See previous http://onlybook.es/blog/las-obras-de-frank-lloyd-wright-parte-13-su-influencia-e-influenciados-en-sudamerica/

«This translation from Spanish (the original text) to English is not professional. I used Google Translate, so there may be linguistic errors that I ask you to overlook. I have often been asked to share my texts in English, which is why I decided to try. I appreciate your patience, and if you see anything that can be improved and would like to let me know, I would be grateful. In the meantime, with all its imperfections, here are the lines I have written». Hugo Kliczkowski Juritz

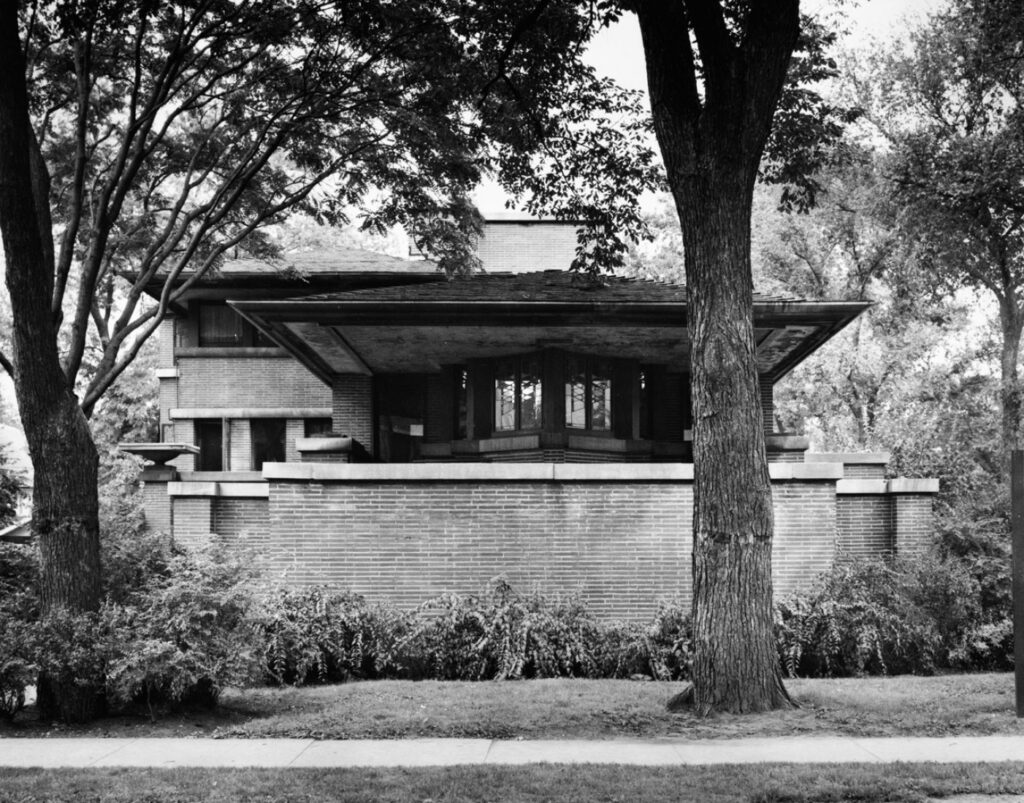

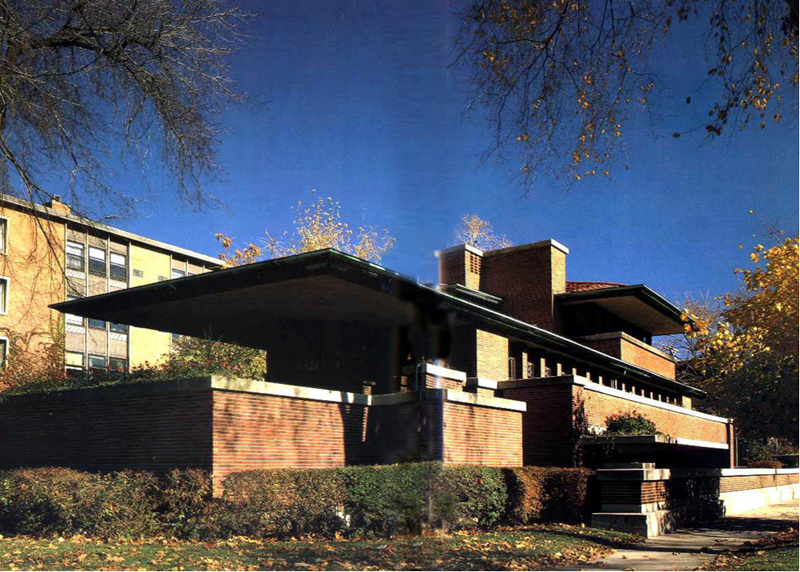

The Robie House is fundamental to understanding the history of modern architecture

“I do not intend to become the best architect that has ever existed. I intend to be the greatest architect that ever exists.” F. Ll. Wright

“What always happens is what you really believe in; and believing in something makes it happen.” F. Ll. Wright

Philip Johnson (Cleveland 1906 – 2005 New Canaan) called Wright the «greatest architect of the 19th century».

The impact of the design was so great in its time that in 1958 «House and Home» magazine chose it as the best home of the 20th century.

Beginning of the 20th century, Fred C. Robie tests a prototype of an automobile in Chicago.

His grandfather, whose last name was Räbe, was a german emigrant, and his father, who had settled in Chicago after the great fire of 1871, had started the Excelsior Supply Company to distribute sewing machine supplies.

He had begun to sell bicycles, and his dream was to manufacture motorcycles and also cars. He began studying mechanical engineering, but did not finish his degree.

With a loan from his father and at the age of 28 he set out on an industrial adventure.

He is married, has a son, and lives in rooms at the Windermere West Hotel in Hyde Park, a neighborhood south of downtown, near the university. The desire to have a house arose, and the opportunity arose. Some friends, to prevent a store from being built next to their house, bought the plot next door and sold it to the Robies for $13,500 on May 19, 1908.

There are several colleges in the neighborhood.

His wife, Lora Hiereronymus (Pekin, Illinois 1878 – 1947 Springfield) is happy although she misses her college days at Foster Hall, located a few blocks away. She graduated and taught in Springfield, the state capital. He was probably the one who suggested Wright, since Springfield was home to the Dana House (by Susan Lawrence Dana) and he knew of her work that had been published in “House Beautiful” magazine.

The investment reaches $58,500, 1,500 less than they had initially planned to spend. The plot 13,600 to which are added the 35,000 for the project and the execution and 10,000 for the furniture. Updating the figure to 2021 would be about $918,200 dollars.

The builder was H.B.Barbard Co, who began work on April 15, 1909. The Robie family moved in in May 1910, the furniture and other minor items were completed in January 1911.

Five decades later, in a conversation with a journalist, Robie would say that they recommended him for his desire for a modern home:

– I know what you want, one of those damned houses, one of those Wright ones…

With the arrival of horizontal roofs, overhanging eaves, continuous windows and natural materials, a period begins in which we say goodbye to the «neo-gothic», the «neo-colonial» and the rest of the «neos».

The story is very short and sad for Fred, in 1911 his father died, leaving behind a huge debt, to face it, he sold the house, and a year later he got divorced. (1)

Fred C. Robie in his later years stated about the Robie House:

«I think the house is ideal, it is the most ideal place in the world.»

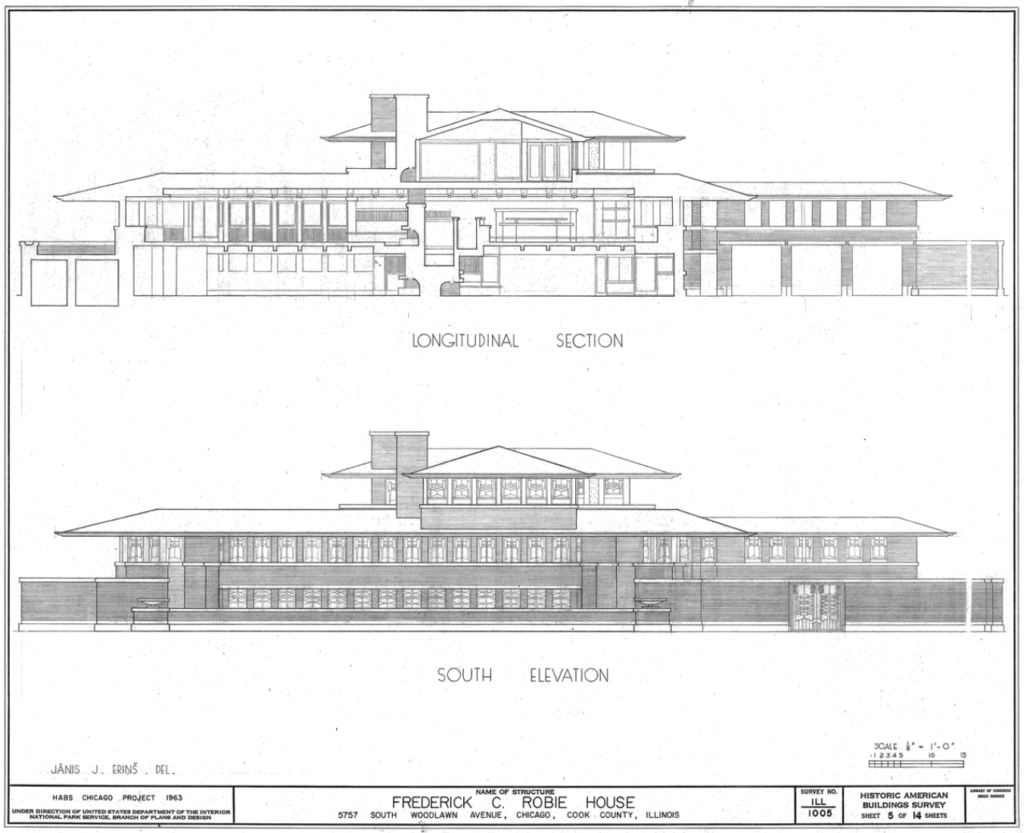

But let’s go back a few months, not many, to 1909, the project is ready and shows how Wright breaks with the traditional succession of rooms. A large room divided by a fireplace marks the birth of the open plan, it proposes many built-in furniture.

The house is resolved into 3 levels made of limestone, brick and wood, the steel is not visible.

The construction begins in 1909, in the middle of the work, Wright scandalizes Chicago by abandoning his family and escaping with the wife of a client, the work is finished by a collaborator of the Hermann V. von Holst studio (Freiburg 1874 – 1955) (2)

In 1910 the Robie family moved into the house.

The last and best of Wright’s prairie houses, the Robie House, seems designed for a plain rather than the narrow corner lot on which it sits in Hyde Park, a suburb of Chicago.

University of Chicago, 5757 Woodlawn Avenue

In the 1900s, Wright developed what would be described as his great first stage, which was characterized by the use of his own architectural language, based mainly on the use of horizontal lines and plants created around the figure of the fireplace.

According to Wright, this horizontality embodied American values, formally bringing the Midwestern prairie into its buildings. This is reflected in the publication of the “Wasmuth Portfolio” in 1910 in Berlin, where Wright attempted to show a style that “manifested and identified the ideals of democracy and the identity of the American people.” Other architect-historians such as Pevner and Giedion preferred to interpret similar ideas in a different key: a machinist conception of modernity; ideals of a new society in search of a conception of architecture. (3)

“We live on the prairie. The meadow has a very characteristic beauty. We must recognize and accentuate this natural beauty, its tranquil expanse. Hence the gently sloping roofs, the small proportions, the peaceful silhouettes, the massive chimneys, the protective overhangs, the low terraces and the advanced walls that limit small gardens.” Frank Lloyd Wright

Without a doubt, its horizontal shape must have seemed at least extravagant to the neighbors. (4)

The engineer, Frederick C. Robie, wanted a house that could be protected from fires, without closed rooms. On the contrary, he wanted an integration of all the spaces in the house. Wright would have greatly influenced that desire.

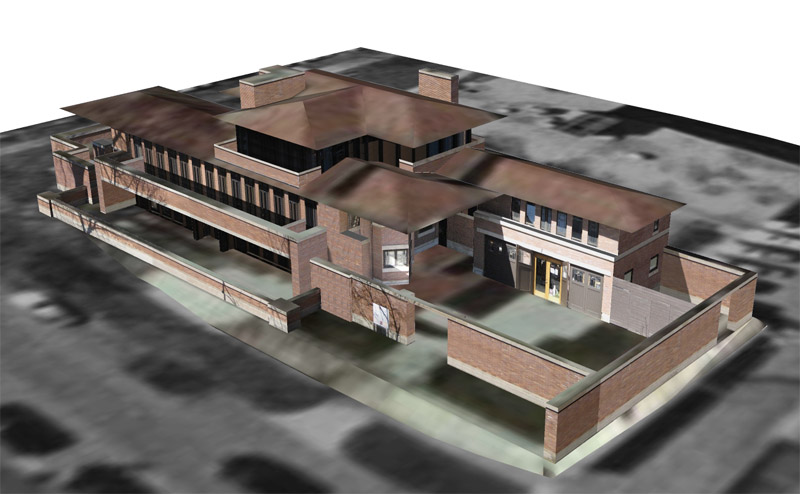

The location at an angle of the land largely explains its shape, very similar to that of other “Prairie Houses”.

Its shape is similar to that of other Prairie Houses, located at an angle of the land.

It has no clear facades, no exterior walls or traditional windows, nor a main entrance.

It occupies practically the entire plot, the little free space that is left was designed with walls and built-in planters.

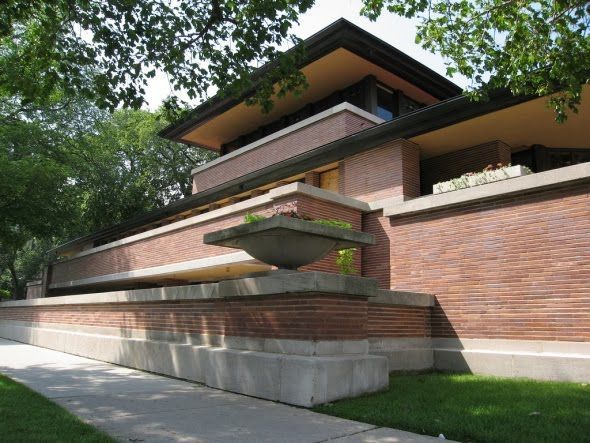

A work of horizontal features reinforced by the sills, the window lintels, and the thin bricks with recessed joints.

Wright’s design responded to the compositional method of that time, which consisted of organizing symmetrical shapes and grouping them asymmetrically.

The genesis of the design is an elongated two-story block, which, without being so, appears to be symmetrical. On the south façade, on the first floor, there is a continuous series of carpentry windows that open onto a cantilevered balcony (here the neighbors who saw a ship would be right), which provide shade over similar windows on the ground floor.

A low-slope roof, and enormous overhangs at its ends.

Beyond, at the eastern end of the building, another sloping roof covers the wing dedicated to a garage for 3 cars and the service staff, Frederick Robie, proposed a modern program, he did not want added decoration (like the Victorian houses of the time) , and wanted a playroom for his children.

The land is 842.90 m² and is narrow, so Wright chose a single axiality for the project. The house unfolds into two bodies displaced from each other, thus leaving two large gaps in the site.

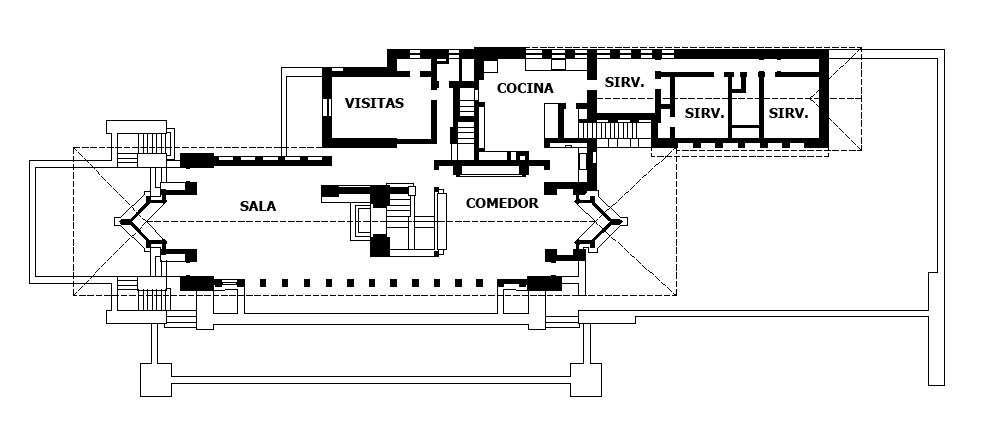

The composition of the floor plan is based on two adjacent bars that blend into a central volume, the chimney, around which the rooms connect.

The house is organized into two wings, keeping the public area facing the street and the service area in the innermost part (3).

Wright had been working on the idea of dematerializing the box, he did not want to propose closed and isolated spaces from each other.

http://onlybook.es/blog/las-obras-de-frank-lloyd-wright-parte-10-wright-pensaba-en-3-dimensiones/

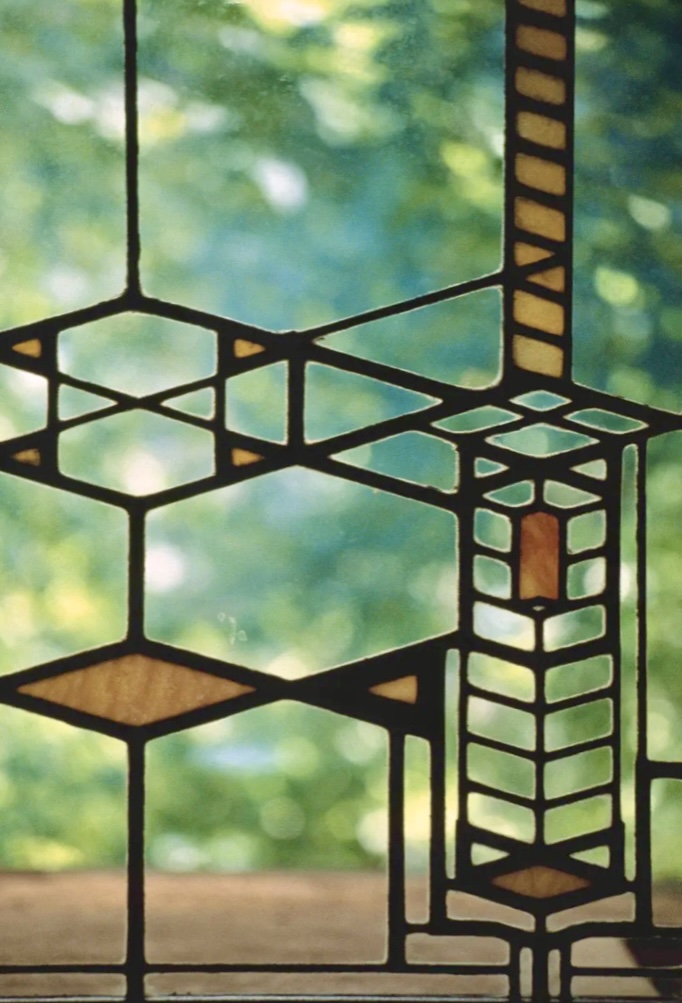

Design spaces in which each room opened to the others, obtaining visual transparency, with more light and a feeling of spaciousness. He used light material closures and ceilings of different heights, designing by differentiating between “defined spaces” and “separate spaces.”

Wright breaks with the idea of the house as a box containing rooms, which in turn are other isolated boxes.

The space achieved is fluid and transparent. It is the “explosion of the box”, which allows the play of volumes entering and exiting throughout the land.

The volumetry is made up of large terraces and eaves to give a solid and forceful image that is at the same time hollow and light (5). Wright will use this set of terraces and eaves in the Casa de la Cascada.

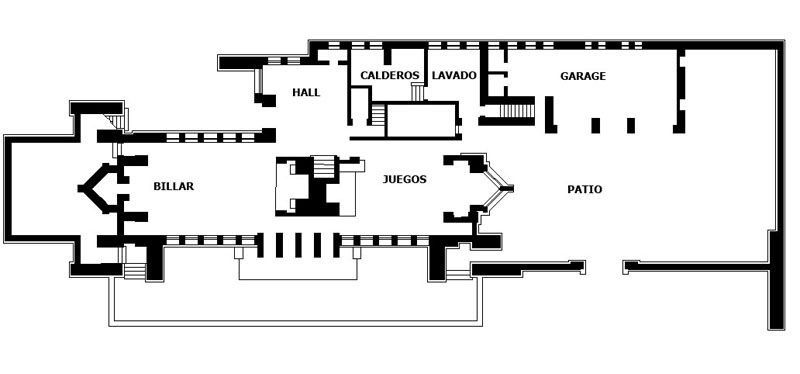

Ground floor

The access, which through stairs leads to the main floor.

Games and billiards room, and the public area of the house. All of them separated by the chimney.

In the basement at street level there is the boiler and heating machines, laundry room, pantry, cellar and garage for 3 cars. (6)

First level

It is accessed by the central staircase.

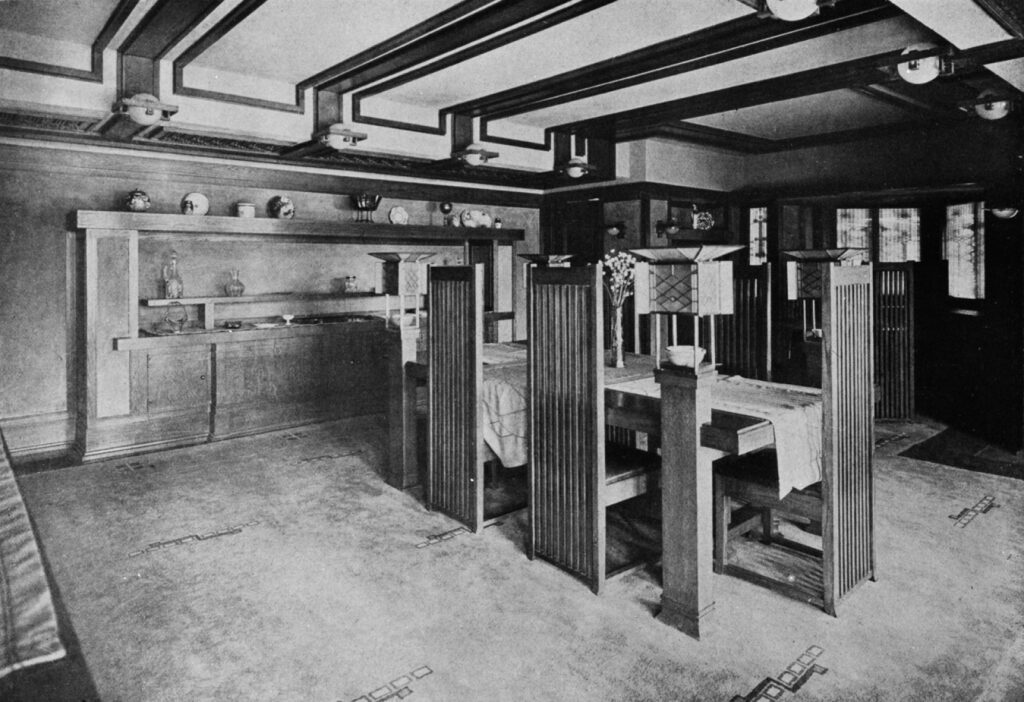

Living room and dining room are separated by the fireplace but visually linked.

It is a large, long, low room, very illuminated. There are no walls that could hinder the view to the outside and the entry of light, although the eaves allow privacy to be maintained. On the same floor there is a guest room, the service wing with the kitchen and the service staff’s rooms.

Chimney

It has an important presence in the environment, it is possible to go around it and continuity is perceived through a rectangular opening in its upper part.

Ceiling

It is divided into panels, with different types of lighting, glass globes on each side of the central, higher area and light bulbs hidden behind the wooden gratings in the lower, lateral areas.

At the ends there are triangular spaces, more intimate areas for living and even eating.

The shadow cast by the wide eaves keeps them “hidden”, but at the same time reinforcing the idea that the space extends to the outside.

The covers are supported by two hidden steel beams that run throughout the main block.

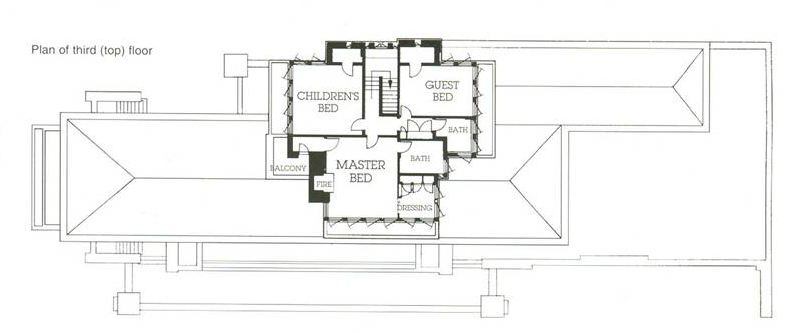

Last level

The rooms are located on this level.

Materials

The house is “wrapped” in Roman brick and limestone.

The enormous eaves are supported by a steel structure, two large beams that run longitudinally are anchored above the chimney.

Wright chose to cover the lateral areas of the beams, leaving a higher area in the center, which produces a spatial effect in both environments.

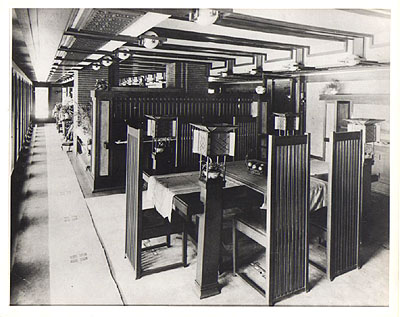

Furniture

All of the furniture in the Robie house was designed by Wright.

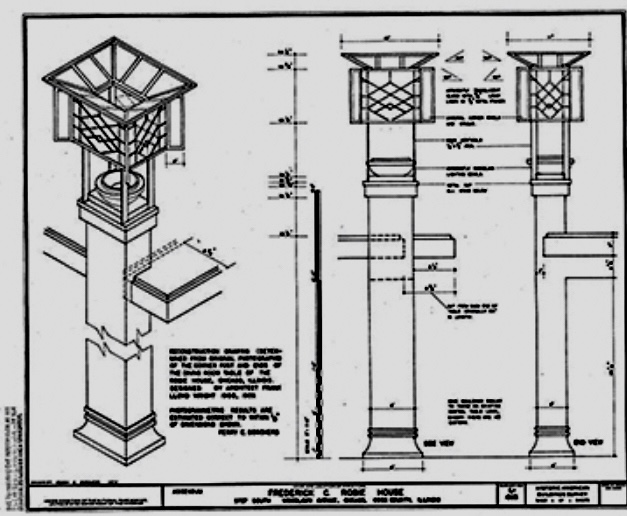

The table rests, in the four corners, on four columns with colored glass lamps and containers for floral compositions.

This design was due to a clear idea: the floral compositions and candelabras that are usually placed in the center of the table constitute a visual barrier between the hosts and the guests.

Here, on the contrary, the decoration and lighting are located in the corners, leaving the center of the table completely free.

On November 27, 1963, it was listed as a National Historic Landmark and since October 15, 1966, it has been part of the National Register of Historic Places in the United States.

In 1992, negotiations began for its restoration and work began in 2002.

“The first thing that catches your attention is the immense roof… covered in tiles… and the dense shadow that reigns under the eaves.” Junichiro Tanizaki (Tokyo 1886 – 1965 Yugawara) “In Praise of the Shadow.” (1933)

http://onlybook.es/blog/el-elogio-de-la-sombra-tanizaki/

“Wright uses the resource of light and shadow to accentuate the long proportions of the eaves and low-sloped roofs, as well as to hide the

bobwindows under an earth-shade color in the shape of a keel and whose side ceilings further accentuate the illusion of extension, achieving an interior-exterior transition and thus merging with the controlled environment.” Adolfo Montiel Valentini. (7)

“…art flows from art and stubbornness, as Leonardo da Vinci recommended. Malraux wrote: a poem at a beautiful sunrise is born from another poem at sunrise and not from contemplation of what the sun does, which is always the same.” Carlos Maggi (8)

joins the battle

Notes

1

In December 1911, David Lee Taylor purchased it for $50,000. He is president of an advertising agency, the house is his wife’s Christmas gift.

Ten months after the purchase, Taylor died, and his wife sold it to Marshal Dodge Wilber, treasurer of a collection agency. In his diary, he points out the deficiencies in the heating, as a record, in the first winter they only managed to raise the temperature to 7 degrees.

Wright said several times that he wanted to buy the house in the 1920s, visited it and, as was his habit, rearranged the books and hid trinkets in unexpected places.

In 1926, Wilber sold it to the Chicago Theological Seminary, they were the last tenants, they held out for 14 years.

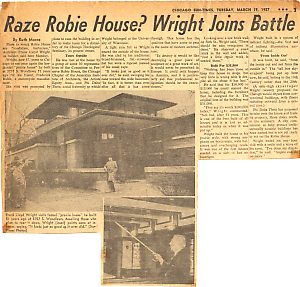

Three decades later, the clergy wants to demolish it. Wright runs a campaign and saves her.

There is a second demolition attempt in 1957 but in 1958 developer William Zeckendorf purchased it and donated it to the Chicago Theological Seminary.

The following year it was declared by House and Home magazine as the best home of the 20th century.

In 1963 it was designated a national historic landmark and donated to the university.

In 2002 it was restored together with the Wright Foundation.

“Early in life,” Wright wrote, “I had to choose between honest arrogance and hypocritical humility. I chose the first and I have seen no reason to change.”

2

Hermann V. von Holst agreed to take on the responsibility of leading Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural firm when he left for Europe with Mamah Cheney in 1909.

Wright had tried to get several architects to take responsibility for his studio, both Marion Lucy Mahony (Chicago 1871 – 1961 Ibid) and George Grant Elmslie (Aberdeenshire 1869 – 1952 Chicago) refused.

He eventually arranged for Hermann V. von Holst to supervise the work, along with architects Isabel Roberts (Missouri 1872 – 1955 Orlando) and John Shellette Van Bergen (Oak Park 1885 – 1969 Ibid.), contractually Marion Mahony would control the entire design. architect and her husband, Walter Burley Griffin, everything related to the urban planning aspect.

The output of Wright’s office in the years 1909-1911 were premier works of the Prairie School by the design team headed by Marion Mahony under the auspices of von Holst (who years later was head of the history department of the University of Chicago).

The aforementioned Isabel Roberts was a member of the design team at Oak Park, along with Marion Mahony and five men – Walter Burley Griffin, William Drummond, Francis Barry Byrne, Albert Mc Arthur and George Willis.

Roberts years later formed the Ryan & Roberts studio with Ida Annah Ryan (Waltham 1873 – 1950 Orlando), one of the first studios made up of women.

3

Metalocus

4

Disgusted with the house, the neighbors ridiculed it by comparing it to a steamboat, pointing out that it had no relationship with the architecture that surrounded it.

It was about to be demolished in 1941, there were protests at the university, which was joined by, among others, Mies van der Rohe (Aachen 1886 – 1969 Chicago). In 1957, the University of Chicago Theological Seminary announced its intention to demolish the Robie House to make way for a dormitory. This provoked the anger of Wright, who, at almost 90 years old, appeared in Chicago to defend the value of its architecture and denounce the demolition plan.

Architects and neighbors supported the efforts and complaints to preserve it, as well as all the architectural treasures of the city, among which the Robie house was included. The National Trust for Historic Preservation also joined. Together they managed to prevent it from being demolished in July 1957.

During the process Wright described the house “as the cornerstone of modern architecture.”

Developer William Zeckendorf (Paris 1905 – 1976 New York) purchased the house in 1958, and later transferred it to the University of Chicago.

His studio Webb & Knapp carried out a redefinition of the neighborhood that, ironically, included the demolition of 880 properties, but not the Robie house.

Among his numerous properties were the Chrysker building in NY, the Astor Hotel.

Both Le Corbusier and Wallace Harrison designed buildings for their firm, Architect I. M. Pei designed his first skyscrapers for Zeckendorf, the Mile High Center (now part of the Wells Fargo Center) in downtown Denver and Place Ville Marie in downtown Montreal .

5

Wiki Architecture data and references.

6

EIn their book Garage, the artist Olivia Erlanger and the architect Luis Ortega Govela maintain that the contemporary garage – just another room, joined to the rest by a door – has its antecedent in this home. Until then these rooms were separated, following the model of stables and garages.

7

Antonio Montiel Valentin. Faculty of Architecture (UDELAR) Architecture and Technology.

8

Carlos Alberto Maggi Cleffi (Montevideo 1922 – 2015 Ibid.) was a Uruguayan writer, journalist, lawyer, historian and playwright. Affectionately nicknamed “el Pibe”.

Our Blog has obtained more than 1,200,000 readings: http://onlybook.es/blog/nuestro-blog-ha-superado-el-millon-de-lecturas/

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico.blogspot.com

Salvemos al Parador Ariston de su ruina

http://onlybook.es/blog/el-parador-ariston-una-ruina-moderna-por-hugo-a-kliczkowski/