson, Probst & White.

Jason M. Barr, professor of economics at Rutgers-Newark University and expert on the economics of skyscrapers writes in his book “Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers”… “The designation of Le Baron Jenney as the ‘inventor of the skyscraper’ was, rather, the result of a public relations campaign initiated by him and his fellow C

Its building did not use structural steel and was not the first all-metal building, although the HIB included some engineering innovations and its author Le Baron Jenney was one of the leading architect-engineers of his time.

In 1882 the New York Sun mentioned as a skyscraper (tall building) the Mutual Life Insurance Building of 1884 with 11 stories.

In 1883 the Chicago Tribune reported in its “New York Gossip” column about its own offices in the 10-story 1875 Tribune Building and the 10-story 1875 Western Union Building.

To define a skyscraper, in addition to its height, its structural design is important, based on three elements:

-a steel skeleton, where all beams and columns, both for external and internal use, are riveted together forming a complete lattice.

- the skeleton contains additional steel to brace the building against wind.

-the façade is a mere “curtain” that has no structural purpose.

“According to these concepts the Home Insurance Building in Chicago does not meet any of them to be considered a skyscraper, even though it is a hybrid building, combining traditional construction with steel beams.”

Le Baron Jenney in December 1885 wrote about his building in the magazine The Sanitary Engineer “his pride in having achieved a foundation design that avoided uneven settlement, […] I have implanted iron columns in the load-bearing pillars connecting them to the iron beams and to the lintels over the window and door openings”.

It should be remembered that in 1873 F. Baumann proposed new stone foundation systems, which were gradually perfected until the concrete “Chicago Caisson” was used for the first time in 1894. The steam safety elevator, first installed by E. G. Otis (Elisha Graves Otis Halifax 1811 – 1861 New York) in New York in 1857, arrives in Chicago in 1864; in 1870 C.W. Baldwin, a company worker in the Chicago Caisson, is used for the first time. Baldwin, a worker of the Otis company invents and builds in Chicago the first hydraulic elevator, while in 1887 begins to spread the use of the electric elevator, with telephone and pneumatic mail that allow buildings of any size and number of floors, facilitating the birth of the skyscraper.

An 1895 observer writes “The construction of office buildings of enormous height, with iron and steel skeleton structure supporting the inner and outer walls, has become a custom in almost every large American city. This style of construction has been born in Chicago, at least in its practical application, and this city now has more buildings of the steel skeleton type than all other American cities combined.” (7)

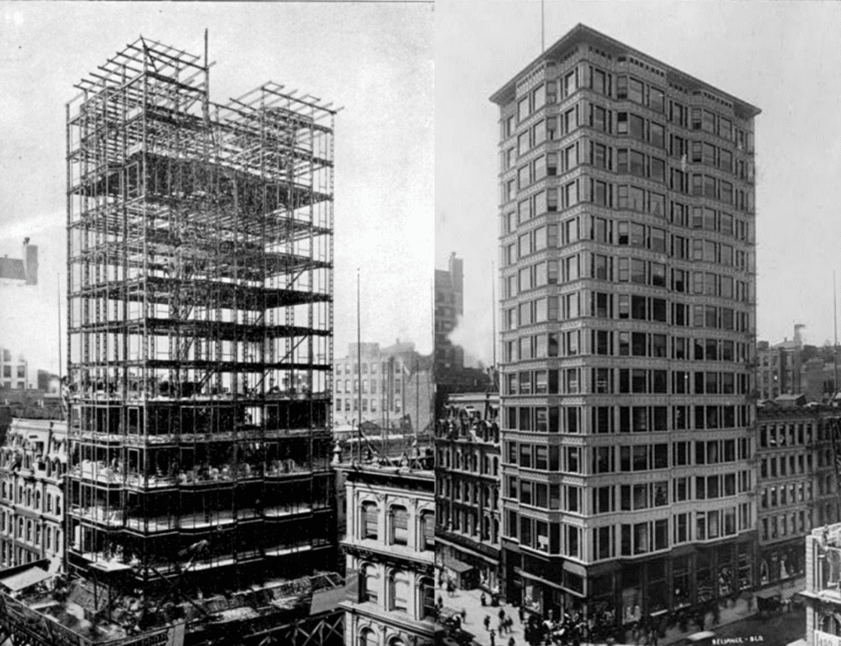

The Reliance Building (the most beautiful building in Chicago according to Benevolo) at 1 W. Washington Street in Chicago’s Loop. The basement and second floors were designed by John Root of the firm Burnham and Root in 1890.

Upon Root’s death, Burnham and engineer E.C. Shankland added another ten stories, repeating without variation the same architectural motif. The complex was not designed as a unit, but is the result of an operation of “repetition”, the motif of the continuous windows and decorated bands is repeated unaltered thirteen times, on the plinth of the first two floors.

It was the first skyscraper with large glass windows making up most of the facade, foreshadowing a feature that would become dominant in the 20th century. The Reliance Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970; and on January 7, 1976, it was designated a National Historic Landmark.

In the following years, as other hybrid and experimental buildings came on the scene such as Holabird & Roche’s Rookery (1888) and 12-story Tacoma (1889) in Chicago and the Tower Building (1889) in New York, neither copied Le Baron Jenney’s methods, their structures were inspired by iron-framed designs.

The public relations campaign

Beginning in 1896, discussion of the Home Insurance Building began to take on a very different tone. Le Baron Jenney and his colleagues claimed that the HIB was a revolutionary building.

By the 1890s, skyscrapers of 20 stories or more were going up all over the country, such as Burnham & Root’s 22-story, 200-foot-tall Masonic Temple Building (1893) in Chicago and the 20-story Manhattan Life Insurance Building (1894) in New York City.

The question was who “invented the skyscraper”?

F. T. Gates, president of a ship manufacturing company (Bessemer Steamship) in June 1896 wrote in The Engineering Record (ER) asking who had discovered the idea of steel construction in tall buildings?

Subsequently an editorial said that some early examples of tall office buildings were the Home Insurance Building (HIB), the Rookery and the Drexel Building (1889) in Philadelphia, without deciding which was the first skyscraper.

When Le Baron Jenney read Gates’ letter, he replied “My claim is that in 1883 I invented and put into practice in the Chicago building what is now known as Skeleton Construction, it was a radical departure from anything hitherto existing…” Gates replied “Your letters seem to be conclusive as to the invention of Steel Skeleton Construction.”

The claim that skeleton construction was exclusively his invention ignores the long history of the iron structure going back at least a century before HIB was conceived, not to mention the myriad other necessities to make a skyscraper possible, such as electric elevators with safety brakes and fire protection, with which Le Baron Jenney had nothing to do.

The article merited some letters of support and some not, such as one from Dankmar Adler of Adler & Sullivan in Chicago “On the whole, skeleton construction, or its current successor, steel cage construction, was a growth rather than an invention…therefore, credit therefore must be given to my profession as a whole rather than to any one in its ranks.”

Another letter was from George Post, who stated that his Commodities Exchange Building (1884) in New York should be considered the first example of curtain wall construction in a tall office building, and who is now believed by many architectural historians to have been the first to use true external iron framing.

A letter from Daniel Burnham, arguably Chicago’s most famous and important architect from the 1880s to the early 1910s, wrote: “This principle of carrying the entire structure upon a carefully balanced and braced metal frame, protected from fire, is precisely what Mr. William Le Baron Jenney worked out […] he deserves all the credit due to the engineering feat of being the first to accomplish.” The comment that he “deserved all the credit” exaggerates Le Baron Jenney’s role within this story. Burnham had worked in Le Baron Jenney’s office as a draftsman in 1868, and they were long-time colleagues and friends. His letter can be considered “more of a letter of recommendation than an impartial account.”

Barr recalls in his book that Le Baron Jenney’s building was not a “braced metal frame, as it had no wind bracing and the ironwork was not entirely self-supporting.”

Reproduction of an office building by Leroy Buffington based on his 1888 patent for iron framing. The “Cloud Scraper” was not built. Inland Architect, July 1888

The Engineering Record (ER), published a letter from Leroy Buffington, a Minnesota architect who in 1888 received a patent for iron frame construction. He stated, “I have used constructions such as the Chicago Building of the Home Insurance Company since 1876.”

Barr comments that “There is no evidence that his Minnesota buildings used external iron framing or had curtain walls.”

When Le Baron Jenney died, he continued to receive the honor in his obituaries. The Pittsburgh Press, for example, wrote: “William Le Baron Jenney, inventor of the skyscraper… died in Los Angeles, California, yesterday…” A few days later, the Chicago Sunday Tribune reported that Le Baron Jenney “discovered skeleton construction…”

Campaña por el reconocimiento

In 1896, a decade after the completion of the Home Insurance Building (HIB), William Le Baron Jenney and his Chicago colleagues, including world-renowned architect and planner Daniel H. Burnham, embarked on a public relations campaign in the trade journal The Engineering Record to convince the world that, as Le Baron Jenney claimed, “the construction of the skeleton was a radical departure from anything that had hitherto appeared and was exclusively my invention.”

Between 1885 and 1896, other architects and cities were vying for the title of “first skyscraper,” and the Chicago community was struggling to claim what it believed was rightfully theirs. As a result, they began to change the historical narrative and offer misleading statements about the structure of the Home Insurance Building.

Projects

In my search for the architect who had “discovered” the way to build a skyscraper with steel frames, and after seeing Daniel Burnham’s work with the Flatiron, I came across architect Bradford Gilbert, who did very interesting works, a large number of railway stations and accessory works such as offices and terminals not only in the USA but also in Mexico. Here are some:

1870.The White House Station

The White House Station serves New Jersey Transit’s Raritan Valley Line.

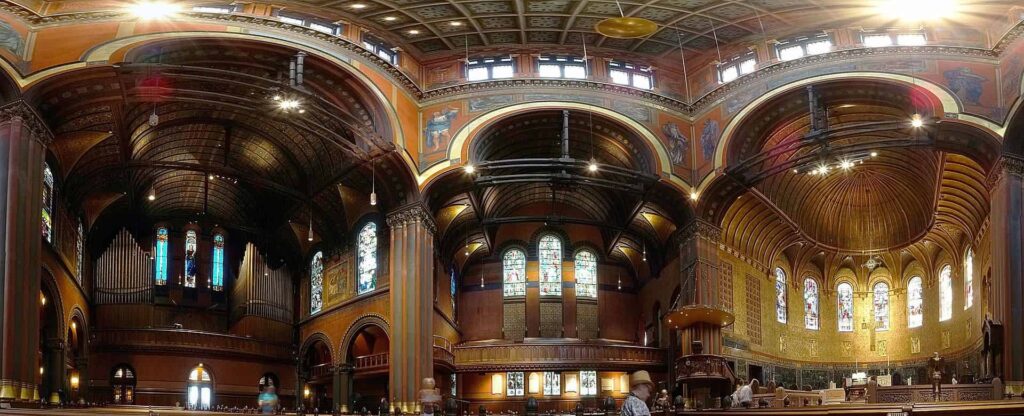

The station is on the west side of Main Street in downtown and the station building has been converted into a branch library for the Hunterdon County Library System. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984 for its architectural significance. Its style is Richardsonian Romanesque, a style of historicist architecture that developed in the United States in the late 19th century and named after American architect Henry Hobson Richardson (Priestly Plantation 1838 – 1886 Brookline). Richardson studied in Paris between 1860 and 1865 and worked mainly in Boston, for the more cultured and up-to-date American society. He belonged to a generation that, after the Civil War, brought to America a first-hand knowledge of European artistic culture (such as R.M. Hunt and C. F. McKim).

His works had a significant impact in Boston, Pittsburgh, Albany, and Chicago, among other cities. His most notable works include his masterpiece Trinity Church, Boston (1872–1877), listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the Thomas Crane Public Library in Quincy.

Richardson had found in France, in the neo-Romanesque movement of Léon Vaudoyer (1803 – 1872) (8) a language adaptable to the Massachusetts construction tradition.

Solid walls of unpolished stone (not polished with sand or other harder materials)

«It was very cold, and when I entered the Trinity Church in the autumn of 2023, I took shelter from the cold wind and made myself comfortable. They were rehearsing the organ, and I was so intoxicated that I left my beautiful woollen hat at my side, and there it remained, in the second row on the right. If anyone saw it, please let me know.»

Wholesale Store influenced the façade design of its fellow buildings.

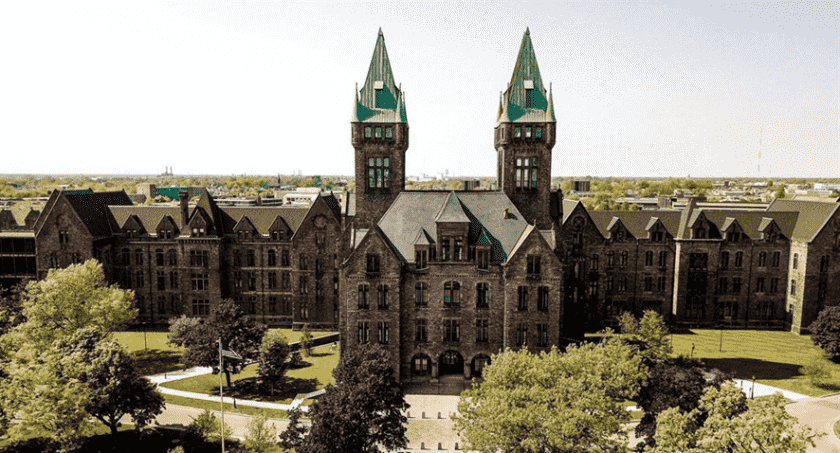

Richardson first used design elements discovered at the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane in upstate New York, designed in 1870.

In 2024 I toured the impressive (in beauty and volume) Richardson Olastead complex, inspired by medieval architecture, with the influence of William Morris and John Ruskin. Today the Richardson Grand Hotel operates there.

See https://onlybook.es/blog/gb-wright-richardson-burnham-root-sullivan-adler-koolhaas-1st-part/

1881/1894. Mason Stables, Dakota Garage. NY

Edmund Coffin Jr., a prominent real estate investor and attorney, hired Gilbert to design the Mason Stables. They were built between 1881 and 1893, and when completed, they were one of the largest livery stables in New York City. They had five stories, including 158 stalls and room for over 300 carriages.

The building, primarily Romanesque Revival in style, was decorated with some Celtic-style ornamentation, repeating patterns in orange-yellow and variegated orange-red brick, and rows of repeating thin windows. «The stables were almost abstract, a field of dreams in orange, red, and yellow masonry.» They had three entrances off 76th, 77th, and Amsterdam Streets. In 1912, the stables were remodeled into a parking lot, the Dakota Stables, and in 1950 it was renamed the Garage Pyramid. It was partially demolished in 2007 and completely demolished in 2011.

1884. YMCA Youth Institute Building. The Bowery, Manhattan

The building was located between 5th and 6th Avenues on the north side of 125th Street.

Many prestigious institutional buildings from this era survive today in the Bowery and reflect this German presence.

Gilbert designed a Queen Anne style building (usually reserved for residential architecture) for the YMCA in the Bowery, known locally as The Bunker. This was the first YMCA in New York City, originally called the Young Men’s Institute.

It was built to provide young people with housing and physical and social enrichment as an alternative to the overcrowded hostels that dominated the Bowery. It was converted into residences in 1932 with lofts and residential spaces later inhabited by many world-renowned artists.

It was brownstone on the lower levels and brick and terra cotta on the upper levels, with stepped gables in Dutch Renaissance style at the 125th Street entrance. The $65,000 ($2,204,222 today) building included a gymnasium, a swimming pool, a bowling alley, five classrooms, a library, a lounge, a reception room, a reading room, and an auditorium that could seat 800.

In June 1886, Gilbert completed another building for the YMCA in Harlem.

1884. Benjamin Ames Kimball Residence. Now Capital Theatre, Concord, New Hampshire.

1885. Concord Station, New Hampshire. Destroyed in 1959

Concord and Montreal Railway, railway depot and office building.

1887. Flatiron Building of Atlanta, Georgia

Anglo-American loan and trust company

Atlanta’s Flatiron Building (also known as the English-American Building or Georgia Savings Bank), completed in 1897, is the oldest skyscraper in Atlanta still standing. The building was designed by Bradford Lee Gilbert, who also designed the “Tower Building,” which is referred to as New York City’s first skyscraper, in 1889.

In 2016, real estate firm Lucror Resources completed a $13 million renovation, and the building will continue to be used as an office building with retail and restaurant space on the ground floor. Heritage helped Lucror Resources secure federal and state historic tax credits for the project.

Notes

6

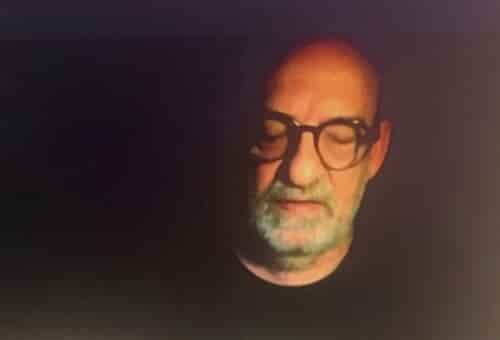

Jason M. Barr is a professor of economics at Rutgers University–Newark and an affiliate member of the Rutgers Global Urban Systems (GUS) doctoral program. He is one of the world’s foremost experts on the economics of skyscrapers. Dr. Barr received a BA from Cornell University (1992), an MA in Creative Writing from Emerson College (1995), and a PhD in Economics from Columbia University (2002). He serves on the editorial boards of the Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics and the Eastern Economic Journal. And for eleven years he served on the board of directors of the Journal of Economic Interaction and Coordination.

He has taught in Changchun, China, and conducted research at the Observatoire Français des Conjonctures Économiques. Received grants from the Land Economic Foundation, the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, and the WCF/National Park Service.

Author of Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers (OUP, 2016) and Cities in the Sky: The Quest to Build the World’s Tallest Skyscrapers (Scribner, 2014). His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Economist, The New York Times, Curbed.com, Architectural Record, StarTrek.com, Dezeen.com, Scientific American, and the Irish Independent. He currently writes the Skynomics Blog, a blog about skyscrapers, cities, and economics.

7

In the Engineering News of 1895. F.A. Randall. Page 11.

8

Léon Vaudoyer (Paris 1803 – 1872) was the son of the architect Antoine Vaudoyer. Together with his contemporaries Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste and Louis Duc, he became a leading figure in architectural circles in the 1830s.

He won the Grand Prix de Rome in 1826. In 1838 he won the design competition for the Hôtel d’Ville in Avignon (unrealised), and from 1845 (with Gabriel-Auguste Ancelet) he extended the buildings of the Priory of Saint-Martin-des-Champs (now the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts). In 1852 he was given responsibility for rebuilding the Sorbonne (not completed) and also for designing the polychrome Cathedrale Sainte-Marie-Majeure in Marseille.

——————————————–

Our blog has been read more than 1,300,000 times.

http://onlybook.es/blog/nuestro-blog-ha-superado-el-millon-de-lecturas/

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico.blogspot.com

Salvemos al Parador Ariston de su ruina

Let’s save the Parador Ariston from its ruin

http://onlybook.es/blog/el-parador-ariston-una-ruina-moderna-por-hugo-a-kliczkowski/

Post navigation

Entrada anteriorGB. The Flatiron Building in New York. 2nd part