hugoklico Deja un comentario Editar

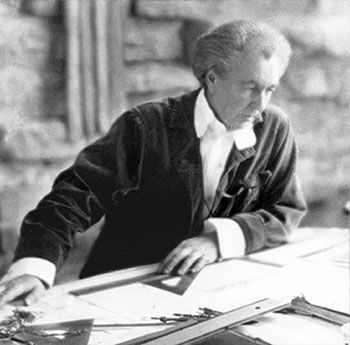

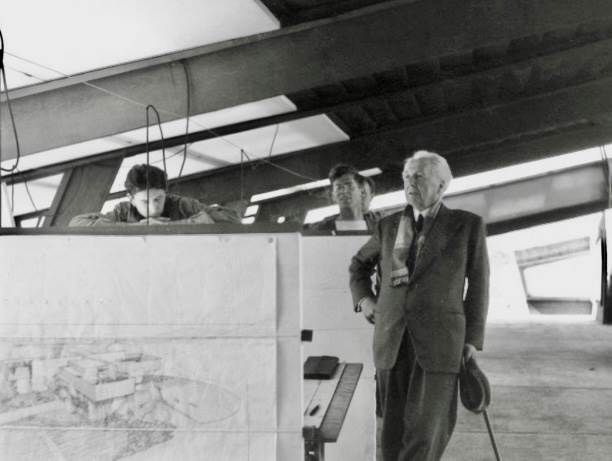

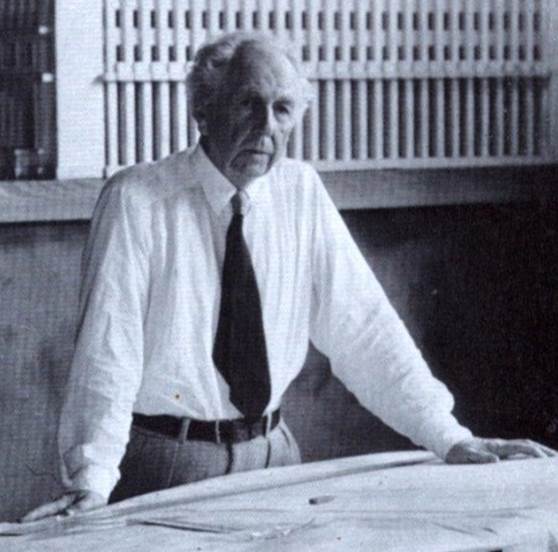

Wright was aware of the importance of his buildings and his projects. When he declared that he wanted to be not just «the greatest architect in the world, but of all time,» he was reflecting his opinion about how his architecture would change the vision of modern architecture.

«I promise to be the greatest architect that ever existed in the world, as well as the greatest of all who will ever exist; that is, the greatest architect of all time.»

In a 1955 television interview, a journalist overhears an 88-year-old man reply:

«You see, young man, I’ve been accused of claiming to be the greatest architect in the world… And if I said so, I don’t think I was being too arrogant.»

To disseminate his work, he spared no effort, exhibiting, publishing, books, and articles. He was a popular lecturer, invited to interviews. To further strengthen his efforts, he designed his signature tool, the Wasmuth Portfolio.

In his life, events «happened,» moments overlapped, which is why this article is organized in the order it is: simultaneous.

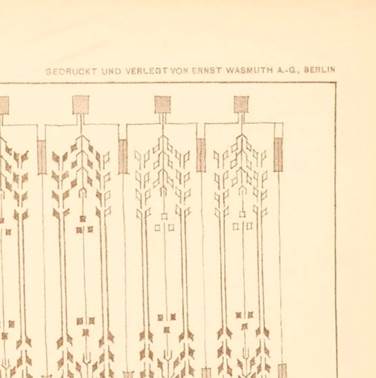

Catalog. Complete Volumes I and II. 1910 and 1911

J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, University of Utah.

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=204451&q=wasmuth

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=204452&q=wasmuth

Cover, Volume 1

Wasmuth Portfolio, 1911. Lithograph on paper, 50.8 x 76.2 cm

Frank Lloyd Wright, Berlin, Volume I (52 plates, 41 x 64 cm) / J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

Wasmuth Portfolio

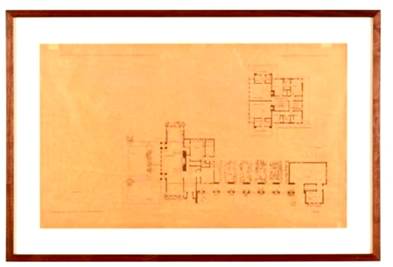

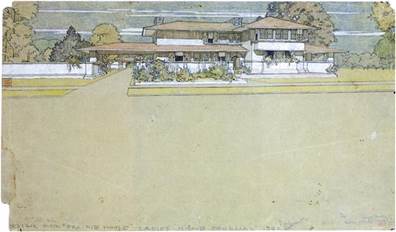

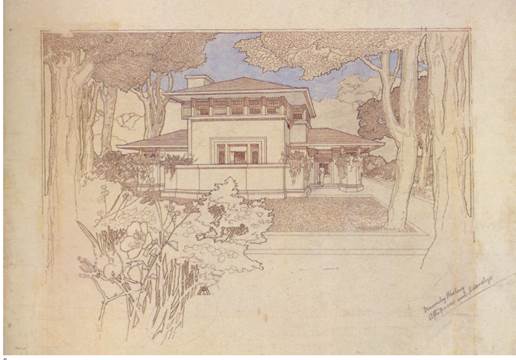

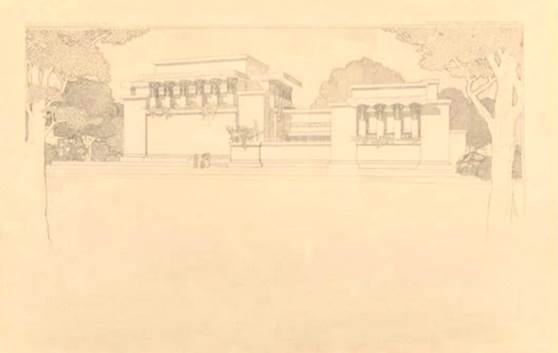

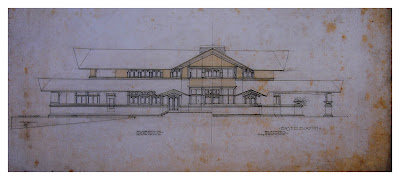

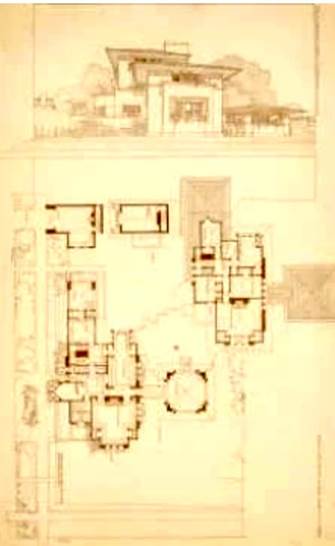

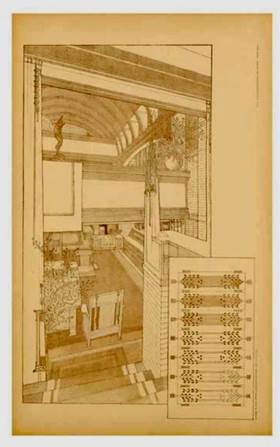

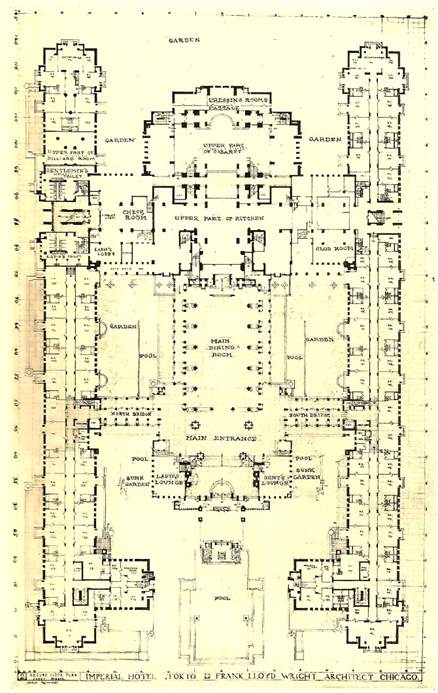

This was a lavish, large-scale, two-volume illustration, with 100 lithographic plates, 64 x 41 cm. It included Wright’s most famous buildings, most of them completed and others unfinished.

“Designs for Executed Buildings and Designs by Frank Lloyd Wright” (Designs for Executed Buildings and Designs by Frank Lloyd Wright), produced in Berlin by art book publisher Ernst Wasmuth (1845–1897), who five years earlier had published the Viennese Art Nouveau works of Joseph Maria Olbrich, is undoubtedly one of the most significant legacies of 20th-century architecture.

See the Francis and Mary Little House in the Met https://onlybook.es/blog/wright-met-casa-francis-y-mary-little-7ma-parte/

At 44, Wright thus further strengthened his reputation as one of the most prominent and influential modern architects internationally.

It is important to note that this was Wright’s first publication abroad, as he had not published any books or works of his own in his previous twenty years of activity in the United States.

See this article about The Works of Frank Lloyd Wright, the Tom Monagham Museum, the Wasmuth Portfolio, and the Murder at Taliesin. https://onlybook.es/blog/las-obras-de-frank-lloyd-wright-parte-5/

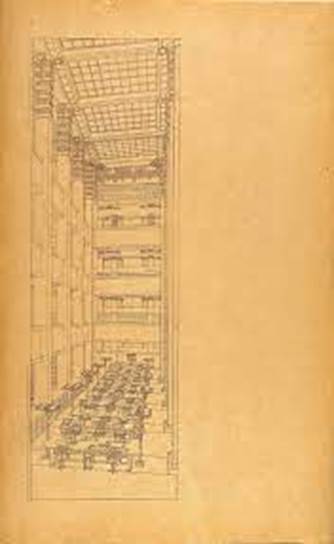

The drawings were printed using the largest lithographic prints available. The task was enormous, as they had to be retouched with pen and ink, adapting the plans, elevations, and drawings to a standardized format for publication.

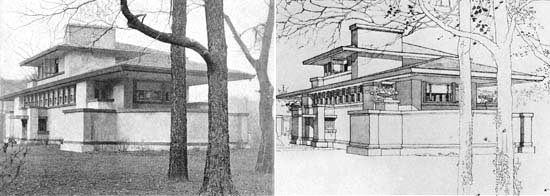

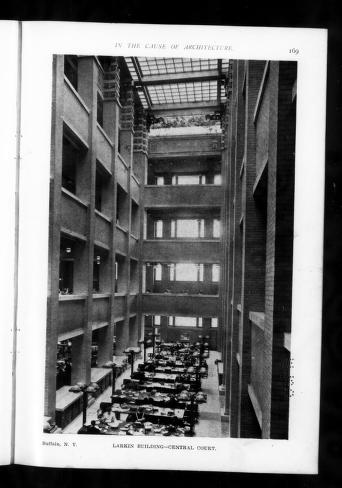

Many of Wright’s most important works are represented there, such as the Frederic Robie House, the Susan Lawrence Dana House, the Ward Willets House, the Darwin Martin House, the Avery Coonley House, the Larkin Building, and the Unitarian Temple.

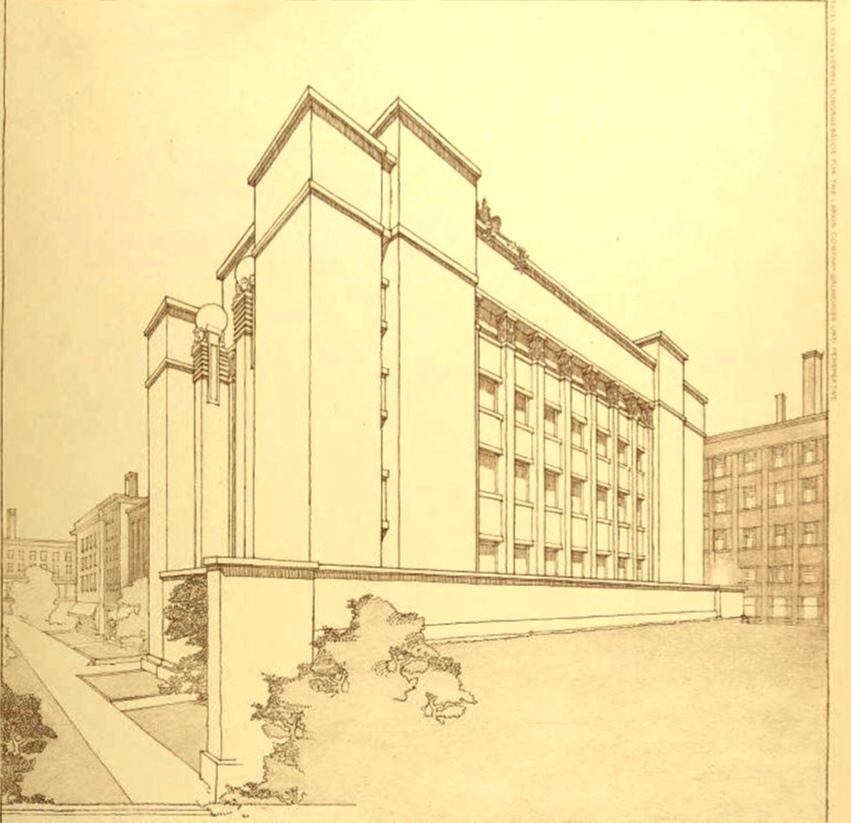

Historian and professor H. Allen Brooks (14)

These are drawings made expressly for the publication and, as has been verified (H. Allen Brooks, in The Art Bulletin, vol. 48, no. 2), many of them were made from photographs of the actual building. (10) Of the 34 projects published in the magazine, 28 coincide with those published in the Portfolio. Of these, Wright chooses photographs of 10 works to redraw them. They are intentional drawings where he highlights with graphic values what he really wanted to show of his architectural style, as well as the tripartite order of architecture: base, body, and capstone. «My drawings are intended only to show the composition in outline and form, and to suggest the atmosphere of the surroundings.» (15)

Brooks’s article attempts to differentiate the drawings of each of the draftsmen who apparently participated in the work (five in total, including Wright himself). It is evident, however, that despite the involvement of different draftsmen, the character of all the plates is similar, at Wright’s express wish. It is also known, from the testimony of his collaborators, that he did not stop until he considered a drawing to be correct, working alongside each of the draftsmen.

Article by H. Allen Brooks in The Art Bulletin

Below is part of the article… Never before has there been so much interest in Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural drawings as there is today.

In recent times, more major publications and exhibitions have been devoted to his drawings than to his architecture, and these drawings of buildings, rather than photographs, are increasingly being used to illustrate his work.

This enthusiasm has been reflected in the dizzying price (now quoted in four figures) of Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright, the portfolio… that serves as the basis for this study.

It was reissued in 1963 by Horizon Press, which had already published a luxurious color edition of Frank Lloyd Wright Drawings for a Living Architecture in 1959.

The year 1962 saw a major exhibition of Wright’s drawings at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the simultaneous publication of a book/catalogue by Arthur Justin Drexler (1925–1987), who was MoMA’s curator and director for 35 years.

The book/catalogue illustrated the 300 drawings in the exhibition, which ran from March 14 to May 6, 1962. The exhibition later traveled to other cities in the United States and Canada.

The Book/Catalog

Yet, despite all this attention, we know little about the drawings. In most cases, their authorship remains dubious.

Wright never claimed that they were entirely his work; indeed, he was always very magnanimous in acknowledging his assistants’ skill in representation.

But the recent spate of books and exhibitions, which assume such dogmatic titles as The Drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright and Frank Lloyd Wright Drawings (11), has done much to confuse the matter and to mislead the public into believing that what is depicted is the work of the master.

The book says, our present analysis, therefore, is an initial attempt to bring order to this perplexing problem.

Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street, New York

Wednesday, March 11, 1962

Two hundred fifty original drawings by Frank Lloyd Wright, a unique exploration of his accomplishments from 1895 until his death in 1959, were on view at the Museum of Modern Art from March 11 to May 6. The drawings were selected from more than 8,000 items in the archives of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation at Taliesin, the architect’s home and studio in Wisconsin. “Few architects in history have been as convincing in presenting their buildings as painterly images as Frank Lloyd Wright,” says Arthur Drexler, director of the Museum’s Department of Architecture and Design. “His drawings often reveal his intentions more clearly than photographs of completed buildings. But in addition to their value in illustrating the architect’s purpose, Wright’s drawings possess an intrinsic beauty; they are works of superb draftsmanship, skillful composition, and often unexpected delicacy.”

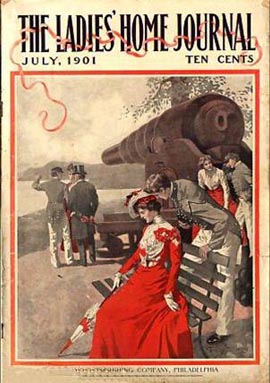

Wright was aware of the importance of these magazines in reaching a large audience of potential customers, as well as the appeal that these drawings could have.

He published four projects in the magazine, and readers could purchase copies of the drawings for 5 dollars.

The Ladies’ Home Journal, July 1901

Made by Wright himself or by draftsmen under his close supervision, these drawings were part of his daily design process, in which he studied the effects of composition, mass, and texture. Most of those shown are perspective views that Wright required for his own study purposes; others are formal renderings prepared for presentation to his clients.

Note text…The exhibition has included drawings of numerous unbuilt projects: terraced gardens and ranch-style developments; summer cottages for California and glass-walled skyscrapers for New York; a steel cathedral; a community center for Pittsburgh; hotel towers for Washington, D.C.; designs for an automobile, a helicopter, a coffee cup; and a few technical details of special interest. The exhibition concludes with some examples of the work being done by Taliesin Associated Architects, the group of Wright’s former colleagues and students who continue the practice of architecture according to the principles he established. Wright held that the quality of depth, of physical expanse through and around space, is best conveyed by the horizontal plane. Photographs of his finished buildings, Drexler notes, do not always clearly show the interrelationship of vertical and horizontal elements, and in his drawings Wright rarely attempted to depict their location in space with literal accuracy.

Instead, he developed graphic representation techniques comparable to those found in the Japanese paintings and prints he admired and collected. Broad areas of color, an ingenious, intricate, and refined use of line, and a great emphasis on natural accuracy are hallmarks of Wright’s graphic style. Even the most sprawling buildings are usually shown from a distance wide enough to encompass the entire structure and its surrounding terrain. «The landscape,» Drexler continues, «was inseparable from Wright’s idea of architecture, and in some of his most beautiful drawings, the landscape seems to have been created and revealed by the buildings. With each subject he explored, Wright revealed a new world of possibilities. The drawings in the exhibition allow us to follow the development of these ideas, and the composite picture they produce is of forms in harmony with nature, still capable of growth and change, and perhaps now more relevant than ever to the art of architecture.»

“Drawings by Frank Lloyd Wright,” selected and installed by Wilder Green, Assistant Director of the Department of Architecture and Design, is the Museum of Modern Art’s sixth exhibition devoted entirely to his work. Numerous examples of his buildings have also been featured in traveling exhibitions, including the recent “Visionary Architecture.” A chair Wright designed for the Larkin Building is currently on display in the Museum’s second-floor galleries, where a selection from the Museum’s own collection is on view.

Horizon Press has published a book of 300 Wright drawings, edited by Arthur Drexler, for the Museum to mark the exhibition

Among Wasmuth’s drawings, the perspectives are mostly from eye level… several are «bird’s-eye» views, and a few are «worm’s-eye» views from below. But the process by which many of the eye-level perspectives were created is so unexpected and, at the same time, so obvious that it has gone unnoticed until now.

Some of the drawings are simply copies of photographs. The most striking example of this is the Tomek House, as can be seen by comparing Wasmuth’s drawing with an earlier photograph.

The fidelity of the copy is extraordinary… it encompasses the surroundings. Every tree has been carefully traced, including its branches and hairy bark. The house is the same, line for line, even down to the open bedroom window. The only additions are vases of flowers on either side of the porch and a change in the direction in which the shadows fall.

Architectural Record 1908

The photograph from which this drawing was copied was published with Wright’s article «In the Cause of Architecture» by the Architectural Record in 1908. A further comparison of these 1908 photographs with Wasmuth’s drawings reveals that no fewer than ten of Wasmuth’s plates are derived directly from this single photo source.

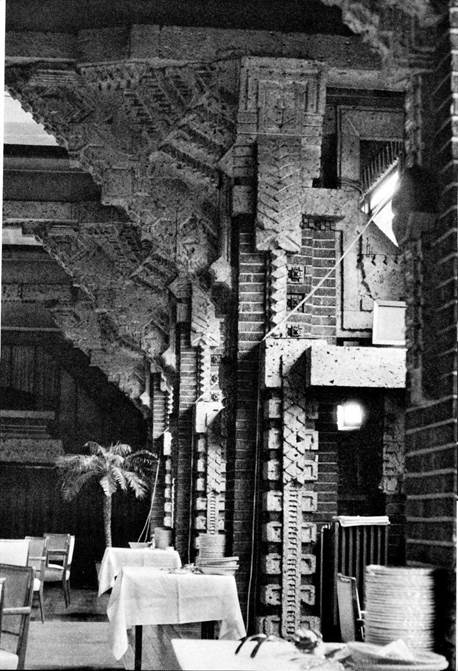

Not only exterior views were included, but also interior views (12).

See the 1908 Record Magazine https://archive.org/details/sim_architectural-record_1908-03_23_3/page/222/mode/2up

This evidence suggests that most of the eye-level perspectives, when made after the building was completed, were derived from photographs. Sometimes the manner of reproducing the foliage—tree leaves, plants, and vines—was also similar to the photographic image. The fact that Wright was a keen amateur photographer no doubt helps to explain his awareness of the camera image. (13)

…Only in the reproduction of the foliage, which is what gives these drawings their unique quality and charm, can individual hands be distinguished. is what gives these drawings their unique quality and charm can that hands be distinguished?, … each representation was not always the responsibility of a single draughtsman. Sometimes the work was a group effort, but in such cases the apprentice usually followed the existing style so closely that his contribution was not obvious. Barry Byrne (1883 – 1967), who worked in Wright’s studio from 1902 to 1907, executed numerous perspective drawings of buildings and occasionally drew the surroundings, but in doing so he adopted the style of Mahony and Wright with such skill that it is impossible to determine today which drawings he helped to prepare…

He was involved in important Wright buildings such as the Unitarian Temple and the Coonley House. Wright gradually left his studio due to his relationship with Mamah Cheney; the instability of the studio work was the reason Byrne left his position.

Wright made more than one view of the same project to verify different aspects of the proposal. He chose different viewpoints to study the volume, interior spaces, the relationship between elements, or the situation in the environment. These drawings served to refine, develop, or confirm an idea. The following is a drawing of the Kaufmann House or Fallingwater, in Mill Run, Pennsylvania, from 1935.

Wright and Japanese Art. He was a collector and dealer of Japanese art.

Sans Soleil Editions. “The Japanese Print”

Author Ander Gondra Aguirre, 104 b/w pp. 1st edition October 2018

In 1912, Wright published a short essay in Chicago entitled The Japanese Print: An Interpretation. Wright found in Japanese culture a path to understanding and developing the relationship between architecture, geometry, and nature.

The book reveals Wright’s interest in popular Japanese printmaking (ukiyo-e, the Japanese print), especially the great landscape artists Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), Andō Hiroshige (1797–1858), Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806), and Suzuki Harunobu (1724–1770).

Ho-o Pavilion at Expo Chicago

In this development of Japanese culture and Wright, we must remember that 1893 was a key year, as the World’s Fair was held in Chicago, in which Japan participated, building an architectural work that was a replica of the old Japanese building (11th century) called Ho-o-den, or Phoenix Pavilion. Wright had access to this exhibition and was able to contemplate the Japanese architecture, in which he had already begun to take an interest, as well as the different pieces such as tapestries, sculptures, carvings, ceramics, prints, and photographs that were displayed in the Japanese section of the Fine Arts building.

When Wright created his first works known as prairie houses, some of his constant characteristics were present, such as the predominantly horizontal conception, the interior space organized around two intersecting axes, and the extension of the roof into wings that form porches or eaves.

Architect Daniel H. Burnham (1846-1912), who worked on this exhibition, commented on it: “The Fair… is going to have a great influence on our country. Americans have seen the classics for the first time on a large scale… the fair has shown that while… the way of Sullivan and Richardson is good enough, their way will not prevail—architecture is going the other way…”

In the 1880s, merchant Siegfried/Samuel Bing (1838-1905), a dealer in Japanese objects, opened a shop selling oriental goods in New York. It was around this time that Wright began his collection of Japanese art, especially ukiyo-e prints.

But Wright was not just an aficionado of these creations; he was also a true scholar and a skilled professional salesman, importing more than 20,000 works for major museums and collectors in the United States. This direct contact with Japanese prints decisively influenced the birth of organic architecture.

Some of his most famous creations, such as Fallingwater (1936), exemplify the lessons learned from Japan. Frank Lloyd Wright lived surrounded by Japanese prints.

The book is introduced by an essay by David Almazán Tomás, professor of East Asian Art at the University of Zaragoza, and then a translation of the essay The Japanese Print: An Interpretation, written by Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago in 1912.

In the first 1974 catalogue of Wright’s work, William Allin Storrer, four of Wright’s most important works in Japan are published: the residences of Aizaku Hayashi (1917 S206), general manager of the Imperial Hotel; the Arinobu Fukuhara (1918 S207) (demolished); and the Tazaemn Yamamura (1918 S212), which is preserved in its entirety in Ashiya, Hyogo Prefecture; and the Imperial Hotel (S 194), which is partially preserved on Meiji Mura Island. In addition to the Jiyu Gakuen girls’ school in 1921, founded by his disciple Arata Endo.

See article https://onlybook.es/blog/wright-en-el-museo-meiji-mura/

Wright made his first trip to Japan in 1905, then in 1913, and between 1915 and 1922 during the construction of the Imperial Hotel he made several trips during which he carried out 12 projects of which 7 were completed.

The Metropolitan Museum of New York dedicated its Fall 1982 Bulletin to Frank Lloyd Wright, a work that was coordinated by Edgar Kaufmann JR (1910 – 1989) who lived in Fallingwater and collaborated with Wright on the Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship, and Julia Meech-Pekarik. It was edited in gratitude for his donations and sales of works to that institution. In the bulletin, researcher Julia Meech-Pekarik studies Wright’s work as a collector of Japanese prints, many of which were donated or sold to the Museum. The same author curated the exhibition Frank Lloyd Wright and Japanese Prints: The Collection of Mrs. Avery Coonley,16 held in 1983, which featured the prints Wright sold to Mrs. Avery Coonley (1874–1958). (16)

In September 1957, in a talk with her apprentices, she told them, “I remember when I first became acquainted with Japanese prints. That art had a great influence on my feelings and thoughts. Japanese architecture not at all. But when I looked at those prints and saw the elimination of insignificance and the vision of simplicity, along with the sense of rhythm and the importance of design, I began to see nature in a totally different way.”

Despite saying that the influence of Japanese architecture did not influence his work at all, there are several studies by historians and critics who claim to understand that it did, such as the tendency towards simplicity, horizontality, the great prominence of the roof with its wide eaves, the taste for white volumes, the appreciation of simple and perishable materials such as wood, plaster, clay tiles for roofs, the structure in wooden columns, the spatial fluidity (enhanced by mobile separating panels), the dim light inside the buildings; and the intimate connection with nature. (18)

In 1911, Wright invited his friend, the Arts and Crafts artist C. R. Asbhee, to present an exhibition, and Asbhee gave his opinion on what he understood to be the Japanese influence on Wright: “The Japanese influence is very clear. Wright is obviously trying to adapt Japanese forms in America, although the artist denies it, and the influence must be unconscious«. Wright responded, “My conscience is pricking me—I do not say that I deny that my love of Japanese art has influenced me—I admit that it has, but I claim to have digested it. Do not accuse me of trying to ‘adapt Japanese forms’; however, it is a false charge and against my very religion.”

“As I became more familiar with the native houses of Japan, I detected the stripping away of the insignificant… The Japanese house fascinated me, and I spent hours taking its parts apart and putting them back together… I found very little to add to the Japanese residence in the way of ornamentation…as they are not necessary to bring out the beauty of the simple materials used in their constructions. At last, I found a nation on earth where simplicity, unadulterated, is supreme.” (17)

At the time of Wright’s death, he owed money to several Asian art dealers in New York, and his collection included over 6,000 Japanese prints, some 300 Chinese and Japanese ceramics, bronzes, sculptures, textiles, stencils, carpets, and over 20 Japanese and Chinese screens. At Taliesin, they found a box of over 700 surimono, high-quality, small-run prints. They also found in Olgivanna’s suitcase numerous Japanese fabrics, acquired by Wright during his stay in Tokyo building the Imperial Hotel (1915-1922).

Wasmuth Portfolio Introduction

To accompany the plates, Wright wrote an introduction in English and German. His writing was the product of months of contemplation of the project, lasting even longer than the portfolio compilation process itself.

In it, he assessed his own work, commented on education, historicism, and the importance of organic architecture. In fact, the essay was so dense and poetic that Wasmuth had difficulty translating it into German.

The first edition had a foreword by the English architect Charles Robert Ashbee (1863–1942); a second edition was published in 1924.

How the story begins

In 1909, German Harvard aesthetics professor Kuno Francke visited Wright in Oak Park and offered him a trip to Berlin to hold a major exhibition of his work. Following a fruitful period of professional activity in the so-called Prairie style, with around 140 works produced between 1893 and 1909, he warned him, “My countrymen are interested and groping, only superficially, for what I see you doing organically: your countrymen are not ripe for you. Your life will be wasted here. But my countrymen are ripe for you. They will reward you. It will be at least fifty years before your countrymen are ready for you.”

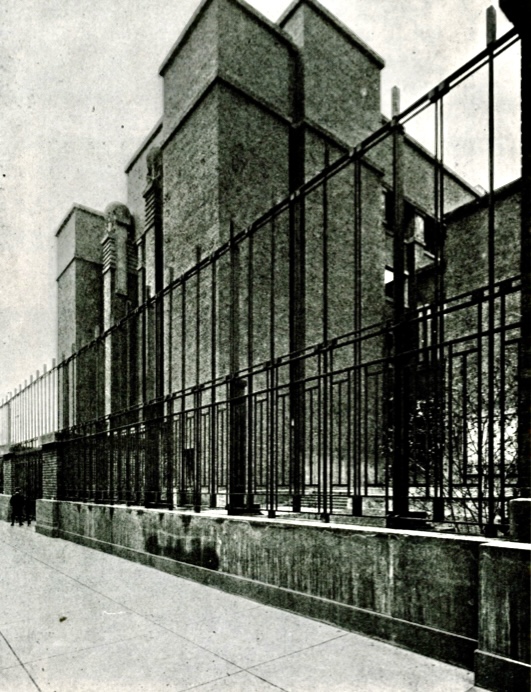

This assessment contrasted with the opinion of Russell Sturgis (1836–1909), the most famous architectural critic in North America at the beginning of the century, who expressed surprise when evaluating the Larkin Building, which Wright had built in 1904 for a mail-order company; a surprise that led him to dismiss it as extremely ugly.

The qualification “Ugly” is strange; it would also be like saying “Beautiful.” Being a work of architecture a compendium of forms, functions, and cultural and urban responses, these exceed the possibility of qualifying it in those terms. Wright wrote in this regard, “Architectural taste is a matter of ignorance.”

The sociologist and historian Lewis Mumford Mumford (1895 – 1990), one of the most brilliant critics of architecture and the city in North America, noted in a more passionate tone: “(Wright) ( … ) challenges us by running the risk of failing in his new design instead of seeking security or seeking perfection ( … ) this prodigality is what makes his architecture so difficult to accept for a timid generation that is in pursuit of security ( … ) Wright, more than any other architect, has contributed to produce a change in our attitude to American art, a shift from colonial dependence on European models to faith in our national capacities, from the cult of the partially historical to confidence in the living present, from formality and neatness in our style of life to directness, animation and repose.”

Among the disparagements or undervaluations of Wright’s work in North America is the opinion of Philip Johnson, who barely concealed his contempt for Wright’s work when he defined him as «the greatest architect of the 19th century.»

Wright immodestly stated, «The fact that modern architecture originated with a contemporary from Chicago was not something that could be tolerated.»

His contribution to breaking the spatial «box» was very important; see the article https://onlybook.es/blog/las-obras-de-frank-lloyd-wright-parte-10-wright-pensaba-en-3-dimensiones/

In 1910, after a personal crisis that led him to leave his wife and six children and in search of new horizons, Frank Lloyd Wright decided to go into voluntary exile for a year in Europe, accompanied by Mamah Borthwick, the wife of his client Edwin Cheney, whom Mamah abandoned for Wright.

They both left their children in the United States.

They rented a villa on the outskirts of Florence to prepare the drawings and prepare for the publication of his monograph, which would make him the most renowned architect and a pioneer of modern American architecture.

See https://onlybook.es/blog/las-obras-de-frank-lloyd-wright-parte-8-su-vida/

The edition impressed with the quality of its artwork and illustrations, and the thematic concepts developed in its preface, «Studies and Executed Buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright,» written during his stay in Florence in June 1910.

There, he established the principles of his new organic architecture. The Japanese influence in his work and representational styles is clear; it was perfectly in line with Wright’s approach during that period, known as «The Early Period (1893-1909)» or «The Prairie Style.» There are references to the Impressionist painting movement, manifested through color renderings, mostly created by Marion Mahony in his Oak Park studio.

They were masterfully adapted and compiled in the Wasmuth portfolio, using a unique printing system (lithography) where the perspective of the work in the landscape was combined, on certain occasions with plants and/or details in a single plate, or a partial position of the painting, turning each representation into a work of art in itself, preceded by a list of numbered plates, with descriptive texts of each work and project that were added to Wright’s preface.

Wright personally supervised the execution of the lithographic drawings that needed to be redone for a year, assisted by his son Lloyd. It was also necessary to move Taylor Woolley, one of the draftsmen from the Oak Park studio, to Florence, who, using as a basis the color originals executed by the architect Marion Mahony, recognized as the best graphic artist who accompanied Wright in the early years of his career and who is recognized as one of the main protagonists in the consolidation of the Prairie style.

Video B. Harley Bradley House https://youtu.be/ivy_HOoaGAk

There is no specific order in the Portfolio; the works do not appear in chronological order. Among the earliest are the Winslow House, the first project he completed upon opening his own studio in 1893, the Francis Apartments, Lexington Terraces, Hillside Home School, Riverforest Golf Club, Riverforest Tennis Club, and the Citi National Bank.

“Buildings, like people, must first and foremost be sincere, they must be authentic, and also as attractive and beautiful as possible.” F. Ll, W.

Print run

The original edition, initially planned for 1,000 copies, was reduced to 650 for budgetary reasons, with 25 larger «deluxe» copies printed on paper and with a gold-lettered cover. Of these, 150 were distributed in Europe, while the remaining 500 remained in the Taliesin office until the fire in 1914, from which 35 copies and some loose plates were salvaged.

In 1911, a German edition known as ‘Little Wasmuth’ and an even smaller Japanese version were published, which expanded the scope of his work. The Wasmuth Portfolio gave Wright a notable reputation and prestige in Europe, the United States and Australia both for his works and for his conceptual manifesto, becoming one of the driving forces of modern architecture and exerting enormous influence on European architects of the beginning of the century, particularly Mies van der Rohe in the initial brick-making period in Germany, who would state “…Wright’s work presents an architectural world of unexpected force, clarity of language and bewildering richness of forms”, as well as the incipient activity of the Dutch group De Stijl, founded by Theo van Doesburg in 1917 and inspired by Wright’s more abstract images such as the perspective of the Yahara Boathouse for the University of Winconsin Boat Club, Madison, Wisconsin, 1902/05; the perspective of the Larkin Company Administration Building, Buffalo, New York, 1903/05; and the illustrated presentation of the Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois, 1906/09, and undoubtedly influencing to a lesser extent, Walter Gropius and Charles Edouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier).

Upon his return to Oak Park, Chicago in 1911, the situation was not suitable for restarting his career and, induced by a plot of land given by his mother in Spring Green in the Wisconsin Valley, an area where he had already built a windmill ‘Romeo and Juliet’ (1895) and the private Hillside School (1902), he began to build his own studio, house and farm, called ‘Taliesin I’, which meant a break with the past in emotional, social and professional terms and the beginning of a new architectural stage in the course of his career.

Rizzoli Publishing, The Wasmuth Folios were reissued by Rizzoli Publishing.

Hardcover and dust jacket. Bilingual German/English. Pages 224. 38.50 x 25.00 cm

Undoubtedly a valuable resource for historians and architects.

The architect’s introduction and comments on each project are faithfully reproduced. A new prologue analyzes the recently discovered historical background of these folios and Wright’s intention to present them as a primer for a new American democratic architecture.

Taliesin

Wright named his summer home “Taliesin” in honor of his Welsh heritage. Tally-ESS-in means “bright front” in Welsh, and the building sits on the side of a hill, like a frontage.

“An idea is salvation through imagination.” F.Ll.W.

F. Ll. W. Imperial Hotel Lunch Service, 1925 / 1966

See https://onlybook.es/blog/wright-en-el-museo-meiji-mura/

“Architecture is the triumph of human imagination over matter, methods, and men, to put man in possession of his own world. It is at least the geometric pattern of things, of life, of the human and social world. It is at best that magical framework of reality we sometimes touch upon when we use the word order.” F. Ll. W.

Notas

10

Francisco Martínez Mindeguía.

11

«The Drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright» was the title of Arthur Drexler’s book. New York: Horizon Press, 1962. «Frank Lloyd Wright Drawings» was the title of the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that same year.

12

The photos were published in the Architectural Record, 23, 1908, and those that served as the basis for the Wasmouth plates were: Larking Building, p. 167, Central Space of the Larkin Building, p. 169, Larkin Building modified, p. 173, Dana House, p. 174, Hickox House, p. 179, Living Room of the Bradley House, p. 180, Tomek House, p. 187, Barton House, p. 206, and Unitarian House modified, p. 212.

13

Reporting by Barry Byrne. March 25, 1965.

14

H. Allen Brooks (1925–2010) was an architectural historian and professor at the University of Toronto.

He received his B.A. in 1950 from Dartmouth College, a M.A. in 1955 from Yale University, and a Ph.D. in 1957 from Northwestern University.

He has lectured in North America, Europe, and Australia.

The term «Prairie School» is attributed to Brooks.

He received the Wright Spirit Award, the highest award given by the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy.

He was president of the Society of Architectural Historians, a founding member of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, and a life member of the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain.

Brooks has written on Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School, as well as on the early years of Le Corbusier, published by the Toronto Press (1972/75, Cambridge 1981, Cooper-Hewitt Museum 1984, and for WW Norton 2006.

15

Polytechnic University of Catalonia. “The Wasmuth Portfolio of F. Ll. Wright 1910.” Master’s thesis. Architect Santiago Reinoso Ochoa. (2014/15).

16

María Rubio Giménez, University of Zaragoza. F.L. Wright and Japan. 2014/15.

17

Wright, F. Ll. 1932. Pp 196.

18

Nishi K y Hozumi K. (1985). Stanley-Baker J. (2000).

———————————————-

Arq. Hugo Alberto Kliczkowski Juritz

Onlybook.es/blog

Hugoklico.blogspot.com

Entradas

Entrada anteriorGB. Frank Lloyd Wright, some relevant stages of his life. Part 1. (MBgb)

Entrada siguiente GB. Frank Lloyd Wright, some relevant stages of his life. Part 2. (MBgb)