hugoklico Deja un comentario Editar

History of the Flatiron Building

From https://onlybook.es/blog/el-edificio-flatiron-de-nueva-york/

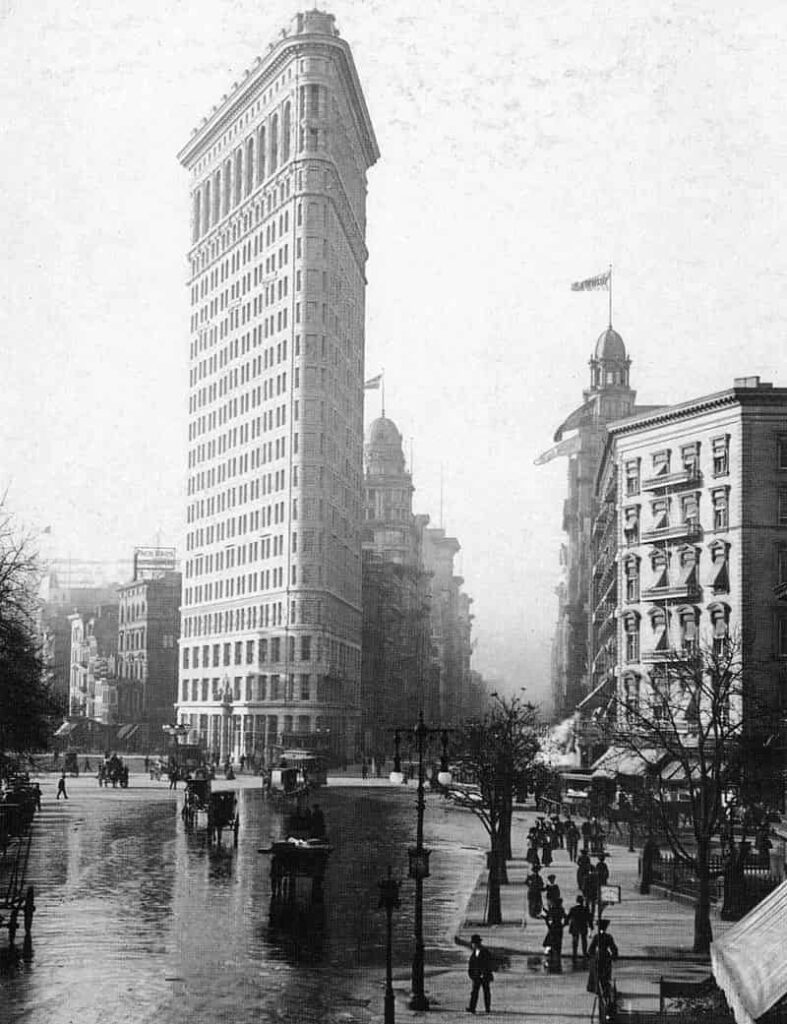

Directly in front of the building is Madison Square Park.

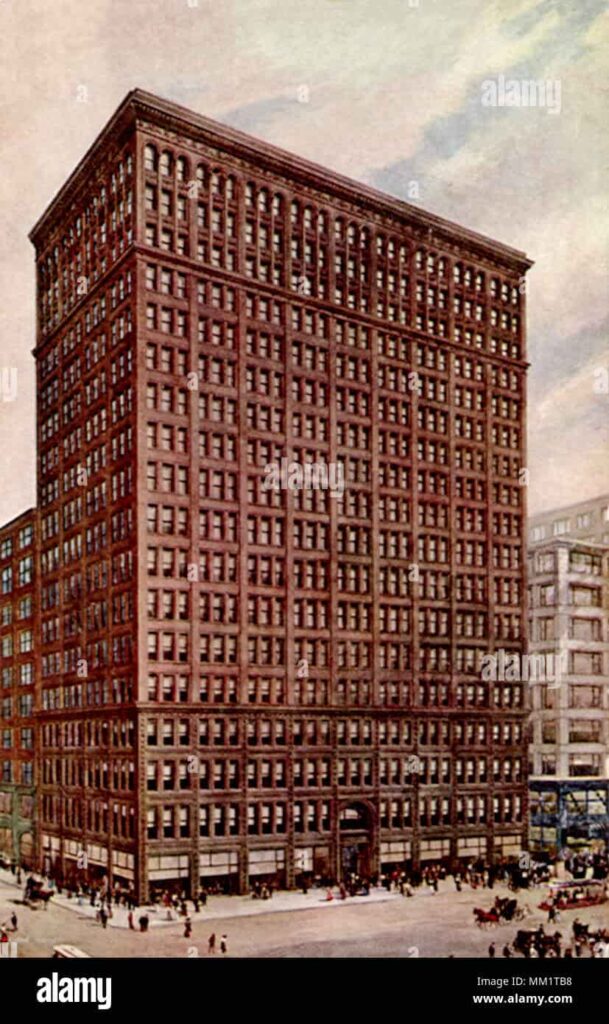

The Flatiron Building was built in 1902 by architect Daniel Burnham (Henderson, USA 1846 – 1912 Heidelberg, German Empire), was designed as a vertical neo-Renaissance palazzo, is famous for its unique architectural design and Beaux-Arts style, its facade is covered in white terra cotta and features ornamental wrought iron details.

The Flatiron Building is one of the first office buildings constructed in New York. In the early 20th century offices in general were dark and crowded, its design was created to address those problems.

The offices in the Flatiron were spacious and bright, thanks to the large windows found on each of the floors. In addition, the building’s triangular design allowed natural light to reach every corner of the building, something that was especially important at a time when electric lighting was not popular.

The location on the corner of Fifth Avenue and Broadway was ideal, allowing city residents to see the building from afar.

The Flatiron Building was not the first skyscraper in New York (there are several criteria for defining what a skyscraper really is), but it was the first to be built in the 20th century.

The Flatiron was initially disliked

One of the most photographed corners of New York was once seen as a tacky building.

There was harsh criticism and bad taste.

The Flatiron Building today

Over the years, the Flatiron Building has undergone many renovations and restorations. In the 1960s, it was proposed to demolish the building in order to build a new one in its place. However, due to pressure from various professional sectors and citizens, it was decided to preserve the building, finally protecting it in 1979 by declaring the building a National Historic Landmark.

In 2019 the building was left without tenants. Its offices were occupied by Macmillan Publishers and since that year it has been under renovation to accommodate new companies that wanted to put their offices there.

Today, the Flatiron Building remains one of the most iconic buildings in New York. Although it has been surpassed in height by many other skyscrapers in the city, its triangular shape and unique architectural design make it stand out in the Manhattan skyline.

-The Flatiron Building was one of the first buildings in New York to have an electric lighting system on its facade, making it visible from many parts of the city at night.

-In the 1920s, an observation deck was installed at the top of the building, which became a popular tourist attraction for many years. Today it is no longer operational,

-In 1974, a small plane collided with the building, causing minor damage and a great commotion in the city.

-The Flatiron Building has been included on many lists of the world’s most beautiful and iconic buildings, and remains a symbol of New York City for more than a century.

-They say that one of the drawbacks of working in the Flatiron was the large draft generated by opening the windows.

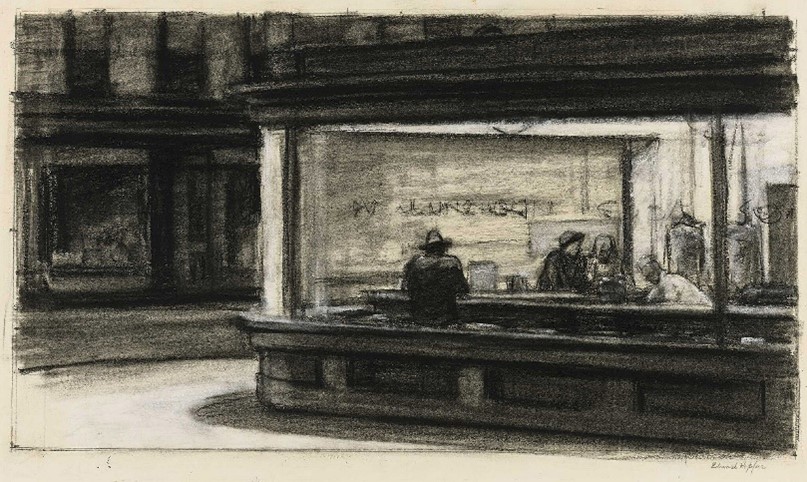

Hopper exhibition at the Withney Museum

-The Flatiron Building has been included on many lists of the world’s most beautiful and iconic buildings, and has remained a symbol of New York City for more than a century.

Hopper exhibition at the Withney Museum

It was open to the public from May 23 to October 6, 2013.

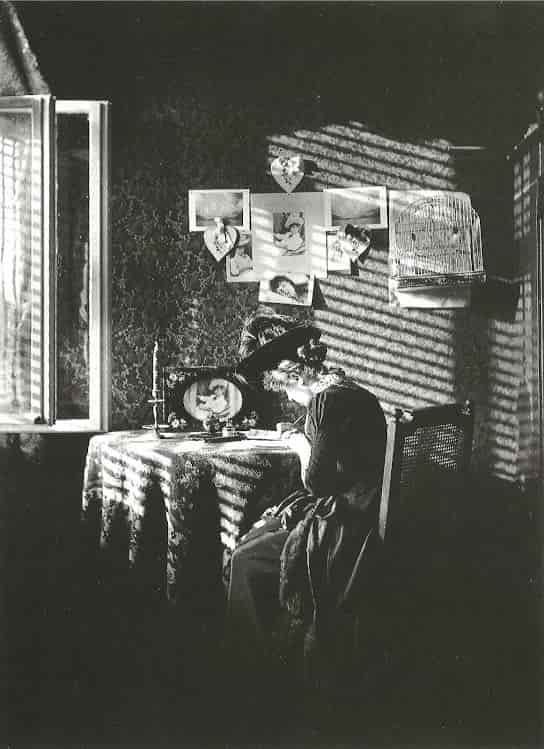

“Hopper Drawing” is the first major museum exhibition to focus on Edward Hopper’s drawings and creative process. More than anything else, «Hopper’s drawings» reveal the continually evolving relationship between observation and invention in the artist’s work, and his abiding interest in the spaces and motifs-the street, the cinema, the office, the bedroom, the road-to which he would return throughout his career as an artist. The exhibition has presented groundbreaking archival research on the buildings, spaces and urban environments that inspired his work.

“Hopper Drawing” was organized by Carter E. Foster, Steven and Ann Ames, curators of drawing, as well as The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Dietrich Foundation, the Selz Foundation, Barney A. Ebsworth, Steve Martin and Anne Stringfield, the Robert Lehman Foundation, Jane Carroll, Aaron I. Fleischman and Lin Lougheed, Arlene and Robert Kogod, and an anonymous donor.

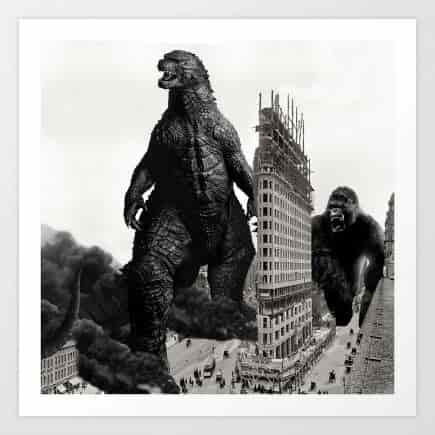

New York Flatiron in film and television

This New York icon is seen in films.

-1998 in Godzilla, where it is accidentally destroyed by the U.S. Army.

-Backdrop for scene changes in “Friends”.

-2002, 2004 and 2007 Spider-Man. He was the Daily Bugle newspaper in the trilogy.

-2007. I am Legend, takes us to a rather black future for mankind, we see places of New York destroyed or totally abandoned as the Brooklyn Bridge, Washington Square, Times Square or the Flatiron Building.

-The building has been used as a filming location for the TV series Mad Men and the movie Men in Black 3.

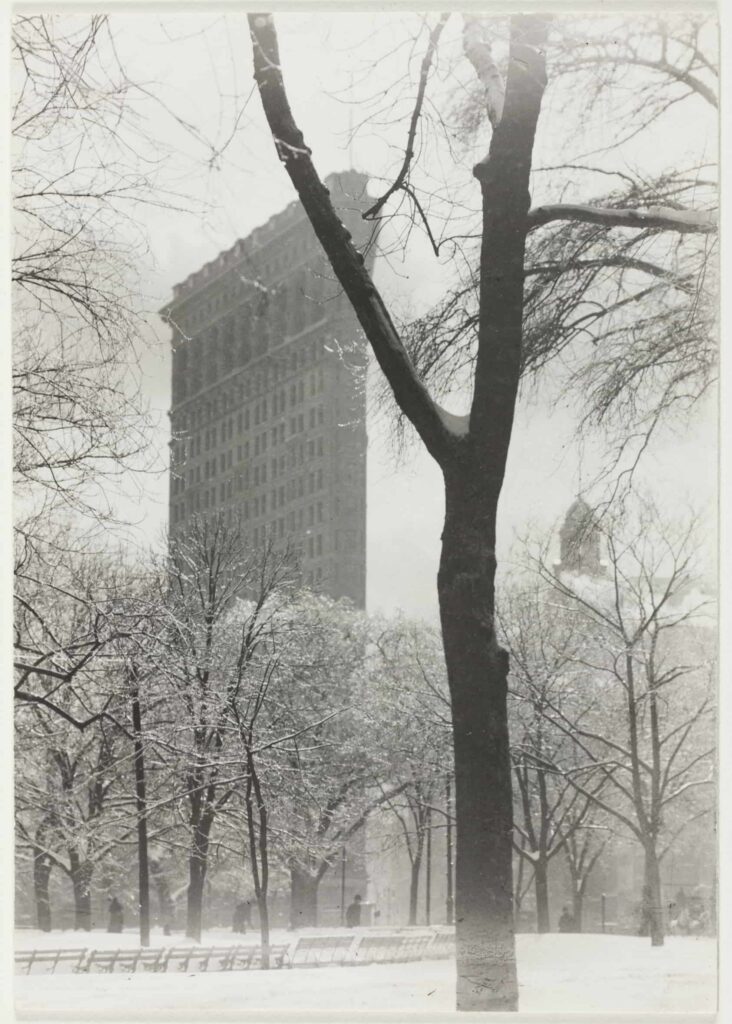

-The building has been the subject of many works of art and photographs over the years, including the famous photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz in 1903 entitled -The Flatiron Building-.

Alfred Stieglitz

In a 1946 article, Stieglitz recalled photographing the newly constructed Flatiron Building on the day of a major snowstorm. “Suddenly I saw the Flatiron Building as I had never seen it before. From where I stood, it looked as if it were moving toward me like the prow of a gigantic steamship, an image of the new America that was being formed.”

The Alfred Stieglitz Collection at the Art Institute, on the website: The Alfred Stieglitz Collection .

New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, “Photography Rediscovered: American Photographs from 1900-1930.” September 19 to November 25, 1979; Trip to the Art Institute of Chicago, December 22, 1979 to February 4, 1980.

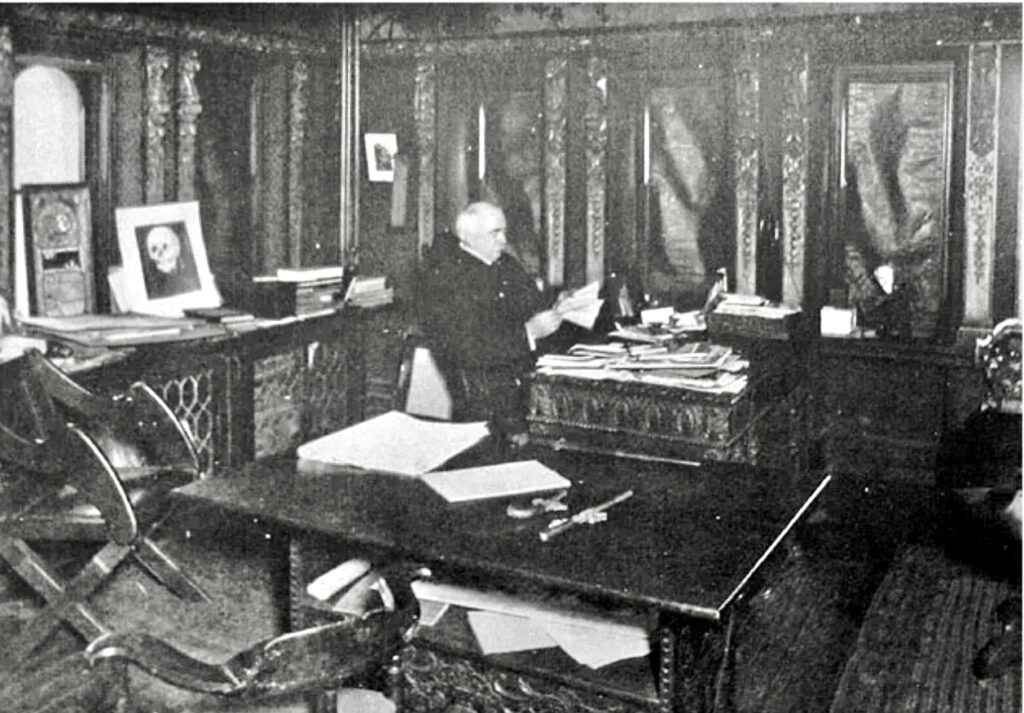

Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz (Hoboken 1864 – 1946 Lake George, NY) was a pioneering photographer, vigorously championed photography as a work of art and established its value as modern art in the United States through his own work, the magazines he published, and the exhibitions he held in influential New York galleries.

He was a member of the jury for the first photography exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, held in 1900. After studying photography in Europe in the 1890s, Stieglitz returned home to New York and turned his camera to the streets and buildings of a rapidly changing city.

“Photography is my passion, the search for truth, my obsession.” Alfred Stieglitz

He printed these images initially as photogravures to emphasize atmospheric effects; later, he published in the fine art magazine Camera Work. During this early part of his career, Stieglitz also favored carbon printing, which produced deep tones and a soft, drawing-like quality.

From 1910 onwards, he adopted more direct images, moving away from a painterly, impressionistic approach. He made use of photographic papers such as platinum, palladium and, later, silver gelatin prints.

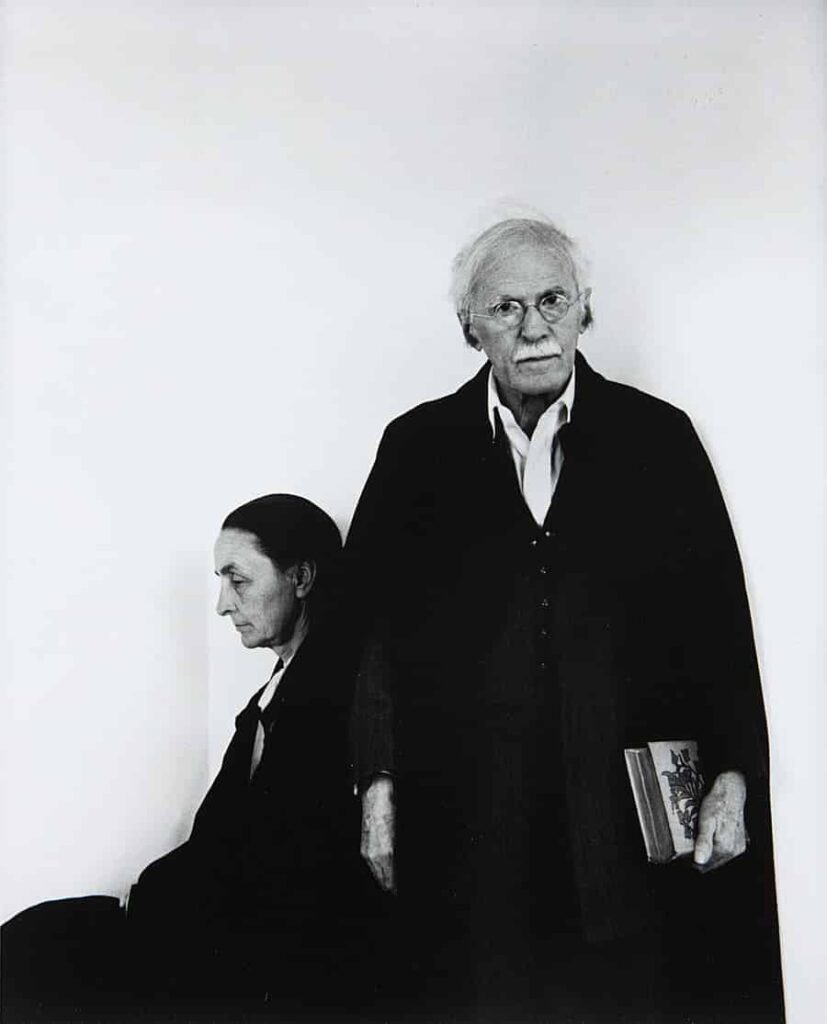

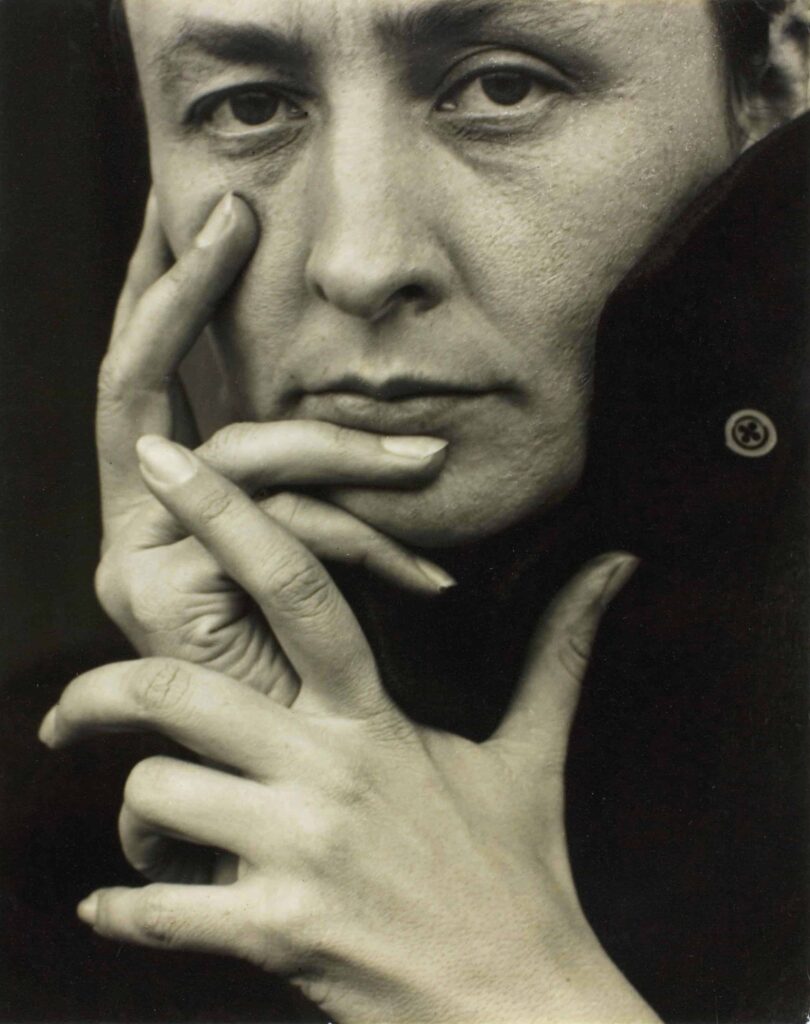

In his portraits of other artists he sought to depict their psychology and not just their likeness. This approach is especially evident in the hundreds of shots he took of his wife, Georgia O’Keeffe, (Sun Prairie, Wisconsin 1887 – 1986 Santa Fe.

See https://onlybook.es/blog/georgia-okeeffe-1era-parte/

Beginning in 1922, Stieglitz also made quasi-abstract photographs with cloud studies he called Equivalents. He saw them as music in pictures, asserting that visual art could be as emotional and non-representational as music. His later work also contained multiple meanings, whether it was a photograph of dying aspens on his family’s Lake George estate that functioned as a meditation on human mortality or of New York City skyscrapers that embodied progress and modernity.

Stieglitz’s formidable activity as a publisher and gallery owner paralleled that of his work as an artist. After serving as editor of the publication Camera Notes, he published his own magazine, Camera Work, which evolved from a showcase for the Photo-Secession to a forum for international modern art of all media. In his galleries-the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, in 1908 the gallery was renamed 291 for the street number on which it was located; the Intimate Gallery; and An American Place, he introduced the European avant-garde and promoted a new generation of American painters, while advocating photography’s place among the other fine arts.

It was one of the first galleries controlled by photographers, a milestone that Stieglitz complemented by exhibiting not only his photographs and those of his close collaborators, such as Steichen, Gertrude Käsebier, and Clarence H. White, but also used the spaces to exhibit

“The Terminal” (1904)

Captured with a camera that professionals detested for being of “poor quality,” Stieglitz selected it because its small format allowed him to carry it more comfortably and adaptable to the ever-accelerating street life.

The photo can be considered another early hybrid between pictorialism and straight photography. Aside from doing street photography in times when the term didn’t even exist, his use of sand, wind or rain, as seen here, to add a softening effect to the image was stimulating.

“As long as there is light, you can photograph.” Alfred Stieglitz

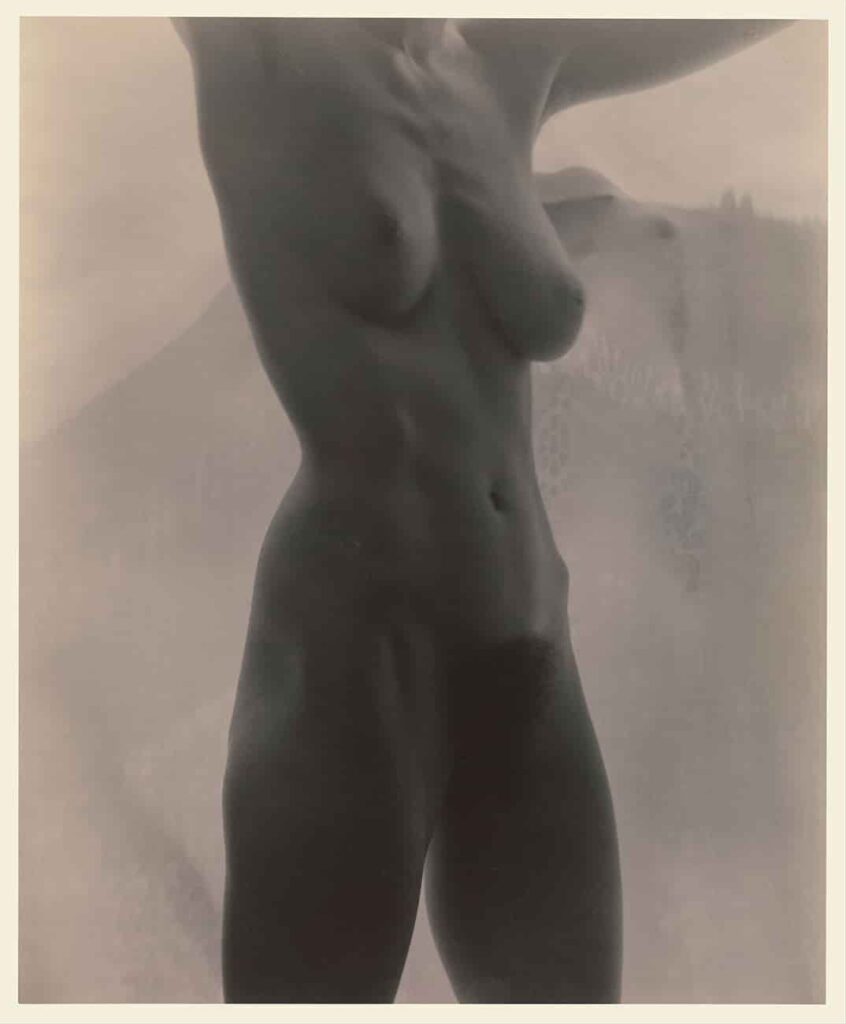

“Torso de Georgia O’Keeffe” (1918-1919)

More than a specific photo, it is a series of photographs that Stieglitz composed of the naked torso of the painter, which he presented in multiple exhibitions. The objective, far from being just a pornographic or fetishistic pretension, was of a technical-artistic nature.

Once again, it was about the exploration of forms in the photographic composition: the framing keeps the woman anonymous in such a way that it is intimate and invites us to observe the lines that form on her body.

The photo-secessionists led by Alfred Stieglitz believed that the camera was a tool just as the brush is for the painter or the typewriter is for the writer.

They made the mistake, however, of initially believing that photography would be more valid as art if it imitated painting, which was what pictorialism advocated, although Stieglitz later switched sides.

“The ability to make a truly artistic photograph is not acquired suddenly, but is the result of an artistic instinct coupled with years of work.”

“The Steerage” (1907)

With “The Steerage”, also known as “The Deck of a Ship” or “The Mezzanine”, Stieglitz wanted to demonstrate that capturing reality in a certain way could have its beauty: what stands out in this photo is the innovative use of shapes and lines with which he composed it.

The work presents German emigrants who were deported from the United States, so they are forced to go to their homeland. He came to consider it his first modernist photograph and promoted it multiple times in Camera Work.

The composition shows two spaces separated by the bridge which, in turn, due to its tone, gains prominence and helps to convey the contrast between the two sides.

The lower view differs from the one above because the white garments come together as a repeated pattern, which does not exist at the other end of the image, which if seen in detail shows that some are privileged classes and the others, below, are less fortunate. (3)

It should be noted that Stieglitz was hardly interested in making photographs of a social or denunciatory nature; he saw in this scene only a set of perfect patterns to compose a great picture.

“My photographs are a picture of the chaos of the world and of my relationship to that chaos. My prints show the constant disturbance of man’s balance in the world, and his eternal battle to restore it.”

Alfred Stieglitz is known to have sat and waited for the scene to look interesting enough. This would also be one of the first times he showed his shift towards straight photography, leaving behind the intentional grain and soft blur that is often prevalent in Pictorialism.

In his words, “Equivalents” was the summary of his forty years of experience in photography. He stated:

“Through the clouds I wanted to put on record my philosophy of life, to show that my photographs were not due to a subject, not due to trees, not due to faces, not due to interiors, not due to special privileges. The clouds are there for everyone, free of taxation until now.”

Stieglitz at the end of his days, directed O’Keeffe to oversee bequests of his work to various museums, including the Art Institute, where he had studied in the 1910s, his collection was donated in 1949, and is part of the permanent photography collection.

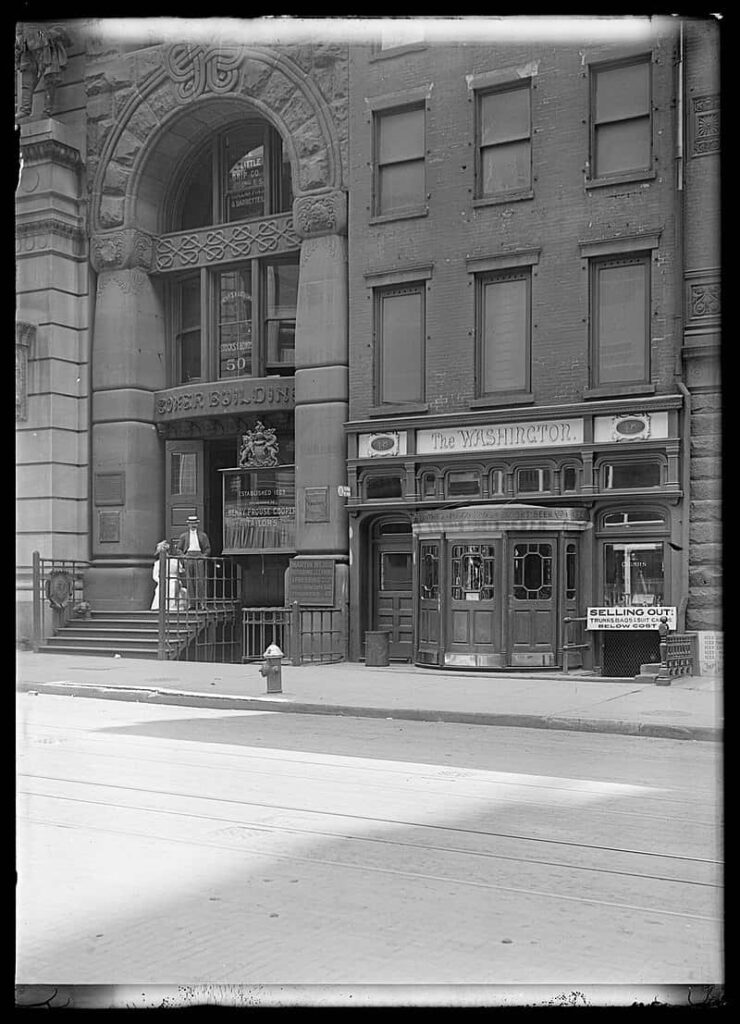

History of the Tower Building. Tower Building 1888/89

The first skyscraper in New York was the Tower Building, with a Steel Framing structure (structural steel) was completed in 1889, had 11 floors, was demolished in 1913/14, Since 1913 it was no longer profitable due to lack of tenants.

The Tower Building was a building in Manhattan’s Financial District. Architect Bradford Gilbert (Watertown, NY 1853 – 1911 NY) submitted plans for its construction on April 17, 1888, it was completed on September 27, 1889.

The Tower Building was a structure in Manhattan’s financial district, at 50 Broadway, on a lot that extended eastward to New Street. It was arguably New York City’s first skyscraper and the first building with a steel skeleton structure.

John Noble Sterns, a supporter of the Cremorne Mission, of which Gilbert was a trustee, hired him in 1888 to design an eleven-story office building in New York City.

For such a tall building, traditional construction methods required very thick walls that would have taken up the land, which was only 20 feet wide. Drawing on his experience with the railroads, Gilbert thought of putting in an end-on railroad bridge, with iron girders to support the floors and exterior walls.

This innovation of “skeleton construction” with “steel-framed curtain walls” allowed him to build a skyscraper without having thick load-bearing walls, and it was also fireproof. Cast-iron columns of about 20 feet (6 m) formed the separate skeleton, and the walls of each floor were “hung” instead of transmitting the load to the wall of the floor below. To circumvent local building ordinances, Gilbert built a four-story base 21 m high, essentially the height of the adjacent buildings, of Little Falls iron and stone, on top of which he constructed ten stories using Philadelphia and Tiffany bricks, with an octagonal roof covered with Spanish shingles. The brick was richly colored and had Celtic ornamentation similar to Mason Stables.

At first it was met with great skepticism, and many predicted said it would collapse, certain engineers declared it “unsafe and impracticable.”

To assure the public of its safety, Gilbert moved his offices upstairs where he stayed for several years. In 1889, Engineering News called it “a very clever solution to an extremely difficult problem.” Ko

A building with traditional construction on the same lot would have only generated $30,000 a year in rent, due to the ten-story height limit and thick walls that would reduce square footage. Because Gilbert had devised a way to double the income from the property, The Philadelphia Inquirer noted that “old Knickerbockers (4) who own real estate on Broadway and other cutting-edge thoroughfares in lower New York have a new god in the person of Bradford L. Gilbert.”

The Flatiron Building New York was not technically the first skyscraper in New York, as is often thought.

This title actually belongs to the Tower Building, which was completed in 1889 and was 11 stories tall. The Flatiron Building was built in 1902, thirteen years later. However, the Tower Building was demolished in 1913 and no longer exists.

Perhaps for this reason it is said that the oldest skyscraper in New York (and still standing) is the Flatiron Building.

The Flatiron Building was designated a New York City landmark in 1966, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1989, further increasing its popularity.

The story of the Flatiron Building begins with architect Daniel Burnham, one of America’s most famous architects, who was commissioned to design and build it with his collaborator Frederick Dinkelberg (1858 – 1035). (5)

His bold design provoked numerous jeers from New York newspapers. The New York Tribune described his work as a “wretched piece of cake” and “New York’s most troublesome lifeless piece.”

See Burnham’s https://onlybook.es/blog/daniel-burnham-y-el-edificio-ellicott-square-en-buffalo/

In 1959, St. Martin’s Press moved in, gradually renting additional office floors and becoming the building’s sole tenant in 2004.

Bradford Lee Gilbert was an American architect, his studio operated in New York City.

Known for designing the Tower Building in 1889, the first steel-framed building and the first skyscraper in New York.

This technique was soon copied throughout the United States.

He also designed the Atlanta International and Cotton States Exposition of 1895, and many railroad stations.

English-American Building

In 1897, Gilbert designed the building for the English-American Loan and Trust Company of Atlanta.

Located at 84 Peachtree Street NW in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, on a triangular-shaped block with eleven stories between Peachtree Street NE, Poplar Street NW and Broad Street NW.

Neoclassical and Neo-Renaissance Revival in style, but modern in form. It was Atlanta’s second skyscraper. The building included three electric elevators, 200 rooms and electric lighting.

It is the oldest remaining steel-framed skyscraper in Atlanta and one of the few non-railroad buildings by Bradfor Gilbert (a contemporary of Daniel Burnham’s Chicago School) that survive today.

It was completed five years before New York’s Flatiron Building. The Flatiron Building is protected by the city as a historic building, listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Gilbert decided to quit college eager to learn architecture, apprenticed beginning in 1872 and apprenticed for five years in the New York City office of J. Cleveland Cady.

In 1876, Gilbert was hired as an architect for the New York, Lake Erie and Western Railroad under engineer Octave Chanute.

In 1890, Gilbert opened his studio at 1 Broadway, New York, he said “It certainly does not cost more […] to design a building that is architecturally correct, of good and quiet contour […] instead of the fancy ‘gingerbread’ work too often adopted; and with interior arrangements designed to meet all requirements.”

Throughout his career, Gilbert also designed apartment buildings, churches, clubs, exhibition buildings, hospitals, hotels, homes, and office buildings.

This attention to detail may have paid off, as many of his other projects grew out of his railroad connections, including the design of residences for presidents of various railroad companies such as William H. Baldwin Jr, Alfred Skitt, Arthur M. Dodge, Benjamin A. Kimball, and William Greene Raoul.

Notas

3

Fotonista. By ANA. April 9, 2024. Alfred Stieglitz, the photographer and gallery owner who changed everything.

4

The Knickerbocker Club (informally The Knick) is a gentlemen’s club in New York City founded in 1871. Considered the most exclusive club in the United States and one of the most aristocratic gentlemen’s clubs in the world.

The term “Knickerbocker”, in part due to writer Washington Irving’s use of the pseudonym Diedrich Knickerbocker, was a synonym for a New York patrician, comparable to a “Boston Brahmin”.

5

Frederick Philip Dinkelberg was known to be a collaborator of Daniel Burnham, in When Harry S. Black of the Fuller Company commissioned Burnham to design a new headquarters for the company on a triangular site in Madison Square in Manhattan, Burnham already had numerous other projects he was working on, and commissioned Dinkelberg to design what was then called the “Fuller Building” but would gain fame as the Flatiron Building. It is not known to what extent Dinkelberg was responsible for the details of the Flatiron Building design, and at the time the design was attributed to “DH Burnham & Co.”

Other major projects he worked on include the Jewelers’ Building in Chicago, and Wanamaker’s Department Store in Philadelphia and New York.

While in New York, Dinkelberg met Charles Bowler Atwood (1849-1895) and, through Atwood, Daniel Burnham. He was hired to work on the World’s Columbian Exposition, where Burnham was the chief builder.

See https://onlybook.es/blog/la-exposicion-mundial-de-chicago-de-1893-la-escuela-de-chicago/

After the fair ended, Burnham hired Dinkelberg to work at his firm, DH Burnham & Company.

There, he designed the Santa Fe Building, known as the Railway Exchange Building, a 17-story office building (1903-1904) and now part of the Michigan Boulevard Historic District.

And the Heyworth Building, a 19-story office building, a landmark in Chicago at the time.

——————-

Our Blog has been read more than 1,300,000 times.

http://onlybook.es/blog/nuestro-blog-ha-superado-el-millon-de-lecturas/

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico.blogspot.com

Salvemos al Parador Ariston de su ruina

Let’s save the Parador Ariston from its ruin

http://onlybook.es/blog/el-parador-ariston-una-ruina-moderna-por-hugo-a-kliczkowski/

Entry navigation

Entrada anterior GB. The Flatiron Building in New York City (mb)